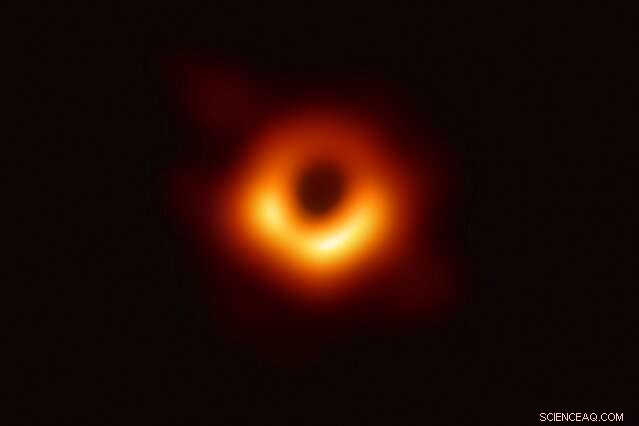

L'Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) - una serie su scala planetaria di otto radiotelescopi terrestri forgiata attraverso una collaborazione internazionale - è stata progettata per catturare immagini di un buco nero. In conferenze stampa coordinate in tutto il mondo, I ricercatori dell'EHT hanno rivelato di esserci riusciti, svelando la prima prova visiva diretta del buco nero supermassiccio al centro di Messier 87 e della sua ombra. Credito:Collaborazione EHT

Un team internazionale di oltre 200 astronomi, inclusi scienziati dell'Osservatorio Haystack del MIT, ha catturato le prime immagini dirette di un buco nero. Hanno compiuto questa straordinaria impresa coordinando la potenza di otto importanti osservatori radiofonici in quattro continenti, lavorare insieme come un virtuale, Telescopio delle dimensioni della Terra.

In una serie di articoli pubblicati oggi in un numero speciale di Lettere per riviste astrofisiche , il team ha rivelato quattro immagini del buco nero supermassiccio nel cuore di Messier 87, o M87, una galassia all'interno dell'ammasso di galassie della Vergine, 55 milioni di anni luce dalla Terra.

Tutte e quattro le immagini mostrano una regione scura centrale circondata da un anello di luce che appare sbilenco, più luminoso da un lato rispetto all'altro.

Albert Einstein, nella sua teoria della relatività generale, predisse l'esistenza di buchi neri, sotto forma di infinitamente denso, regioni compatte nello spazio, dove la gravità è così estrema che niente, nemmeno luce, può sfuggire dall'interno. Per definizione, i buchi neri sono invisibili. Ma se un buco nero è circondato da materiale che emette luce come il plasma, Le equazioni di Einstein prevedono che parte di questo materiale dovrebbe creare un'"ombra, "o un contorno del buco nero e il suo confine, noto anche come orizzonte degli eventi.

Sulla base delle nuove immagini di M87, gli scienziati credono di vedere per la prima volta l'ombra di un buco nero, sotto forma di regione scura al centro di ogni immagine.

La relatività prevede che l'immenso campo gravitazionale farà piegare la luce attorno al buco nero, formando un anello luminoso intorno alla sua sagoma, e farà anche orbitare il materiale circostante intorno all'oggetto a una velocità prossima alla luce. Il luminoso, L'anello sbilenco nelle nuove immagini offre una conferma visiva di questi effetti:il materiale diretto verso il nostro punto di osservazione mentre ruota appare più luminoso dell'altro lato.

Da queste immagini, teorici e modellisti del team hanno determinato che il buco nero è circa 6,5 miliardi di volte più massiccio del nostro sole. Piccole differenze tra ciascuna delle quattro immagini suggeriscono che il materiale sfreccia intorno al buco nero alla velocità della luce.

"Questo buco nero è molto più grande dell'orbita di Nettuno, e Nettuno impiega 200 anni per girare intorno al sole, "dice Geoffrey Crew, un ricercatore presso l'Osservatorio Haystack. "Con il buco nero M87 così massiccio, un pianeta in orbita gli girerebbe intorno entro una settimana e viaggerebbe a una velocità prossima a quella della luce".

"Le persone tendono a vedere il cielo come qualcosa di statico, che le cose non cambiano nei cieli, o se lo fanno, è su scale temporali più lunghe di una vita umana, "dice Vincenzo Pesce, un ricercatore presso l'Osservatorio Haystack. "Ma quello che troviamo per M87 è, nei minimi dettagli che abbiamo, gli oggetti cambiano nella scala temporale dei giorni. Nel futuro, possiamo forse produrre filmati di queste fonti. Oggi vediamo i frame di partenza".

"Queste straordinarie nuove immagini del buco nero M87 dimostrano che Einstein aveva ragione ancora una volta, "dice Maria Zuber, Il vicepresidente del MIT per la ricerca e l'E.A. Griswold Professore di Geofisica presso il Dipartimento di Terra, Scienze dell'atmosfera e planetarie. "La scoperta è stata resa possibile dai progressi nei sistemi digitali in cui gli ingegneri di Haystack si sono distinti da tempo".

"La natura era gentile"

Le immagini sono state scattate dall'Event Horizon Telescope, o EHT, un array su scala planetaria composto da otto radiotelescopi, ciascuno in un telecomando, ambiente d'alta quota, comprese le vette delle Hawaii, la Sierra Nevada spagnola, il deserto cileno, e la calotta glaciale antartica.

In un dato giorno, ogni telescopio funziona in modo indipendente, osservando oggetti astrofisici che emettono deboli onde radio. Però, un buco nero è infinitamente più piccolo e più scuro di qualsiasi altra sorgente radio nel cielo. Per vederlo chiaramente, gli astronomi devono usare lunghezze d'onda molto corte, in questo caso, 1,3 millimetri—che può tagliare le nuvole di materiale tra un buco nero e la Terra.

Fare un'immagine di un buco nero richiede anche un ingrandimento, o "risoluzione angolare, " equivale a leggere un testo su un telefono a New York da un caffè all'aperto a Parigi. La risoluzione angolare di un telescopio aumenta con le dimensioni della sua parabola ricevente. Tuttavia, nemmeno i più grandi radiotelescopi sulla Terra sono abbastanza grandi da vedere un buco nero.

Ma quando più radiotelescopi, separati da distanze molto grandi, sono sincronizzati e focalizzati su un'unica fonte nel cielo, possono funzionare come una grande parabola radio, attraverso una tecnica nota come interferometria della linea di base molto lunga, o VLBI. La loro risoluzione angolare combinata di conseguenza può essere notevolmente migliorata.

Per EHT, gli otto telescopi partecipanti riassunti in una parabola radio virtuale grande quanto la Terra, con la capacità di risolvere un oggetto fino a 20 microsecondi d'arco, circa 3 milioni di volte più nitido della visione 20/20. Per una felice coincidenza, si tratta della precisione necessaria per visualizzare un buco nero, secondo le equazioni di Einstein.

"La natura è stata gentile con noi, e ci ha dato qualcosa di abbastanza grande da vedere utilizzando attrezzature e tecniche all'avanguardia, "dice Equipaggio, co-leader del gruppo di lavoro sulla correlazione EHT e del team VLBI dell'Osservatorio ALMA.

"Gobbe di dati"

Il 5 aprile, 2017, l'EHT iniziò ad osservare M87. Dopo aver consultato numerose previsioni del tempo, gli astronomi hanno identificato quattro notti che avrebbero prodotto condizioni chiare per tutti e otto gli osservatori:una rara opportunità, durante il quale potevano funzionare come un piatto collettivo per osservare il buco nero.

Nella radioastronomia, i telescopi rilevano le onde radio, a frequenze che registrano i fotoni in arrivo come un'onda, con un'ampiezza e una fase misurate come tensione. Come hanno osservato M87, ogni telescopio riceveva flussi di dati sotto forma di voltaggi, rappresentati come numeri digitali.

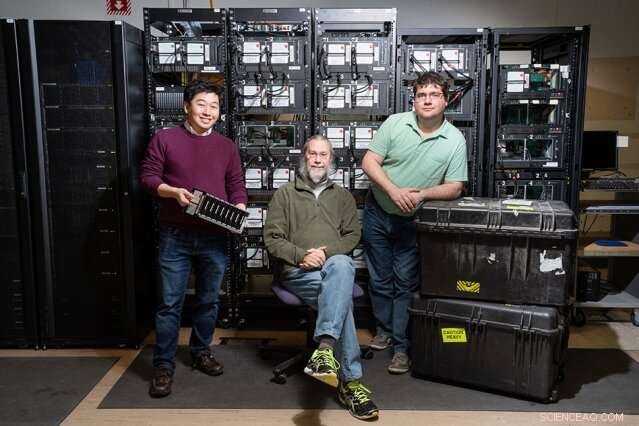

Il core team di scienziati Haystack che ha lavorato al progetto EHT si trova di fronte al correlatore dell'Haystack Observatory del MIT. Credito:Bryce Vickmark

"We're recording gobs of data—petabytes of data for each station, " Crew says.

In totale, each telescope took in about one petabyte of data, equal to 1 million gigabytes. Each station recorded this enormous influx that onto several Mark6 units—ultrafast data recorders that were originally developed at Haystack Observatory.

After the observing run ended, researchers at each station packed up the stack of hard drives and flew them via FedEx to Haystack Observatory, in Massachusetts, and Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, in Germania. (Air transport was much faster than transmitting the data electronically.) At both locations, the data were played back into a highly specialized supercomputer called a correlator, which processed the data two streams at a time.

As each telescope occupies a different location on the EHT's virtual radio dish, it has a slightly different view of the object of interest—in this case, M87. The data received by two separate telescopes may encode a similar signal of the black hole but also contain noise that's specific to the respective telescopes.

The correlator lines up data from every possible pair of the EHT's eight telescopes. From these comparisons, it mathematically weeds out the noise and picks out the black hole's signal. High-precision atomic clocks installed at every telescope time-stamp incoming data, enabling analysts to match up data streams after the fact.

"Precisely lining up the data streams and accounting for all kinds of subtle perturbations to the timing is one of the things that Haystack specializes in, " says Colin Lonsdale, Haystack director and vice chair of the EHT directing board.

Teams at both Haystack and Max Planck then began the painstaking process of "correlating" the data, identifying a range of problems at the different telescopes, fixing them, and rerunning the correlation, until the data could be rigorously verified. Only then were the data released to four separate teams around the world, each tasked with generating an image from the data using independent techniques.

"It was the second week of June, and I remember I didn't sleep the night before the data was released, to be sure I was prepared, " says Kazunori Akiyama, co-leader of the EHT imaging group and a postdoc working at Haystack.

All four imaging teams previously tested their algorithms on other astrophysical objects, making sure that their techniques would produce an accurate visual representation of the radio data. When the files were released, Akiyama and his colleagues immediately ran the data through their respective algorithms. È importante sottolineare che each team did so independently of the others, to avoid any group bias in the results.

"The first image our group produced was slightly messy, but we saw this ring-like emission, and I was so excited at that moment, " Akiyama remembers. "But simultaneously I was worried that maybe I was the only person getting that black hole image."

His concern was short-lived. Soon afterward all four teams met at the Black Hole Initiative at Harvard University to compare images, e trovato, with some relief, and much cheering and applause, that they all produced the same, lopsided, ring-like structure—the first direct images of a black hole.

"There have been ways to find signatures of black holes in astronomy, but this is the first time anyone's ever taken a picture of one, " Crew says. "This is a watershed moment."

"A new era"

The idea for the EHT was conceived in the early 2000s by Sheperd Doeleman Ph.D. '95, who was leading a pioneering VLBI program at Haystack Observatory and now directs the EHT project as an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Al tempo, Haystack engineers were developing the digital back-ends, recorders, and correlator that could process the enormous datastreams that an array of disparate telescopes would receive.

"The concept of imaging a black hole has been around for decades, " Lonsdale says. "But it was really the development of modern digital systems that got people thinking about radio astronomy as a way of actually doing it. More telescopes on mountaintops were being built, and the realization gradually came along that, Hey, [imaging a black hole] isn't absolutely crazy."

Nel 2007, Doeleman's team put the EHT concept to the test, installing Haystack's recorders on three widely scattered radio telescopes and aiming them together at Sagittarius A*, the black hole at the center of our own galaxy.

"We didn't have enough dishes to make an image, " recalls Fish, co-leader of the EHT science operations working group. "But we could see there was something there that's about the right size."

Oggi, the EHT has grown to an array of 11 observatories:ALMA, APEX, the Greenland Telescope, the IRAM 30-meter Telescope, the IRAM NOEMA Observatory, the Kitt Peak Telescope, the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, the Large Millimeter Telescope Alfonso Serrano, the Submillimeter Array, the Submillimeter Telescope, and the South Pole Telescope.

Coordinating observations and analysis has involved over 200 scientists from around the world who make up the EHT collaboration, with 13 main institutions, including Haystack Observatory. Key funding was provided by the National Science Foundation, the European Research Council, and funding agencies in East Asia, including the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. The telescopes contributing to this result were ALMA, APEX, the IRAM 30-meter telescope, the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, the Large Millimeter Telescope Alfonso Serrano, the Submillimeter Array, the Submillimeter Telescope, and the South Pole Telescope.

More observatories are scheduled to join the EHT array, to sharpen the image of M87 as well as attempt to see through the dense material that lies between Earth and the center of our own galaxy, to the heart of Sagittarius A*.

"We've demonstrated that the EHT is the observatory to see a black hole on an event horizon scale, " Akiyama says. "This is the dawn of a new era of black hole astrophysics."

Questa storia è stata ripubblicata per gentile concessione di MIT News (web.mit.edu/newsoffice/), un popolare sito che copre notizie sulla ricerca del MIT, innovazione e didattica.