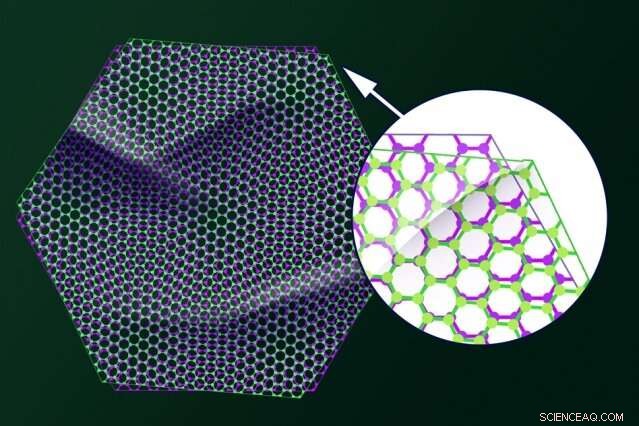

In questa illustrazione, due fogli di grafene sono impilati insieme con un angolo "magico" leggermente sfalsato, che può diventare un isolante o un superconduttore. “Abbiamo messo un foglio di grafene sopra l'altro, simile a mettere un involucro di plastica sopra l'involucro di plastica, ” afferma il professore del MIT Pablo Jarillo-Herrero. “Ti aspetteresti che ci siano rughe, e regioni dove i due fogli sarebbero un po' attorcigliati, alcuni meno contorti, proprio come vediamo nel grafene.” Credito:José-Luis Olivares, MIT

Costituito da un singolo strato di atomi di carbonio collegati in un motivo esagonale a nido d'ape, la struttura del grafene è semplice e apparentemente delicata. Dalla sua scoperta nel 2004, gli scienziati hanno scoperto che il grafene è in effetti eccezionalmente forte. E sebbene il grafene non sia un metallo, conduce elettricità a velocità ultraelevate, meglio della maggior parte dei metalli.

Nel 2018, Gli scienziati del MIT guidati da Pablo Jarillo-Herrero e Yuan Cao hanno scoperto che quando due fogli di grafene vengono impilati insieme con un angolo "magico" leggermente sfalsato, la nuova struttura "twisted" del grafene può diventare sia un isolante, impedendo completamente all'elettricità di fluire attraverso il materiale, o paradossalmente, un superconduttore, in grado di far passare gli elettroni senza resistenza. È stata una scoperta monumentale che ha contribuito a lanciare un nuovo campo noto come "twistronics, " lo studio del comportamento elettronico nel grafene attorcigliato e altri materiali.

Ora il team del MIT riporta i loro ultimi progressi nella twistronica del grafene, in due articoli pubblicati questa settimana sulla rivista Natura .

Nel primo studio, i ricercatori, insieme ai collaboratori del Weizmann Institute of Science, hanno immaginato e mappato per la prima volta un'intera struttura di grafene contorta, con una risoluzione abbastanza fine da poter vedere variazioni molto lievi nell'angolo di torsione locale attraverso l'intera struttura.

I risultati hanno rivelato regioni all'interno della struttura in cui l'angolo tra gli strati di grafene si è leggermente allontanato dall'offset medio di 1,1 gradi.

Il team ha rilevato queste variazioni con una risoluzione angolare ultraelevata di 0,002 gradi. È equivalente a poter vedere l'angolo di una mela contro l'orizzonte da un miglio di distanza.

Hanno scoperto che le strutture con una gamma più ristretta di variazioni angolari avevano proprietà esotiche più pronunciate, come isolamento e superconduttività, rispetto a strutture con una gamma più ampia di angoli di torsione.

"Questa è la prima volta che viene mappato un intero dispositivo per vedere qual è l'angolo di torsione in una determinata regione del dispositivo, " dice Jarillo-Herrero, il Cecil e Ida Green Professore di Fisica al MIT. "E vediamo che puoi avere un po' di variazione e mostrare ancora la superconduttività e altra fisica esotica, ma non può essere troppo. Ora abbiamo caratterizzato quanta variazione di torsione puoi avere, e qual è l'effetto di degradazione di averne troppo."

Nel secondo studio, il rapporto del team ha creato una nuova struttura di grafene contorta con non due, ma quattro strati di grafene. Hanno osservato che la nuova struttura ad angolo magico a quattro strati è più sensibile a determinati campi elettrici e magnetici rispetto al suo predecessore a due strati. Ciò suggerisce che i ricercatori potrebbero essere in grado di studiare in modo più semplice e controllabile le proprietà esotiche del grafene ad angolo magico nei sistemi a quattro strati.

"Questi due studi mirano a comprendere meglio il comportamento fisico sconcertante dei dispositivi twistronici ad angolo magico, "dice Cao, uno studente laureato al MIT. "Una volta capito, i fisici ritengono che questi dispositivi potrebbero aiutare a progettare e progettare una nuova generazione di superconduttori ad alta temperatura, dispositivi topologici per l'elaborazione dell'informazione quantistica, e tecnologie a basso consumo energetico".

Come le rughe nell'involucro di plastica

Da quando Jarillo-Herrero e il suo gruppo hanno scoperto per la prima volta il grafene ad angolo magico, altri hanno colto al volo l'occasione di osservarne e misurarne le proprietà. Diversi gruppi hanno immaginato strutture ad angoli magici, utilizzando la microscopia a effetto tunnel, o STM, una tecnica che scansiona una superficie a livello atomico. Però, i ricercatori sono stati in grado di scansionare solo piccole chiazze di grafene ad angolo magico, che si estende al massimo qualche centinaio di nanometri quadrati, utilizzando questo approccio.

"Esaminare un'intera struttura su scala micron per esaminare milioni di atomi è qualcosa per cui STM non è più adatto, " dice Jarillo-Herrero. "In linea di principio si potrebbe fare, ma ci vorrebbe un'enorme quantità di tempo."

Quindi il gruppo si è consultato con i ricercatori del Weizmann Institute for Science, che avevano sviluppato una tecnica di scansione che chiamano "scanning nano-SQUID, " dove SQUID sta per Superconducting Quantum Interference Device. Gli SQUID convenzionali assomigliano a un piccolo anello diviso in due, le cui due metà sono realizzate in materiale superconduttore e unite tra loro da due giunzioni. Fit around the tip of a device similar to an STM, a SQUID can measure a sample's magnetic field flowing through the ring at a microscopic scale. The Weizmann Institute researchers scaled down the SQUID design to sense magnetic fields at the nanoscale.

When magic-angle graphene is placed in a small magnetic field, it generates persistent currents across the structure, due to the formation of what are known as "Landau levels." These Landau levels, and hence the persistent currents, are very sensitive to the local twist angle, ad esempio, resulting in a magnetic field with a different magnitude, depending on the precise value of the local twist angle. In questo modo, the nano-SQUID technique can detect regions with tiny offsets from 1.1 degrees.

"It turned out to be an amazing technique that can pick up miniscule angle variations of 0.002 degrees away from 1.1 degrees, " Jarillo-Herrero says. "This was very good for mapping magic-angle graphene."

The group used the technique to map two magic-angle structures:one with a narrow range of twist variations, and another with a broader range.

"We placed one sheet of graphene on top of another, similar to placing plastic wrap on top of plastic wrap, " Jarillo-Herrero says. "You would expect there would be wrinkles, and regions where the two sheets would be a bit twisted, some less twisted, just as we see in graphene."

They found that the structure with a narrower range of twist variations had more pronounced properties of exotic physics, such as superconductivity, compared with the structure with more twist variations.

"Now that we can directly see these local twist variations, it might be interesting to study how to engineer variations in twist angles to achieve different quantum phases in a device, " dice Cao.

Tunable physics

Over the past two years, researchers have experimented with different configurations of graphene and other materials to see whether twisting them at certain angles would bring out exotic physical behavior. Jarillo-Herrero's group wondered whether the fascinating physics of magic-angle graphene would hold up if they expanded the structure, to offset not two, but four graphene layers.

Since graphene's discovery nearly 15 years ago, a huge amount of information has been revealed about its properties, not just as a single sheet, but also stacked and aligned in multiple layers—a configuration that is similar to what you find in graphite, or pencil lead.

"Bilayer graphene—two layers at a 0-degree angle from each-other—is a system whose properties we understand well, " Jarillo-Herrero says. "Theoretical calculations have shown that in a bilayer-on-top-of-bilayer structure, the range of angles over which interesting physics would happen is larger. So this type of structure might be more forgiving in terms of making devices."

Partly inspired by this theoretical possibility, the researchers fabricated a new magic-angle structure, offsetting one graphene bilayer with another bilayer by 1.1 degrees. They then connected the new "double-layer" twisted structure to a battery, applied a voltage, and measured the current that flowed through the device as they placed the structure under various conditions, such as a magnetic field, and a perpendicular electric field.

Just like magic-angle structures made from two layers of graphene, the new four-layered structure showed an exotic insulating behavior. But uniquely, the researchers were able to tune this insulating property up and down with an electric field—something that's not possible with two-layered magic-angle graphene.

"This system is highly tunable, meaning we have a lot of control, which will allow us to study things we cannot understand with monolayer magic-angle graphene, " dice Cao.

"It's still very early in the field, " Jarillo-Herrero says. "For the moment, the physics community is still fascinated just by the phenomena of it. People fantasize about what type of devices we could make but realize it's still too early and we have so much yet to learn about these systems."

This story is republished courtesy of MIT News (web.mit.edu/newsoffice/), a popular site that covers news about MIT research, innovation and teaching.