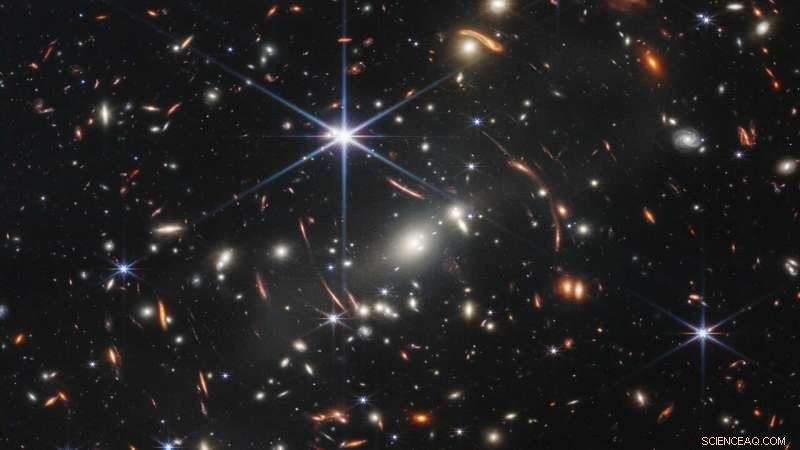

Questa immagine, la prima rilasciata dal telescopio spaziale James Webb della NASA, mostra l'ammasso di galassie SMACS 0723. Alcune delle galassie appaiono macchiate o allungate a causa di un fenomeno chiamato lente gravitazionale. Questo effetto può aiutare gli scienziati a mappare la presenza di materia oscura nell'universo. Credito:NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI

Uno dei più grandi enigmi dell'astrofisica potrebbe essere risolto rielaborando la teoria della gravità di Albert Einstein? Un nuovo studio co-autore degli scienziati della NASA dice di non ancora.

L'universo si sta espandendo a un ritmo accelerato e gli scienziati non sanno perché. Questo fenomeno sembra contraddire tutto ciò che i ricercatori capiscono sull'effetto della gravità sul cosmo:è come se lanciassi una mela in aria e questa continuasse verso l'alto, sempre più veloce. La causa dell'accelerazione, soprannominata energia oscura, rimane un mistero.

Un nuovo studio dell'International Dark Energy Survey, che utilizza il telescopio da 4 metri Victor M. Blanco in Cile, segna l'ultimo sforzo per determinare se tutto questo sia semplicemente un malinteso:le aspettative su come funziona la gravità alla scala dell'intero universo sono imperfetti o incompleti. Questo potenziale malinteso potrebbe aiutare gli scienziati a spiegare l'energia oscura. Ma lo studio, uno dei test più precisi della teoria della gravità su scala cosmica di Albert Einstein, rileva che l'attuale comprensione sembra essere ancora corretta.

I risultati, scritti da un gruppo di scienziati che include alcuni del Jet Propulsion Laboratory della NASA, sono stati presentati mercoledì 23 agosto alla Conferenza internazionale sulla fisica delle particelle e la cosmologia (COSMO'22) a Rio de Janeiro. Il lavoro aiuta a preparare il terreno per due imminenti telescopi spaziali che sonderanno la nostra comprensione della gravità con una precisione ancora maggiore rispetto al nuovo studio e forse risolveranno finalmente il mistero.

Più di un secolo fa, Albert Einstein sviluppò la sua Teoria della Relatività Generale per descrivere la gravità, e finora ha predetto accuratamente tutto, dall'orbita di Mercurio all'esistenza dei buchi neri. Ma se questa teoria non può spiegare l'energia oscura, hanno sostenuto alcuni scienziati, allora forse hanno bisogno di modificare alcune delle sue equazioni o aggiungere nuovi componenti.

Per scoprire se è così, i membri del Dark Energy Survey hanno cercato prove che la forza della gravità sia variata nel corso della storia dell'universo o su distanze cosmiche. Una scoperta positiva indicherebbe che la teoria di Einstein è incompleta, il che potrebbe aiutare a spiegare l'accelerazione dell'espansione dell'universo. Hanno anche esaminato i dati di altri telescopi oltre a Blanco, incluso il satellite Planck dell'ESA (Agenzia spaziale europea), e sono giunti alla stessa conclusione.

The study finds Einstein's theory still works. So no explanation for dark energy yet. But this research will feed into two upcoming missions:ESA's Euclid mission, slated for launch no earlier than 2023, which has contributions from NASA; and NASA's Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, targeted for launch no later than May 2027. Both telescopes will search for changes in the strength of gravity over time or distance.

Blurred Vision

How do scientists know what happened in the universe's past? By looking at distant objects. A light-year is a measure of the distance light can travel in a year (about 6 trillion miles, or about 9.5 trillion kilometers). That means an object one light-year away appears to us as it was one year ago, when the light first left the object. And galaxies billions of light-years away appear to us as they did billions of years ago. The new study looked at galaxies stretching back about 5 billion years in the past. Euclid will peer 8 billion years into the past, and Roman will look back 11 billion years.

The galaxies themselves don't reveal the strength of gravity, but how they look when viewed from Earth does. Most matter in our universe is dark matter, which does not emit, reflect, or otherwise interact with light. While scientists don't know what it's made of, they know it's there, because its gravity gives it away:Large reservoirs of dark matter in our universe warp space itself. As light travels through space, it encounters these portions of warped space, causing images of distant galaxies to appear curved or smeared. This was on display in one of first images released from NASA's James Webb Space Telescope.

Dark Energy Survey scientists search galaxy images for more subtle distortions due to dark matter bending space, an effect called weak gravitational lensing. The strength of gravity determines the size and distribution of dark matter structures, and the size and distribution in turn determine how warped those galaxies appear to us. That's how images can reveal the strength of gravity at different distances from Earth and distant times throughout the universe's history. The group has now measured the shapes of over 100 million galaxies, and so far, the observations match what's predicted by Einstein's theory.

"There is still room to challenge Einstein's theory of gravity, as measurements gets more and more precise," said study co-author Agnès Ferté, who conducted the research as a postdoctoral researcher at JPL. "But we still have so much to do before we're ready for Euclid and Roman. So it's essential we continue to collaborate with scientists around the world on this problem as we've done with the Dark Energy Survey." + Esplora ulteriormente