Il colore di una sospensione di nanogabbie dipende dallo spessore delle pareti delle gabbie e dalla dimensione dei pori in quelle pareti. come il loro colore, la loro capacità di assorbire la luce e convertirla in calore può essere controllata con precisione. Attestazione:WUSTL

In una conferenza che tenne nel 1906, il medico tedesco Paul Ehrlich coniò il termine Zuberkugel, o "proiettile magico, " come abbreviazione di un trattamento medico altamente mirato.

proiettili magici, chiamati anche proiettili d'argento, a causa della credenza folcloristica che solo i proiettili d'argento possano uccidere le creature soprannaturali, rimangono l'obiettivo degli sforzi di sviluppo dei farmaci oggi.

Un team di scienziati della Washington University di St. Louis sta attualmente lavorando su una bacchetta magica per il cancro, una malattia i cui trattamenti sono notoriamente indiscriminati e aspecifici. Ma i loro proiettili sono d'oro piuttosto che d'argento. Letteralmente.

I proiettili d'oro sono nanogabbie d'oro che, quando iniettato, accumularsi selettivamente nei tumori. Quando i tumori vengono successivamente immersi nella luce laser, il tessuto circostante è appena riscaldato, ma le nanogabbie convertono la luce in calore, uccidendo le cellule maligne.

In un articolo appena pubblicato sulla rivista Piccolo , il team descrive il successo del trattamento fototermico dei tumori nei topi.

La squadra include Younan Xia, dottorato di ricerca, il James M. McKelvey Professore di Ingegneria Biomedica presso la Scuola di Ingegneria e Scienze Applicate, Michael J. Welch, dottorato di ricerca, professore di radiologia e biologia dello sviluppo presso la Facoltà di Medicina, Jingy Chen, dottorato di ricerca, professore assistente di ricerca di ingegneria biomedica e Charles Glaus, dottorato di ricerca, assegnista di ricerca post-dottorato presso il Dipartimento di Radiologia.

"Abbiamo visto cambiamenti significativi nel metabolismo e nell'istologia del tumore, "dice Welch, "il che è notevole dato che il lavoro era esplorativo, la "dose" del laser non era stata massimizzata, e i tumori erano presi di mira "passivamente" piuttosto che "attivamente".

Le nanogabbie d'oro (a destra) sono scatole vuote realizzate facendo precipitare l'oro su nanocubi d'argento (a sinistra). L'argento si erode simultaneamente dall'interno del cubo, entrando nella soluzione attraverso i pori che si aprono negli angoli ritagliati del cubo. Attestazione:WUSTL

Perché le nanogabbie si surriscaldano?

Le nanogabbie stesse sono innocue. "Sali d'oro e colloidi d'oro sono stati usati per curare l'artrite per più di 100 anni, " dice Welch. "La gente sa cosa fa l'oro nel corpo ed è inerte, quindi speriamo che questo sia un approccio non tossico".

"La chiave per la terapia fototermica, "dice Xia, "è la capacità delle gabbie di assorbire efficacemente la luce e convertirla in calore."

Sospensioni delle nanogabbie d'oro, che hanno all'incirca le stesse dimensioni di una particella virale, non sono sempre gialli, come ci si aspetterebbe, ma invece può essere qualsiasi colore dell'arcobaleno.

Sono colorati da qualcosa chiamato risonanza plasmonica di superficie. Alcuni degli elettroni nell'oro non sono ancorati ai singoli atomi ma formano invece un gas di elettroni fluttuante, Xia spiega. La luce che cade su questi elettroni può farli oscillare all'unisono. Questa oscillazione collettiva, il plasmone di superficie, sceglie una particolare lunghezza d'onda, o colore, fuori dalla luce incidente, e questo determina il colore che vediamo.

Gli artigiani medievali realizzavano vetrate color rosso rubino mescolando cloruro d'oro in vetro fuso, un processo che ha lasciato minuscole particelle d'oro sospese nel vetro, dice Xia.

The resonance — and the color — can be tuned over a wide range of wavelengths by altering the thickness of the cages' walls. For biomedical applications, Xia's lab tunes the cages to 800 nanometers, a wavelength that falls in a window of tissue transparency that lies between 750 and 900 nanometers, in the near-infrared part of the spectrum.

Light in this sweet spot can penetrate as deep as several inches in the body (either from the skin or the interior of the gastrointestinal tract or other organ systems).

The conversion of light to heat arises from the same physical effect as the color. The resonance has two parts. At the resonant frequency, light is typically both scattered off the cages and absorbed by them.

By controlling the cages' size, Xia's lab tailors them to achieve maximum absorption.

Passive targeting

"If we put bare nanoparticles into your body, " says Xia, "proteins would deposit on the particles, and they would be captured by the immune system and dragged out of the bloodstream into the liver or spleen."

Per evitare ciò, the lab coated the nanocages with a layer of PEG, a nontoxic chemical most people have encountered in the form of the laxatives GoLyTELY or MiraLAX. PEG resists the adsorption of proteins, in effect disguising the nanoparticles so that the immune system cannot recognize them.

Instead of being swept from the bloodstream, the disguised particles circulate long enough to accumulate in tumors.

A growing tumor must develop its own blood supply to prevent its core from being starved of oxygen and nutrients. But tumor vessels are as aberrant as tumor cells. They have irregular diameters and abnormal branching patterns, but most importantly, they have thin, leaky walls.

The cells that line a tumor's blood vessel, normally packed so tightly they form a waterproof barrier, are disorganized and irregularly shaped, and there are gaps between them.

The nanocages infiltrate through those gaps efficiently enough that they turn the surface of the normally pinkish tumor black.

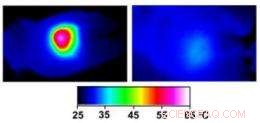

Infrared images made while tumors were irradiated with a laser show that in nanocage-injected mice (left), the surface of the tumor quickly became hot enough to kill cells. In buffer-injected mice (right), the temperature barely budged. This specificity is what makes photothermal therapy so attractive as a cancer therapy. Credit:WUSTL

A trial run

In Welch's lab, mice bearing tumors on both flanks were randomly divided into two groups. The mice in one group were injected with the PEG-coated nanocages and those in the other with buffer solution. Several days later the right tumor of each animal was exposed to a diode laser for 10 minutes.

The team employed several different noninvasive imaging techniques to follow the effects of the therapy. (Welch is head of the oncologic imaging research program at the Siteman Cancer Center of Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes-Jewish Hospital and has worked on imaging agents and techniques for many years.)

During irradiation, thermal images of the mice were made with an infrared camera. As is true of cells in other animals that automatically regulate their body temperature, mouse cells function optimally only if the mouse's body temperature remains between 36.5 and 37.5 degrees Celsius (98 to 101 degrees Fahrenheit).

At temperatures above 42 degrees Celsius (107 degrees Fahrenheit) the cells begin to die as the proteins whose proper functioning maintains them begin to unfold.

In the nanocage-injected mice, the skin surface temperature increased rapidly from 32 degrees Celsius to 54 degrees C (129 degrees F).

In the buffer-injected mice, però, the surface temperature remained below 37 degrees Celsius (98.6 degrees Fahrenheit).

To see what effect this heating had on the tumors, the mice were injected with a radioactive tracer incorporated in a molecule similar to glucose, the main energy source in the body. Positron emission and computerized tomography (PET and CT) scans were used to record the concentration of the glucose lookalike in body tissues; the higher the glucose uptake, the greater the metabolic activity.

The tumors of nanocage-injected mice were significantly fainter on the PET scans than those of buffer-injected mice, indicating that many tumor cells were no longer functioning.

The tumors in the nanocage-treated mice were later found to have marked histological signs of cellular damage.

Active targeting

The scientists have just received a five-year, $2, 129, 873 grant from the National Cancer Institute to continue their work with photothermal therapy.

Despite their results, Xia is dissatisfied with passive targeting. Although the tumors took up enough gold nanocages to give them a black cast, only 6 percent of the injected particles accumulated at the tumor site.

Xia would like that number to be closer to 40 percent so that fewer particles would have to be injected. He plans to attach tailor-made ligands to the nanocages that recognize and lock onto receptors on the surface of the tumor cells.

In addition to designing nanocages that actively target the tumor cells, the team is considering loading the hollow particles with a cancer-fighting drug, so that the tumor would be attacked on two fronts.

But the important achievement, from the point of view of cancer patients, is that any nanocage treatment would be narrowly targeted and thus avoid the side effects patients dread.

The TV and radio character the Lone Ranger used only silver bullets, allegedly to remind himself that life was precious and not to be lightly thrown away. If he still rode today, he might consider swapping silver for gold.