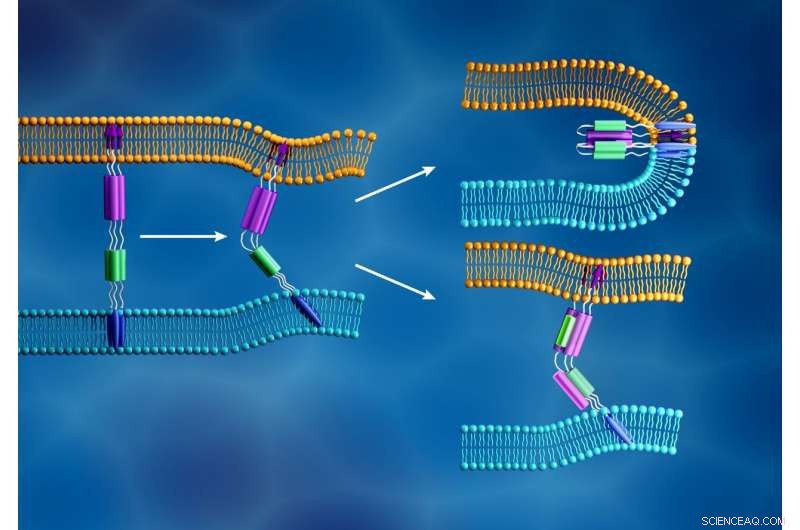

La nuova membrana del coronavirus (azzurro) e la membrana cellulare umana (arancione) si fondono quando il peptide di fusione della subunità S2 virale (frecce viola) si inserisce nella membrana cellulare e un diverso componente della subunità S2 (viola e verde) si piega per formare una struttura stretta, come mostrato in alto a destra. In contrasto, come illustrato in basso a destra, gli inibitori della fusione sono progettati per prevenire l'infezione virale interrompendo questo processo. Attestazione:ORNL/Jill Hemman

SARS-CoV-2, il coronavirus responsabile della malattia COVID-19, sta infettando il mondo a un ritmo rapido. Capire come funziona questa infezione a livello molecolare potrebbe aiutare gli esperti a scoprire modi per moderare o fermare la diffusione.

Un team di scienziati dell'Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) del Dipartimento dell'Energia (DOE) sta usando la riflettometria a neutroni per fare proprio questo.

I neutroni sono in grado di sondare i materiali biologici in condizioni fisiologiche senza danneggiarli. Sfruttando queste proprietà, i ricercatori possono misurare la dinamica dell'infezione del virus mentre accade.

La loro missione è dare uno sguardo dettagliato ad alcune delle prime fasi dell'infezione che si verificano sulla membrana cellulare. Questi risultati aiuteranno il team a testare i candidati farmaci antivirali che potrebbero interrompere questo processo. I dati ottenuti da questi esperimenti potrebbero anche informare altri studi incentrati sullo sviluppo di terapie e vaccini.

I ricercatori stanno concentrando la loro analisi sulle proteine spike di SARS-CoV-2, proteine strutturali simili a barbe che ricoprono la superficie del virus e innescano il processo di infezione. La proteina spike si lega a un recettore sullo strato esterno della cellula ospite e facilita la fusione tra le membrane virali e cellulari, permettendo al virus di entrare nella cellula e rilasciare il suo materiale genetico. Il macchinario per la produzione di proteine della cellula utilizza quindi queste informazioni genetiche per creare nuove copie del virus.

Quando SARS-CoV-2 dirotta una cellula ospite, la sua proteina spike si divide in due subunità, chiamati S1 e S2. Le due parti sono entrambe essenziali per l'infezione. La subunità S1 contiene un dominio di legame al recettore che riconosce e si aggancia a un recettore cellulare. I recettori cellulari sono proteine incorporate all'interno della membrana cellulare che possono legarsi a specifiche molecole al di fuori della cellula. Questa connessione può far cambiare forma ai componenti, che a sua volta potrebbe indurre cambiamenti a cascata all'interno della cellula. Per la proteina spike SARS-CoV-2, questa connessione attiva la subunità S2, che aiuta il virus a fondere la sua membrana con quella della cellula. Perciò, la funzione della proteina spike è simile all'apertura di una porta chiusa a chiave, con S1 come chiave che apre la porta e S2 come forza che apre la porta.

Imparare dalle epidemie del passato

La struttura complessiva della proteina spike SARS-CoV-2 è molto simile a quella di SARS-CoV, un precedente coronavirus che ha causato la sindrome respiratoria acuta grave (SARS), e questa somiglianza ha aiutato il team a sviluppare la propria strategia di ricerca.

La subunità S1 è al centro di molti studi sullo sviluppo di farmaci, poiché è stato dimostrato che questa parte della proteina spike provoca una risposta immunitaria nel corpo umano. Però, precedenti studi SARS-CoV hanno rilevato che la subunità S1 presenta alti tassi di mutazione, permettendo al virus di eludere i trattamenti a base di anticorpi pur mantenendo la sua capacità di infettare le cellule. "Questa è la lezione che abbiamo imparato dall'epidemia di SARS originale, " disse Minh Phan, un associato di ricerca post-dottorato presso ORNL e ricercatore principale di questo progetto.

Phan e i suoi colleghi stanno studiando la subunità S2 perché questo componente della proteina spike non muta così rapidamente. I trattamenti che si dimostrano efficaci nell'inibire la funzione S2 possono rimanere efficaci più a lungo.

Una visione su scala nanometrica del coronavirus

Per comprendere meglio la dinamica delle subunità virali S2 e delle membrane delle cellule ospiti, i ricercatori stanno impiegando il riflettometro per liquidi (LIQREF) presso la Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) dell'ORNL. Misurando come i neutroni si riflettono ad angoli diversi quando passano attraverso diversi tipi di materia, lo strumento può aiutare a far luce sulla struttura dei materiali biologici su scala molecolare.

Il team ha prima sintetizzato una membrana lipidica che imita la membrana esterna delle cellule che rivestono le superfici all'interno dei polmoni umani, dove può avvenire questa infezione virale. Hanno identificato come i lipidi erano organizzati all'interno della membrana e come questa disposizione cambia quando le membrane sono esposte a condizioni diverse, come la temperatura, pressione, e acidità.

Allo strumento LIQREF, i ricercatori hanno diffuso la membrana lipidica sopra un sottile strato d'acqua in un apparato chiamato Langmuir trogolo. Quindi introducono la subunità S2 a queste membrane per osservare in dettaglio come le membrane S2 e lipidiche cambiano forma quando interagiscono.

Anche i neutroni sono ideali per questo studio perché sono sensibili all'elemento idrogeno, comune a tutte le molecole biologiche, e i suoi isotopi. Sostituendo alcuni atomi di idrogeno con atomi di deuterio, gli scienziati possono creare contrasto nei loro campioni e concentrarsi selettivamente su diverse caratteristiche strutturali. Questa tecnica è utile per studiare campioni che coinvolgono più componenti con densità simili, come le membrane lipidiche.

"In genere, queste membrane non sono membrane monolipidiche, "ha detto John Ankner, uno scienziato dello strumento coinvolto in questo studio. "Sono costituiti da lipidi di una certa struttura, lipids of another structure, cholesterol, proteine, and things that come in contact with them."

To capture this complexity, the research team is investigating multiple versions of the membrane, changing the contrast of the sample with deuterium each time.

Researchers at ORNL are using neutron scattering at the Spallation Neutron Source to better understand how spike proteins help the COVID-19 virus infect human cells and what drugs could be effective in stopping them. This research team includes John Ankner (left) and Minh Phan (right). Attestazione:ORNL/Genevieve Martin

"By taking multiple measurements and assembling all of this information together, you can create a single picture of how these different components go together, " said Ankner.

The information derived from these experiments will then help steer the team's efforts in selecting and testing drug candidates that could block this interaction, such as fusion inhibitors that successfully blocked original SARS-CoV infections. If these inhibitors can stop the new coronavirus from invading healthy cells, existing drugs could potentially be repurposed to treat COVID-19 patients. The results may also help guide the design of new fusion inhibitors.

Capturing infection

While other studies have used protein crystallography to better understand the atomic structure of the coronavirus S2 subunit alone, this project is analyzing how S2 changes shape when interacting with a lipid membrane. A shape change could be important for inducing actions within a cell after the spike S1 subunit binds to the cell receptor. Phan also notes that the LIQREF instrument allows the team to measure these dynamics under physiological conditions, whereas protein crystallography only allows researchers to capture what the S2 subunit looks like in a crystallized form.

"At ORNL, we have the right tools to study the dynamics of the interaction under physiological conditions. This allows us to better understand how the S2 subunit moves and changes shape naturally in a wet environment, " said Phan. "Such information could complement what experts already know about the protein from crystallography. If we can help verify what this mechanism looks like, then we may have a clearer understanding to guide the development of drugs that block the fusion process.

Collaboration is key

Certo, learning more about the S2 subunit and its certain behaviors depends on the ability to grow quality samples, which involves synthesizing S2 subunit proteins, purifying them, and preparing them for experimentation.

Phan and Ankner note that this part of their research has been made possible only through collaboration with labs across ORNL and at outside institutions.

The S2 subunit protein was synthesized in mammalian cell cultures by Steve Foster, a biomedical researcher at the University of Tennessee Medical Center in Knoxville, Tennessee. Through this method, he can develop S2 proteins for research that retain several aspects of its natural structure and function.

"In our lab we routinely use mammalian cell cultures for protein production, so we hope we've produced an S2 protein best suited for this research analysis. Our proximity to ORNL also works well in that the sample doesn't have to travel far, meaning less risk of damaging the protein or distorting its original structure, which is critical for this work, " said Foster.

Following its synthesis, the sample was purified by Jessy Labbé and Michael Melesse Vergara from ORNL's Biosciences Division. Scientists from the ORNL Neutron Sciences Directorate then performed a series of tests to confirm the structure of the sample protein and check its purity. This effort was implemented by Yichong Fan and Wellington Leite from the Bio-Labs team, and Jacob Kinnun and Mary Odom from the SNS team.

"We put an enormous effort into making sure the protein has the right properties going into the experiment. If it does not, we could get spurious results and misinterpret what we're doing, " said Hugh O'Neill, director of ORNL's Center for Structural and Molecular Biology and lead researcher for the Bio-Labs team.

"This virus is extremely delicate in its components, and it's a big challenge to get these materials to the neutron instrument, " said Ankner. "That's why involving various ORNL labs and the University of Tennessee is so crucial. Each step that eventually gets the sample onto our instrument requires the expertise of lots of people."

This project also relied on efforts from the LIQREF instrument staff, who were instrumental in developing the systems, protocols, and modeling frameworks necessary to run the experiments and interpret the data.

"Experts across the division, across ORNL, and from partner institutes have come together for this project, " said Phan. "We couldn't have done this without their support, and it's greater motivation to fulfill our mission."