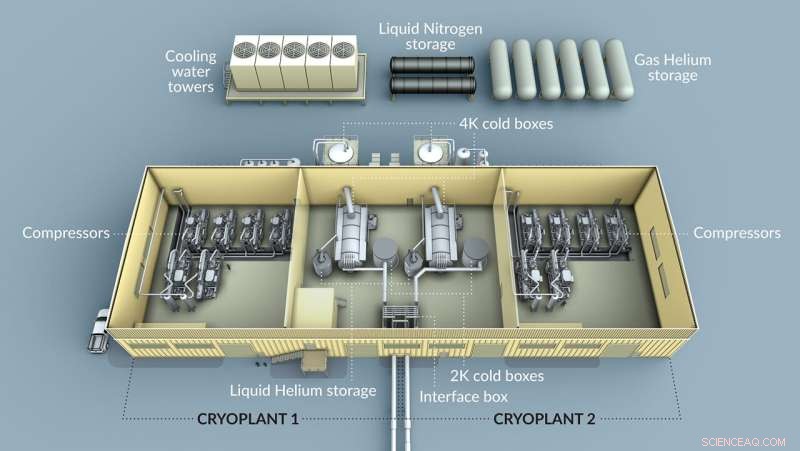

Uno schema della criopianta LCLS-II. Credito:Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Oggi ci vuole solo un'ora e mezza per rendere un acceleratore di particelle superconduttore presso lo SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory del Dipartimento dell'Energia più freddo dello spazio esterno.

"Ora fai clic su un pulsante e la macchina passa da 4,5 Kelvin a 2 Kelvin", ha affermato Eric Fauve, direttore del team criogenico di SLAC.

Sebbene il processo sia ora completamente automatizzato, per portare questo acceleratore, chiamato LCLS-II, a 2 Kelvin, o meno 456 gradi Fahrenheit, ci sono voluti sei anni di progettazione, costruzione, installazione e avvio di un sistema complesso.

L'originale LCLS, o Linac Coherent Light Source, accelera gli elettroni per produrre infine i raggi X utilizzati negli esperimenti di sondaggio di atomi e molecole. LCLS-II funzionerà contemporaneamente a LCLS. Tuttavia, a differenza di LCLS, che utilizza parti in rame a temperatura ambiente per accelerare gli elettroni, l'aggiornamento LCLS-II impiega criomoduli superconduttori. Questi criomoduli impartiscono elettroni con energia in modo più efficiente, il che aiuterà a generare impulsi di raggi X più potenti per espandere le possibilità sperimentali attraverso i campi.

Ma, mentre LCLS può funzionare a temperatura ambiente, LCLS-II deve essere raffreddato a 2 Kelvin, appena 4 gradi Fahrenheit sopra lo zero assoluto, per diventare superconduttore.

E questo significava che SLAC aveva bisogno di una squadra per concentrarsi sulle cose fredde.

Assemblare una squadra per assemblare un crioimpianto

Prima che l'LCLS-II si raffreddasse, allo SLAC non c'era nessun gruppo dedito alla criogenia.

"La nostra più grande sfida è stata che questa era la prima volta che lo facevamo con un nuovo team", ha detto Fauve.

Il team criogenico LCLS-II, ora composto da 20 operatori e ingegneri, si è formato nel 2016 presso lo SLAC per costruire l'impianto che raffredda l'acceleratore:un impianto criogenico.

"Questo è un sistema complicato con molti sottosistemi che funzionano in tandem", ha affermato Viswanath Ravindranath, ingegnere di processo criogenico capo per LCLS-II.

SLAC ha lavorato a stretto contatto con gli ingegneri del Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory del DOE e della Jefferson National Accelerator Facility, nonché con aziende criogeniche leader nella progettazione e nell'acquisto di materiali per il crioimpianto.

"Questa collaborazione ha consentito al progetto LCLS-II di beneficiare delle migliori risorse criogeniche all'interno dei laboratori DOE e altrove", ha affermato Fauve.

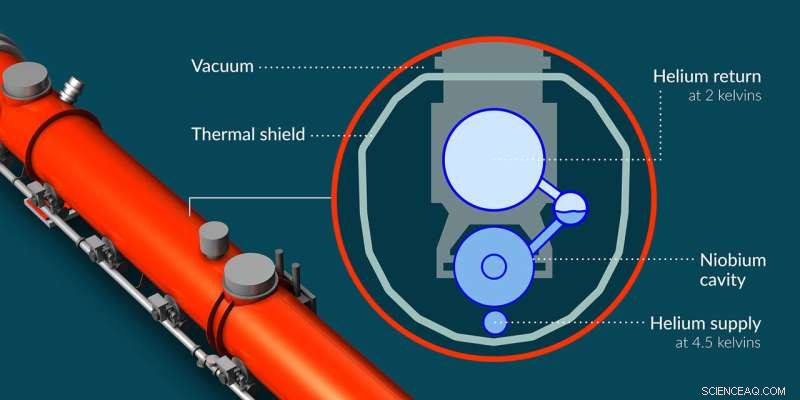

Una sezione trasversale dell'acceleratore LCLS-II che mostra dove fluiscono elio liquido e gassoso dentro e fuori il sistema. Credito:Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Il crioimpianto viene riempito con elio, che viene raffreddato e quindi pompato a LCLS-II. Mentre ogni altro elemento si congela al di sotto di 4 Kelvin, l'elio può rimanere un fluido e a 2 Kelvin l'elio diventa superfluido, il che significa che scorre senza viscosità. Questo fatto, e la capacità dell'elio superfluido di condurre il calore meglio di qualsiasi altra sostanza conosciuta, lo rendono il refrigerante perfetto per raffreddare un acceleratore superconduttore.

Prima che inizi il raffreddamento, i rimorchi accatastati con serbatoi a forma di hot dog forniscono elio gassoso a temperatura ambiente (circa 300 Kelvin) ai serbatoi di stoccaggio all'aperto del crioimpianto. La criopianta richiede un totale di quattro tonnellate di elio.

Ma questo elio arriva impuro. Eventuali impurità finiranno per congelare e intasare il sistema, quindi prima i depuratori devono intrappolare l'umidità o i gas indesiderati, come l'azoto, per ottenere il 99,999% di elio.

Dopo la purificazione, i compressori aumentano la pressione dell'elio. The pressure and temperature of a gas are coupled:as pressure decreases, temperature also decreases. So, while helpful later, this incidentally raises helium's temperature to 370 Kelvin.

Following compression, five large towers containing cooling water are used to lower helium's temperature back down to 300 Kelvin. The gas then enters the cryoplant's 4K cold box, which is a giant, uber-complicated helium refrigerator.

In the cold box, liquid nitrogen running 77 Kelvin knocks the helium down from 300 Kelvin to 80 Kelvin in a heat exchanger. In this device, the warm helium gas and colder liquid nitrogen travel in opposite directions while separated by a thin metal plate, transferring heat through the plate from the helium to the nitrogen. The plant uses 20 metric tons of liquid nitrogen every other day.

The helium then runs through a set of four turboexpanders. Now the initial gas-compressing step pays off:the turboexpanders expand the high-pressure gas, lowering its pressure enough to bring the helium all the way to 5.5 Kelvin.

However, the helium has more expanding to do before it can leave the cold box. It travels through a valve that has lower pressure on the other side. This lower pressure causes the gas to expand, lowering its pressure and bringing its temperature down to 4.5 Kelvin (hence the name of the 4K cold box), where it becomes a liquid.

This liquid helium is then sent through pipes to the accelerator's cryomodules, where it cools the machine to 4.5 Kelvin.

Once the 4K cold box was up and running, it took the Cryogenic team one week to cool LCLS-II from room temperature to 4.5 Kelvin, which it reached for the first time on March 28, 2022. But that's not cold enough!

Colder still

To reach 2 Kelvin, the 4.5 Kelvin helium undergoes yet another (final) expansion through a valve in the accelerator's cryomodules. Again, the lower pressure on the other side of the valve causes helium's pressure to drop. This cools helium to the goal temperature of 2 Kelvin.

Creating the low pressure inside the cryomodule is a feat in itself.

"The magic happens when it goes through that valve, but only because we have a train of cold compressors that maintains the pressure in the cryomodule at very low pressure," Fauve said. This set of five compressors stationed after the valve create the pivotal pressure difference on either side of the valve.

After months of turning on and configuring this cooling system, LCLS-II finally reached 2 Kelvin on April 15.

"Everything was possible because of all the hard work over the years from so many smart and dedicated people," said Swapnil Shrishrimal, cryogenic process and controls engineer for LCLS-II. "Being a small team, as well as a young team, we are very proud of the system we commissioned."

When the electron beam is on and being accelerated by the cryomodules, the 2 Kelvin helium will absorb heat from the accelerator, boil, and turn back into gas. That gas is injected back into the 4K cold box to help cool warmer helium.

"We don't want to waste the cooling capacity, so we try to recover as much of it as possible," Ravindranath said. The system recycles the helium, which is expensive, although essential for long-term operation.

The Cryogenic team actually built two cryoplants, which share a building, but LCLS-II only uses one. The second cryoplant will support planned upgrades to LCLS-II. When both cryoplants are on they will use approximately 10 megawatts of electrical power.

Only four other cryoplants in the United States cool this much helium to 2 Kelvin. Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility and Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, which both house cryoplants of similar magnitude, supported SLAC's design and procurement of equipment. SLAC collaborated with Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Brookhaven National Laboratory, and CERN as well.

"The years of expertise and support of our partner labs allowed us to do this," Shrishrimal said. Fauve also credits the team's success to their extensive planning and dedication. The entire Cryogenic team stayed on site during the pandemic to continue bringing the plant to life.

"Even when SLAC was shut down, if you were at the cryoplant you would not be able to tell the difference before and during COVID," Fauve said, except for the masks and social distancing, of course.

LCLS-II is expected to produce its first X-rays early next year. The Cryogenic team feels confident they will continue to run their very complicated refrigerator with ease.

"It's a pretty nice and easy operation now because everything is automated," Shrishrimal said. + Esplora ulteriormente