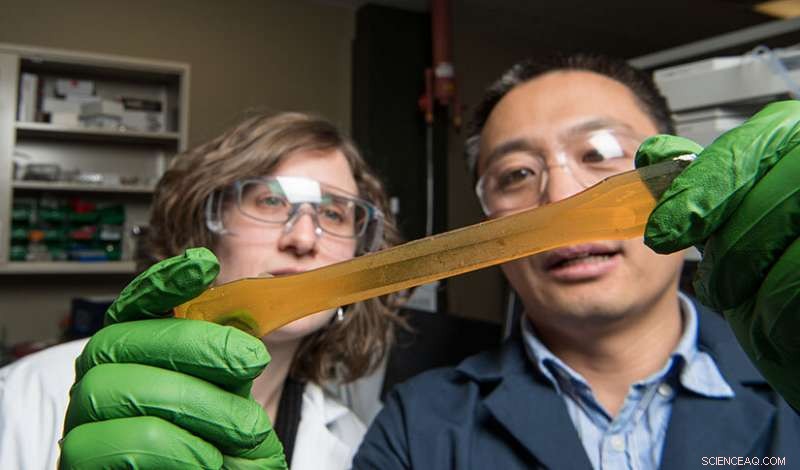

Una formula rinnovabile innovativa:il ricercatore del NREL Tao Dong (a destra) e l'ex stagista Stephanie Federle (a sinistra) esaminano resina poliuretanica atossica, una promettente alternativa al poliuretano convenzionale. Credito:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

Senza esso, il mondo potrebbe essere un po' meno morbido e un po' meno caldo. Il nostro abbigliamento ricreativo potrebbe versare meno acqua. Le solette delle nostre scarpe da ginnastica potrebbero non fornire lo stesso supporto per l'arco terapeutico. La venatura del legno nei mobili finiti potrebbe non "esplodere".

Infatti, il poliuretano, una plastica comune in applicazioni che vanno dalle schiume spruzzabili agli adesivi alle fibre sintetiche per abbigliamento, è diventato un punto fermo del 21° secolo, aggiungendo comodità, comfort, e anche la bellezza a numerosi aspetti della vita quotidiana.

La grande versatilità del materiale, che attualmente è costituito in gran parte da sottoprodotti del petrolio, ha reso il poliuretano la plastica di riferimento per una gamma di prodotti. Oggi, ogni anno nel mondo vengono prodotti più di 16 milioni di tonnellate di poliuretano.

"Pochissimi aspetti della nostra vita non sono toccati dal poliuretano, " rifletté Phil Pienkos, un chimico che si è recentemente ritirato dal National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) dopo quasi 40 anni di ricerca.

Ma Pienkos, che ha costruito una carriera alla ricerca di nuovi modi per produrre combustibili e materiali a base biologica, ha affermato che c'è una spinta crescente a ripensare al modo in cui viene prodotto il poliuretano.

"I metodi attuali si basano in gran parte su sostanze chimiche tossiche e petrolio non rinnovabile, " ha detto. "Volevamo sviluppare una nuova plastica con tutte le proprietà utili dei poli convenzionali, ma senza i costosi effetti collaterali ambientali".

Era possibile? I risultati del laboratorio danno un sonoro sì.

Attraverso una nuova chimica che utilizza risorse non tossiche come l'olio di semi di lino, grasso di scarto, o anche alghe, Pienkos e il suo collega NREL Tao Dong, esperto in ingegneria chimica, hanno sviluppato un metodo innovativo per la produzione di poliuretano rinnovabile senza precursori tossici.

È una svolta con il potenziale per rendere più verde il mercato di prodotti che vanno dalle calzature, alle automobili, ai materassi, e oltre.

Ma per afferrare il puro peso della realizzazione, è utile guardare indietro a come è avvenuto il progresso scientifico, una storia che spazia dai fondamenti chimici del poliuretano convenzionale, nel laboratorio delle alghe dove è emersa per la prima volta l'idea di una nuova chimica, e si snoda verso nuove partnership aziendali che gettano le basi per un promettente futuro di commercializzazione.

Una questione di chimica

Quando il poliuretano divenne disponibile in commercio per la prima volta negli anni '50, è rapidamente cresciuto in popolarità per l'uso in numerosi prodotti e applicazioni. Ciò era dovuto in gran parte alle proprietà dinamiche e sintonizzabili del materiale, così come la disponibilità e l'accessibilità dei componenti a base di petrolio utilizzati per realizzarlo.

Attraverso un processo chimico intelligente che utilizza polioli e isocianati, gli elementi costitutivi di base dei poliuretani convenzionali, i produttori possono personalizzare le loro formulazioni per produrre una straordinaria varietà di materiali poliuretanici, ciascuno con proprietà uniche e utili.

Producendo da un poliolo a catena lunga, Per esempio, potrebbe produrre schiume flessibili per un materasso morbido come un cuscino. Un'altra formulazione potrebbe produrre un liquido ricco che, quando spalmato sui mobili, protegge e rivela la bellezza intrinseca della venatura del legno. Un terzo lotto potrebbe includere anidride carbonica (CO 2 ) per espandere il materiale, producendo una schiuma spruzzabile che si asciuga in un isolamento rigido e poroso, perfetto per trattenere il calore in una casa.

"Questa è la bellezza dell'isocianato, " ha detto Dong riflettendo sul poliuretano convenzionale, "la sua capacità di formare schiume".

Ma Dong ha detto che gli isocianati portano svantaggi significativi, pure. Sebbene queste sostanze chimiche abbiano tassi di reattività rapidi, rendendoli altamente adattabili a molte applicazioni industriali, sono anche altamente tossici, e sono prodotti da una materia prima ancora più tossica, fosgene. Quando inalato, gli isocianati possono portare a una serie di effetti negativi sulla salute, come la pelle, occhio, e irritazione alla gola, asma, e altri gravi problemi polmonari.

"Se vengono bruciati prodotti contenenti poliuretani convenzionali, quegli isocianati vengono volatilizzati e rilasciati nell'atmosfera, " ha aggiunto Pienkos. Anche semplicemente spruzzando poliuretano da usare come isolante, Pienkos ha detto, può aerosolizzare isocianato, richiedendo ai lavoratori di prendere precauzioni attente per proteggere la loro salute.

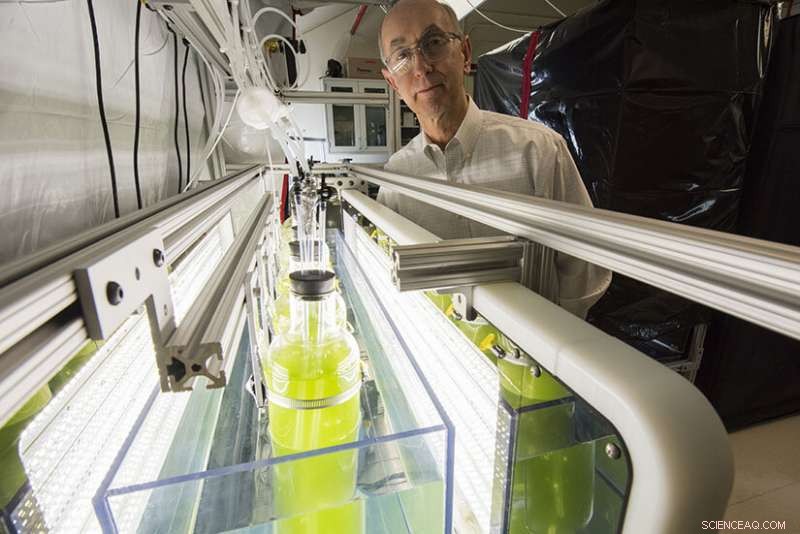

In pensione da poco, Phil Pienkos (nella foto) ha fondato una nuova società, Rinnovabili Polaris, per aiutare ad accelerare la commercializzazione del nuovo poliuretano, un'idea che originariamente è nata dalla sua ricerca sui biocarburanti alghe al NREL. Credito:Dennis Schroeder, NREL

To try and tackle these and other issues—such as reliance on petrochemicals—scientists from labs around the world have begun looking for new ways to synthesize polyurethane using bio-based resources. But these efforts have largely had mixed results. Some lacked the performance needed for industry applications. Others were not completely renewable.

The challenge to improve polyurethane, poi, remained ripe for innovation.

"We can do better than this, " thought Pienkos five years ago when he first encountered the predicament. Energized by the opportunity, he joined with Dong and Lieve Laurens, also of NREL, on a search for a better polyurethane chemistry.

Rethinking the Building Blocks of Polyurethane

The idea grew from a seemingly unrelated laboratory problem:lowering the cost of algae biofuels. As with many conventional petrochemical refining processes, biofuel refiners look for ways to use the coproducts of their processes as a source of revenue.

The question becomes much the same for algae biorefining. Can the waste lipids and amino acids from the process become ingredients for a prized recipe for polyurethane that is both renewable and nontoxic?

For Dong, answering the question at the basic chemical level was the easy part—of course they could. Scientists in the 1950s had shown it was possible to synthesize polyurethane from non-isocyanate pathways.

The real challenge, Dong said, was figuring out how to speed up that reaction to compete with conventional processes. He needed to produce polymers that performed at least as well as conventional materials, a major technical barrier to commercializing bio-based polyurethanes.

"The reactivity of the non-isocyanate, bio-based processes described in the literature is slower, " Dong explained. "So we needed to make sure we had reactivity comparable to conventional chemistry."

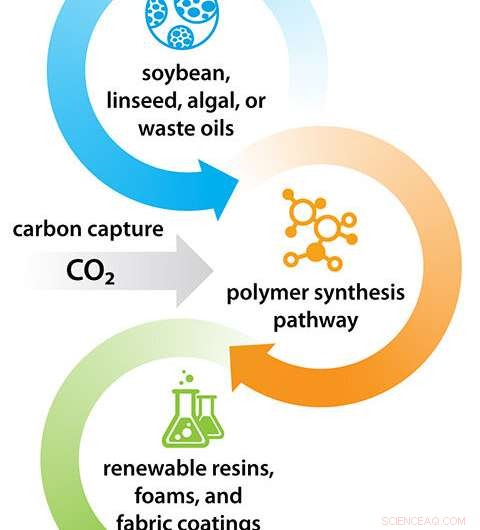

NREL's process overcomes the barrier by developing bio-based formulas through a clever chemical process. It begins with an epoxidation process, which prepares the base oil—anything from canola oil or linseed oil to algae or food waste—for further chemical reactions. By reacting these epoxidized fatty acids with CO 2 from the air or flue gas, carbonated monomers are produced. Infine, Dong combines the carbonated monomers with diamines (derived from amino acids, another bio-based source) in a polymerization process that yields a material that cures into a resin—non-isocyanate polyurethane.

By replacing petroleum-based polyols with select natural oils, and toxic isocyanates with bio-based amino acids, Dong had managed to synthesize polymers with properties comparable to conventional polyurethane. In altre parole, he had developed a viable renewable, nontoxic alternative to conventional polyurethane.

And the chemistry had an added environmental benefit, pure.

"As much of 30% by weight of the final polymer is CO 2 , " Pienkos said, adding that the numbers are even more impressive when considering the CO 2 absorbed by the plants or algae used to create the oils and amino acids in the first place.

CO 2 , a ubiquitous greenhouse gas, is often considered an unfortunate waste product of various industrial processes, prompting many companies to look for ways to absorb it, eliminate it, or even put it to good use as a potential source of profit. By incorporating CO 2 into the very structure of their polyurethane, Pienkos and Dong had provided a pathway for boosting its value.

"That means less raw material per pound of polymer, costo più basso, and a lower overall carbon footprint, " Pienkos continued. "It looks to us that this offers remarkable sustainability opportunities."

A Sought-After Renewable Solution Finds Its Commercial Feet

The next step was to see if the process could be commercialized, scaled up to meet the demands of the market.

The building blocks of poly—NREL's chemistry reacts natural oils with readily available carbon dioxide to produce renewable, nontoxic polyurethanes—a pathway for creating a variety of green materials and products. Credito:National Renewable Energy Laboratory

Dopotutto, renewable or not, polyurethane needs to demonstrate the properties that consumers expect from brand-name products. The process to create it must also match companies' manufacturing processes, allowing them to "drop in" the new material without prohibitively costly upgrades to facilities or equipment.

"That's why we need to work with industry partners, " Dong explained, "to make sure our research aligns with their manufacturing processes."

In the two short years since Pienkos and Dong first demonstrated the viability of producing fully renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, several companies have already contributed resources and research partnerships in the push for its commercialization.

A 2020 U.S. Department of Energy Technology Commercialization Fund award, Per esempio, brought in $730, 000 of federal funding to help develop the technology, as well as matching "in kind" cost share from the outdoor clothing company Patagonia, the mattress company Tempur Sealy, and a start-up biotechnology company called Algix.

And Pienkos says companies from other industries have shown preliminary interest, pure. "These companies believe there is promise in this, " Egli ha detto.

Their interest could partly be due to the tunability of Pienkos and Dong's approach, which lets them, much like conventional methods, create polymers that match industry standards.

"We've demonstrated that the chemistry is tunable, " Dong said. "We can control the final performance through our approach."

By controlling the epoxidation process or amount of carbonization, Per esempio, the process can be suited to meet the performance needs of a product. That may give the outsoles of a pair of running shoes enough flexibility and strength to endure many miles pounding into hot or cold asphalt. Or it may give a mattress a balance of stiffness and support.

"It's got regulation push. It's got market pull. It's got the potential to compete with non-renewables on the basis of cost. It's got a lower carbon footprint. It's got everything, " Pienkos said of the opportunities for commercialization. "This became the most exciting aspect of my career at NREL. Così, when I retired, I decided that I want to make this real. I want to see this technology actually make it into the marketplace."

After retiring last April, Pienkos went on to establish a company, Polaris Renewables, to help accelerate the commercialization of the novel polyurethane. Così, while he continues with his responsibilities as an NREL emeritus researcher, he is also doing outreach to industry to find additional corporate partners, especially in the fashion industry through the international sustainability initiative Fashion for Good.

"In the fashion industry, customers are demanding sustainability, " he explained. "They will pay something of a green premium if you can demonstrate a lower carbon footprint, better end of life disposition."

Infatti, for both Pienkos and Dong, the breakthrough in renewable, nontoxic polyurethane has become more than an exciting scientific venture. It offers the world a pathway for products that leave a lighter mark on the environment.

"I think this is a great opportunity to solve the plastic pollution problem, " Dong said. "We need to save our environment, and part of that begins with making plastic renewable."

Pienkos, pure, thinks that a commercial success in this venture could be a catalyst that spurs further growth and further success in bringing renewable, greener products to the market.

"This could be a success story for NREL, " he said. "A success here means a great deal to the world."

In questo caso, success might be measured in more than the affordability of the production process or the carbon uptake of the polyurethane chemistry. In a world with NREL's renewable, nontoxic polyurethane, success might be something we can truly feel in the durability of our clothing, in the comfort our shoes provide, or in the rejuvenation we feel after sleeping on a memory foam mattress.