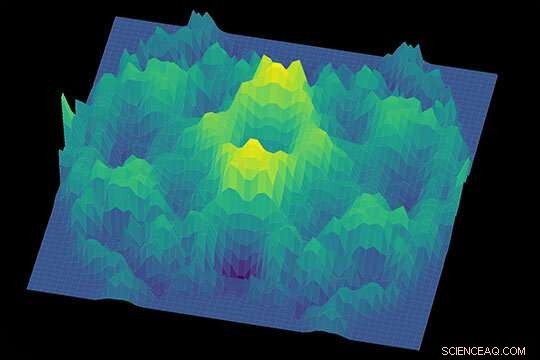

Una rappresentazione 3D del continuum spin-eccitazione, un possibile segno distintivo di un liquido di spin quantistico, osservata nel 2019 in un campione di cristallo singolo di pirocloro di cerio e zirconio. Credito:Tong Chen/Rice University

Il lavoro investigativo computazionale di fisici statunitensi e tedeschi ha confermato che il pirocloro di cerio e zirconio è un liquido di spin quantico 3D.

Nonostante il nome, i liquidi di spin quantico sono materiali solidi in cui l'entanglement quantistico e la disposizione geometrica degli atomi frustrano la naturale tendenza degli elettroni a ordinarsi magneticamente l'uno rispetto all'altro. La frustrazione geometrica in un liquido di spin quantistico è così grave che gli elettroni fluttuano tra gli stati magnetici quantistici, non importa quanto freddi diventino.

I fisici teorici lavorano regolarmente con modelli di meccanica quantistica che manifestano liquidi di spin quantistico, ma trovare prove convincenti della loro esistenza in materiali fisici reali è stata una sfida lunga decenni. Mentre un certo numero di materiali 2D o 3D sono stati proposti come possibili liquidi di spin quantistico, il fisico della Rice University Andriy Nevidomskyy ha affermato che non esiste un consenso stabilito tra i fisici sul fatto che qualcuno di loro si qualifichi.

Nevidomskyy spera che cambierà in base alle indagini computazionali che lui e i colleghi della Rice, della Florida State University e del Max Planck Institute for Physics of Complex Systems di Dresda, in Germania, hanno pubblicato questo mese sulla rivista ad accesso aperto npj Quantum Materials .

"Sulla base di tutte le prove che abbiamo oggi, questo lavoro conferma che i singoli cristalli del pirocloro di cerio identificati come liquidi di spin quantico 3D candidati nel 2019 sono effettivamente liquidi di spin quantistico con eccitazioni di spin frazionate", ha affermato.

La proprietà intrinseca degli elettroni che porta al magnetismo è lo spin. Ogni elettrone si comporta come una minuscola barra magnetica con un polo nord e uno sud e, quando misurato, gli spin dei singoli elettroni puntano sempre verso l'alto o verso il basso. Nella maggior parte dei materiali di uso quotidiano, le rotazioni puntano verso l'alto o verso il basso a caso. Ma gli elettroni sono di natura antisociale e questo può indurli a organizzare i loro giri in relazione ai loro vicini in alcune circostanze. Nei magneti, ad esempio, gli spin sono disposti collettivamente nella stessa direzione e negli antiferromagneti sono disposti secondo uno schema up-down, up-down.

A temperature molto basse, gli effetti quantistici diventano più importanti e questo fa sì che gli elettroni organizzino i loro giri collettivamente nella maggior parte dei materiali, anche quelli in cui gli spin punterebbero in direzioni casuali a temperatura ambiente. Quantum spin liquids are a counterexample, where spins do not point in a definite direction—even up or down—no matter how cold the material becomes.

"A quantum spin liquid, by its very nature, is an example of a fractionalized state of matter," said Nevidomskyy, associate professor of physics and astronomy and a member of both the Rice Quantum Initiative and the Rice Center for Quantum Materials (RCQM). "The individual excitations are not spin flips from up to down or vice versa. They're these bizarre, delocalized objects that carry half of one spin degree of freedom. It's like half of a spin."

Nevidomskyy was part of the 2019 study led by Rice experimental physicist Pengcheng Dai that found the first evidence that cerium zirconium pyrochlore was a quantum spin liquid. The team's samples were the first of their kind:Pyrochlores because of their 2-to-2-to-7 ratio of cerium, zirconium and oxygen, and single crystals because the atoms inside were arranged in a continuous, unbroken lattice. Inelastic neutron scattering experiments by Dai and colleagues revealed a quantum spin liquid hallmark, a continuum of spin excitations measured at temperatures as low as 35 millikelvin.

"You could argue that they found the suspect and charged him with the crime," Nevidomskyy said. "Our job in this new study was to prove to the jury that the suspect is guilty."

Nevidomskyy and colleagues built their case using state-of-the-art Monte Carlo methods, exact diagonalization as well as analytical tools to perform the spin dynamics calculations for an existing quantum mechanical model of cerium zirconium pyrochlore. The study was conceived by Nevidomskyy and Max Planck's Roderich Moessner, and the Monte Carlo simulations were performed by Florida State's Anish Bhardwaj and Hitesh Changlani, with contributions from Rice's Han Yan and Max Planck's Shu Zhang.

"The framework for this theory was known, but the exact parameters, of which there are at least four, were not," Nevidomskyy said. "In different compounds, these parameters could have different values. Our goal was to find those values for cerium pyrochlore and determine whether they describe a quantum spin liquid."

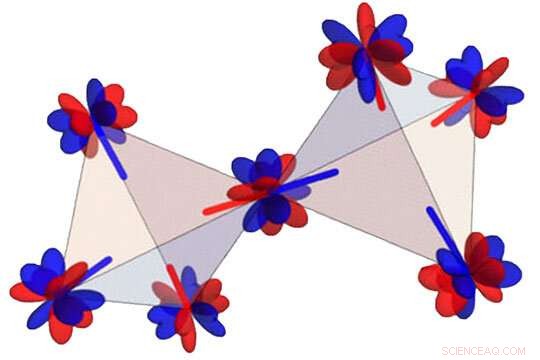

U.S. and German physicists found evidence that cerium zirconium pyrochlore crystals are “octupolar quantum spin liquids” in which octupolar magnetic moments (red and blue) contribute to fractionalized magnetism. Credit:A. Nevidomskyy/Rice University

"It would be like a ballistics expert who is using Newton's second law to calculate a bullet's trajectory," he said. "Newton's law is known, but it only has predictive power if you supply the initial conditions like the bullet's mass and initial velocity. Those initial conditions are analogous to these parameters. We had to reverse engineer, or sleuth out, 'What are those initial conditions inside this cerium material?' and, 'Does that match the prediction of this quantum spin liquid?'"

To build a convincing case, the researchers tested the model against thermodynamic, neutron-scattering and magnetization results from previously published experimental studies of cerium zirconium pyrochlore.

"If you just have one piece of evidence, you might inadvertently find several models that still fit the description," Nevidomskyy said. "We actually matched not one, but three different pieces of evidence. So, a single candidate had to match all three experiments."

Some studies have implicated the same type of quantum magnetic fluctuations that arise in quantum spin liquids as a possible cause for unconventional superconductivity . But Nevidomskyy said the computational findings are primarily of fundamental interest to physicists.

"This satisfies our innate desire, as physicists, to find out how nature works," he said. "There's no application I know of that might benefit. It's not immediately tied to quantum computing, although ideas exist for using fractionalized excitations as a platform for logical qubits."

He said one particularly interesting point for physicists is the deep connection between quantum spin liquids and the experimental realization of magnetic monopoles, theoretical particles whose potential existence is still debated by cosmologists and high-energy physicists.

"When people talk about fractionalization, what they mean is the system behaves as if a physical particle, like an electron, splits into two halves that kind of wander around and then recombine somewhere later," Nevidomskyy said. "And in pyrochlore magnets such as the one we studied, these wandering objects moreover behave like quantum magnetic monopoles."

Magnetic monopoles can be visualized as isolated magnetic poles like either the upward or downward facing pole of a single electron.

"Of course, in classical physics one can never isolate just one end of a bar magnet," he said. "The north and south monopoles always come in pairs. But in quantum physics, magnetic monopoles can hypothetically exist, and quantum theorists constructed these almost 100 years ago to explore fundamental questions about quantum mechanics.

"As far as we know, magnetic monopoles don't exist in a raw form in our universe," Nevidomskyy said. "But it turns out that a fancy version of monopoles does exist in these cerium pyrochlore quantum spin liquids. A single spin flip creates two fractionalized quasiparticles called spinons that behave like monopoles and wander around the crystal lattice."

The study also found evidence that monopole-like spinons were created in an unusual way in cerium zirconium pyrochlore. Due to the tetrahedral arrangement of magnetic atoms in the pyrochlore, the study suggests they develop octupolar magnetic moments—spin-like magnetic quasiparticles with eight poles—at low temperatures. The research showed spinons in the material were produced from both these octupolar sources and more conventional, dipolar spin moments.

"Our modeling established the exact proportions of interactions of these two components with one another," Nevidomskyy said. "It opens a new chapter in the theoretical understanding of not only the cerium pyrochlore materials but of octupolar quantum spin liquids in general." + Esplora ulteriormente