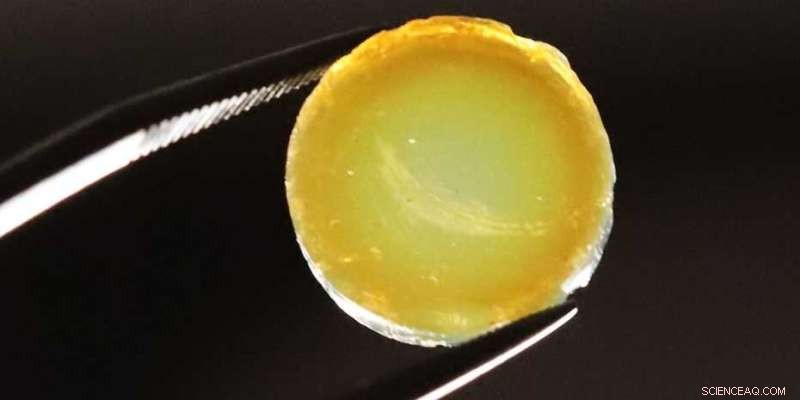

Un aerogel a forma di compressa composto da nanoparticelle di palladio e TiO2 drogate con azoto. Credito:Markus Niederberger / ETH Zurigo

Gli aerogel sono materiali straordinari che hanno stabilito Guinness World Records più di una dozzina di volte, anche come i solidi più leggeri del mondo.

Il professor Markus Niederberger del Laboratorio per i materiali multifunzionali dell'ETH di Zurigo lavora da tempo con questi materiali speciali. Il suo laboratorio è specializzato in aerogel composti da nanoparticelle semiconduttrici cristalline. "Siamo l'unico gruppo al mondo in grado di produrre questo tipo di aerogel con una qualità così elevata", afferma.

Un uso degli aerogel a base di nanoparticelle è come fotocatalizzatori. Questi vengono utilizzati ogni volta che una reazione chimica deve essere abilitata o accelerata con l'aiuto della luce solare, un esempio è la produzione di idrogeno.

Il materiale preferito per i fotocatalizzatori è il biossido di titanio (TiO2 ), un semiconduttore. Ma TiO2 ha un grosso svantaggio:può assorbire solo la parte UV della luce solare, solo circa il 5% dello spettro. Affinché la fotocatalisi sia efficiente e utile dal punto di vista industriale, il catalizzatore deve essere in grado di utilizzare una gamma più ampia di lunghezze d'onda.

Ampliare lo spettro con il doping dell'azoto

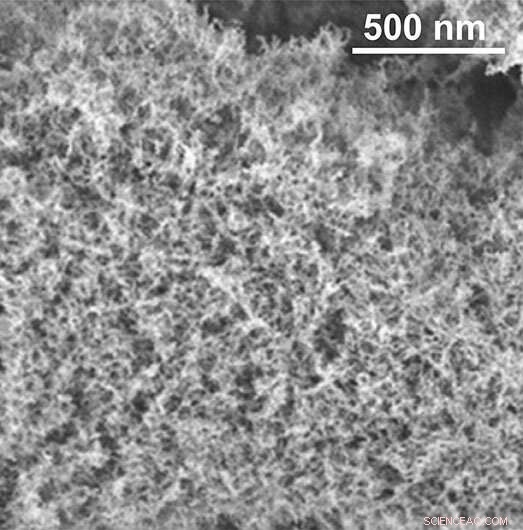

Ecco perché Junggou Kwon, dottorando di Niederberger, ha cercato un nuovo modo per ottimizzare un aerogel a base di TiO2 nanoparticelle. E ha avuto un'idea brillante:se il TiO2 L'aerogel di nanoparticelle viene "drogato" (per usare il termine tecnico) con azoto, in modo tale che i singoli atomi di ossigeno nel materiale siano sostituiti da atomi di azoto, l'aerogel può quindi assorbire ulteriori porzioni visibili dello spettro. Il processo di drogaggio lascia intatta la struttura porosa dell'aerogel. Lo studio su questo metodo è stato recentemente pubblicato sulla rivista Applied Materials &Interfaces .

Kwon ha prodotto per la prima volta l'aerogel usando TiO2 nanoparticelle e piccole quantità del metallo nobile palladio, che svolge un ruolo chiave nella produzione fotocatalitica dell'idrogeno. Ha quindi posizionato l'aerogel in un reattore e lo ha infuso con gas di ammoniaca. Ciò ha causato l'incorporazione di singoli atomi di azoto nella struttura cristallina del TiO2 nanoparticelle.

La struttura interna spugnosa dell'aerogel. Credito:Laboratorio per materiali multifunzionali / ETH Zurigo

L'aerogel modificato rende la reazione più efficiente

To test whether an aerogel modified in this way actually increases the efficiency of a desired chemical reaction—in this case, the production of hydrogen from methanol and water—Kwon developed a special reactor into which she directly placed the aerogel monolith. She then introduced a vapor of water and methanol to the aerogel in the reactor before irradiating it with two LED lights. The gaseous mixture diffuses through the aerogel's pores, where it is converted into the desired hydrogen on the surface of the TiO2 and palladium nanoparticles.

Kwon stopped the experiment after five days, but up to that point, the reaction was stable and proceeded continuously in the test system. "The process would probably have been stable for longer," Niederberger says. "Especially with regard to industrial applications, it's important for it to be stable for as long as possible." The researchers were satisfied with the reaction's results as well. Adding the noble metal palladium significantly increased the conversion efficiency:using aerogels with palladium produced up to 70 times more hydrogen than using those without.

Increasing the gas flow

This experiment served the researchers primarily as a feasibility study. As a new class of photocatalysts, aerogels offer an exceptional three-dimensional structure and offer potential for many other interesting gas-phase reactions in addition to hydrogen production. Compared to the electrolysis commonly used today, photocatalysts have the advantage that they could be used to produce hydrogen using only light rather than electricity.

Whether the aerogel developed by Niederberger's group will ever be used on a large scale is still uncertain. For example, there is still a question of how to accelerate the gas flow through the aerogel; at the moment, the extremely small pores hinder the gas flow too much. "To operate such a system on an industrial scale, we first have to increase the gas flow and also improve the irradiation of the aerogels," Niederberger says. He and his group are already working on these issues.

Aerogels are exceptional materials. They are extremely light and porous, and boast a huge surface area:one gram of the material can have a surface area of up to 1,200 square meters. Due to their transparency, aerogels have the appearance of "frozen smoke." They are excellent thermal insulators and so are used in aerospace applications and, increasingly, in the thermal insulation of buildings as well. However, their manufacture still requires a huge amount of energy, so the materials are expensive. The first aerogel was produced from silica by the chemist Samuel Kistler in 1931. + Esplora ulteriormente