Un peschereccio Brixham del XIX secolo di William Adolphus Knell. Credito:Museo Marittimo Nazionale/Wikipedia

Le barche britanniche erano in inferiorità numerica di circa otto a uno rispetto ai francesi. In poco tempo ci furono collisioni e furono lanciati proiettili. Gli inglesi furono costretti a ritirarsi, rientrando in porto con i finestrini rotti ma fortunatamente nessun ferito.

Il conflitto alla base di questa scaramuccia tra pescatori britannici e francesi nella baia di Senna alla fine di agosto 2018 è stato rapidamente soprannominato dalla stampa la "guerra delle capesante". I francesi avevano cercato di impedire alle draghe britanniche di pescare legalmente i letti nelle acque nazionali francesi. Ma l'incidente ha messo in luce tensioni che ribollivano da molti anni.

Nell'ambito della politica comune della pesca (PCP) dell'Unione europea, i pescatori britannici avevano il diritto legale di pescare in queste acque, così come tutte le barche di uno stato membro dell'UE. La complicazione derivava da un regolamento francese che impediva alle imbarcazioni locali di pescare in queste acque tra il 16 maggio e il 30 settembre di ogni anno, al fine di consentire agli stock di riprendersi dal raccolto annuale. Ma sotto la PCP, un paese dell'UE non ha l'autorità per impedire alla flotta di un altro Stato membro di pescare nelle sue acque.

Questa stranezza della PCP ha impedito ai pescatori francesi di dragare le capesante fino al 1 ottobre, e costretti a stare a guardare mentre le flotte di altri paesi raccoglievano quella che consideravano una risorsa francese dalle acque francesi. Quando arrivarono le barche britanniche, i pescatori francesi hanno assunto il ruolo di custodi della loro risorsa, azioni che ritenevano giustificate ma considerate illegali dall'industria della pesca britannica.

Questo incidente in un piccolo angolo di un mare comune dell'UE è stato risolto in poche settimane grazie a un nuovo accordo su come i due paesi avrebbero condiviso il raccolto di capesante. Ma le tensioni di fondo che la PCP ha creato sulla condivisione delle risorse nazionali sono molto più profonde, con la sensazione che le regole non consentano un uso equo dei mari.

Questo senso di ingiustizia è stato ovviamente espresso nel ruolo svolto dalla pesca nella decisione della Gran Bretagna di lasciare l'UE. Gli attivisti hanno promesso che "riprendere il controllo" delle acque britanniche avrebbe consentito al paese di rilanciare la sua industria della pesca in declino da tempo e le comunità che fanno affidamento su di essa.

Tuttavia, indipendentemente dall'impatto che la PCP ha avuto sui pescatori britannici, il loro futuro dopo la Brexit dipende molto da qualsiasi futuro accordo commerciale che il governo negozierà con l'UE. E la storia di come la Gran Bretagna ha risposto ai conflitti sui diritti di pesca molto più grandi della guerra delle capesante non è di buon auspicio per l'industria.

L'inizio del declino

La ricerca sull'attività di pesca mostra che il declino dell'industria della pesca britannica è iniziato molto prima della creazione di qualsiasi politica europea della pesca. Infatti, le sue ultime origini possono essere ricondotte a una fonte sorprendente:l'espansione delle ferrovie alla fine dell'Ottocento.

pesca a strascico, sotto il potere della vela, esisteva da più di 500 anni. Ma senza refrigerazione, il pesce poteva essere consegnato per la vendita solo in aree vicine ai porti. L'avvento della rete ferroviaria ha significato che il pesce poteva essere trasportato nell'entroterra verso le grandi città.

Per soddisfare ulteriormente questa crescente domanda, i pescherecci a vapore iniziarono a sostituire i pescherecci a vela dal 1880 in poi. La potenza di queste navi a vapore aumentava notevolmente la portata della pesca a strascico e permetteva loro di trainare più a lungo e più lontano dal porto mentre trainavano reti più grandi. I pescherecci a vapore britannici si avventurarono più lontano dalla Gran Bretagna in cerca di pesce, con l'espansione delle zone di pesca fino alla Groenlandia, la Norvegia settentrionale e il Mare di Barent, Islanda e Isole Faroe.

Ma già nel 1885, sono state espresse preoccupazioni sul fatto che questo progresso tecnologico stesse avendo un impatto negativo sia sugli stock ittici che sul loro habitat. L'evidenza dei registri dell'attività di pesca mostra che questo miglioramento della tecnologia e l'aumento delle dimensioni della flotta peschereccia sono stati esattamente dietro l'aumento degli sbarchi.

Il boom della pesca che le ferrovie avevano scatenato si rivelò insostenibile, e la pesca eccessiva risultante alla fine manderebbe il settore in una recessione a lungo termine. Dopo decenni di sempre più pesca, gli sbarchi alla fine iniziarono a diminuire dopo la seconda guerra mondiale, una tendenza che è proseguita nella seconda metà del XX secolo e nel nuovo millennio.

Compensare, le dimensioni e la potenza della flotta continuarono ad aumentare poiché era necessario uno sforzo maggiore per catturare pesci sempre più scarsi. Dalla fine degli anni Cinquanta, la quantità di pesce sbarcato per unità di potenza è diminuita a un ritmo più rapido rispetto agli sbarchi di pesce, poiché la flotta ha continuato a impegnarsi sempre di più per mantenere le dimensioni delle catture. Però, questo sforzo è stato del tutto vano e nel 1980 le catture erano scese al punto più basso in un secolo.

L'Odino islandese e la HMS Scilla si scontrano nel Nord Atlantico durante la "terza guerra del merluzzo" negli anni '70. Credito:Isaac Newton/www.hmsbacchante.co.uk

Guerre di merluzzo

La pesca eccessiva non è stata l'unica ragione per il declino, però. La caduta degli stock ittici combinata con i miglioramenti nella portata e nella potenza della flotta negli anni del dopoguerra ha portato i pescatori britannici a cercare nuove acque, con più barche che si allontanano dal Regno Unito per catturare abbastanza pesce per soddisfare la domanda interna. E questa pesca a strascico a lungo raggio ha portato la flotta britannica in conflitto con l'Islanda.

I pescatori britannici avevano pescato in queste acque dal XV secolo. Però, L'industria della pesca islandese iniziò a risentirsi di questo quando i pescherecci a vapore iniziarono a pescare al largo dell'Islanda alla fine del XIX secolo. Ha portato ad accuse che i pescherecci da traino britannici stavano danneggiando le zone di pesca e stavano esaurendo gli stock. Nel 1952, L'Islanda ha dichiarato una zona di quattro miglia intorno al proprio paese per fermare l'eccessiva pesca straniera, anche se i pesci non si attengono ai confini creati dall'uomo e gli stock potrebbero ancora essere esauriti al di fuori di questa zona. La decisione dell'Islanda ha ottenuto una risposta dal Regno Unito, che vietava l'importazione di pesce islandese. Essendo uno dei principali mercati di esportazione per l'industria più importante dell'Islanda, speravano che questo li avrebbe portati al tavolo dei negoziati.

Nel 1958, in un contesto di diplomazia fallita, L'Islanda ha esteso questa zona a 12 miglia e ha vietato alle flotte straniere di pescare in queste acque, a dispetto del diritto internazionale. Ha portato alla prima di quelle che divennero note come le Guerre del Merluzzo, un atto in tre fasi che durò quasi 20 anni.

Durante la prima guerra del merluzzo, Le fregate della Royal Navy hanno accompagnato la flotta del Regno Unito nella zona di esclusione dell'Islanda per continuare la loro pesca. Ne seguì una partita al gatto col topo tra le navi della guardia costiera islandese e i pescherecci britannici. In risposta ai tentativi di catturarli, i pescherecci hanno speronato le navi della guardia costiera e la guardia costiera ha minacciato di aprire il fuoco, anche se incidenti importanti sono stati evitati.

Nel 1961, i due paesi alla fine hanno raggiunto un accordo che ha permesso all'Islanda di mantenere la sua zona di 12 miglia. In cambio, al Regno Unito è stato concesso l'accesso condizionato a queste acque.

Nel 1972, però, la pesca eccessiva al di fuori di questo limite era peggiorata e l'Islanda ha esteso la sua zona esclusiva a 50 miglia e poi tre anni dopo, a 200 miglia. Entrambe queste mosse hanno portato a ulteriori scontri tra i pescherecci da traino islandesi e le navi di scorta della Royal Navy, rispettivamente soprannominata la seconda e la terza guerra del merluzzo.

Icelandic Coastguard vessels towed devices designed to cut the steel trawl wires (hawsers) of the British trawlers – and vessels from all sides were involved in deliberate collisions. Although these clashes were mainly bloodless, a British fisher was seriously injured when he was hit by a severed hawser and an Icelandic engineer died while repairing damage to a trawler that had clashed with a Royal Navy frigate.

In January 1976, British naval frigate HMS Andromeda collided with Thor, an Icelandic gunboat, which also sustained a hole in its hull. While British officials called the collision a "deliberate attack", the Icelandic Coastguard accused the Andomeda of ramming Thor by overtaking and then changing course. Eventually NATO intervened and another agreement was reached in May 1976 over UK access and catch limits. This agreement gave 30 vessels access to Iceland's waters for six months.

NATO's involvement in the dispute had little to do with fisheries and a large amount to do with the Cold War. Iceland was a member of NATO, and therefore aligned to the US, with a substantial US military presence in Iceland at the time. Iceland believed that NATO should intervene in the dispute but it had up until that point resisted. Popular feeling against NATO grew in Iceland and the US became concerned that this strategically important island nation – which allowed control of the Greenland Iceland UK (GIUK) gap, an anti-submarine choke point – could leave NATO and worse, align itself with the Soviets.

Amid protests at the US military base in Iceland demanding the expulsion of the Americans, and growing calls from Icelandic politicians that they should leave NATO, the US put pressure on the British to concede in order to protect the NATO alliance. The agreement brought to an end more than 500 years of unrestricted British fishing in these waters.

The loss of these Atlantic fishing grounds cost 1, 500 jobs in the home ports of the UK's distant water fleet, concentrated around Scotland and the north-east of England, with many more jobs lost in shore-based support industries. This had a significant negative impact on the fishing communities in these areas.

The UK also established its own 200-mile limit in response to Iceland's exclusion zone. These limits were eventually incorporated in the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, giving similar rights to every sovereign nation. The creation of these "exclusive economic zones" (EEZ) was the first time that the international community had recognised that nations could own all of the resources that existed within the seas that surrounded them and exclude other nations from exploiting these resources.

The UK now owned the rights to the 200-mile zone around its islands, which contained some of the richest fishing grounds in Europe but up until this point the principle of "open seas" had existed, with Britain its most vocal champion. Fishing nations, had fished the high seas within 200 miles of their own and others coasts for centuries and now were restricted to their own.

British trawler Coventry City passes Icelandic Coastguard patrol vessel Albert off the Westfjords in 1958 during the first Cod War. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia

Economic trade offs

Britain's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), però, wasn't that exclusive.

On joining the European Economic Community (the forerunner to the EU) in 1972, the UK had agreed to a policy of sharing access to its waters with all member states, and gaining access to the waters of other countries in return. The UN convention effectively gave the EEC one giant EEZ.

The UK government was willing to enter into the agreement as fisheries were one part of overall negotiations that would allow the UK to export goods and services to the European continent with significantly reduced trade barriers.

Although the fishing industry is of high local importance to fishing communities, it is relatively unimportant to the UK economy as a whole. Nel 2016, the UK fishing industry (which includes the catching sector and all associated industries) was valued at £1.6 billion, against £1.76 trillion for the UK economy as a whole – or just under 1%. The UK's trade with the EU, both import and export, stands at £615 billion a year in comparison.

Enter the Common Fisheries Policy

In 1983, the Common Fisheries Policy was adopted, introducing management of European waters by giving each state a quota for what it could catch, based on a pre-determined percentage of total fishing opportunities. This was known as "relative stability" and was based on each country's historic fishing activity before 1983, which still determines how quotas are allocated today.

The formula that the EEC adopted, based on historic catches, is one of most contentious parts of the CFP for the UK. Many fishers have stories of the years running up to 1983, where foreign vessels increased their fishing activity in UK waters in order to secure a larger share of these fish in perpetuity. Although there is little evidence to support these views, it demonstrates the level of distrust in both the system, and foreign fishers, from the outset.

Di conseguenza, only 32% of fish caught in the UK EEZ today is caught by UK boats, with most of the remainder taken by vessels from other EU states, Norway and the Faroe Islands (who have also joined the CFP). Perciò, non-UK vessels catch the remaining 68%, about 700, 000 tonnes, of fish a year in the UK EEZ.In return, the UK fleet lands about 92, 000 tonnes a year from other EU countries' waters.

Joining the CFP did not cause a decline in UK fish landings. Però, in its early days, it did nothing to stop it. Fish landings continued to decline – and along with this, the industry itself contracted, using improved technology to offset the decline in stocks. Through the 1980s and into the early part of this century the imbalance – enshrined in the relative stability measure of the CFP – has led to the view that the CFP doesn't work in the UK's interests. Rather it allows the rest of the EU to take advantage of the country's fish stocks.

The CFP's quota system, while credited for helping the industry survive (and even reverse the collapse in fish stocks), is now seen as burdensome and preventing further growth.

A recent academic analysis of the current performance of the CFP showed it was not improving the management of the fish stock resources in any of its 17 criteria and was actually making things worse in seven areas.

Per esempio, a 2013 reform of the CFP introduced the landing obligation, the so-called "discard ban", that was designed to stop vessels discarding fish (bycatch) caught alongside the species they were targeting. Environmentalists, and campaigns backed by celebrities such as Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, have long voiced concerns over incidents of bycatch being dumped by fishers operating under the quota system.

This policy is now seen as potentially disastrous by some representatives of Britain's North Sea fishing fleet, as so many different types of fish live in the waters and bycatch is common and often unavoidable. They are concerned that boats would be forced to fill their holds with commercially worthless fish and return to port early. Or by exhausting their quota for some species early in the season, they would be forced to stay in port for the rest of the year, despite having quotas available for other species. Evidence given to the House of Lords suggests that this situation has not arisen as non-compliance and a lack of enforcement has undermined the discard ban.

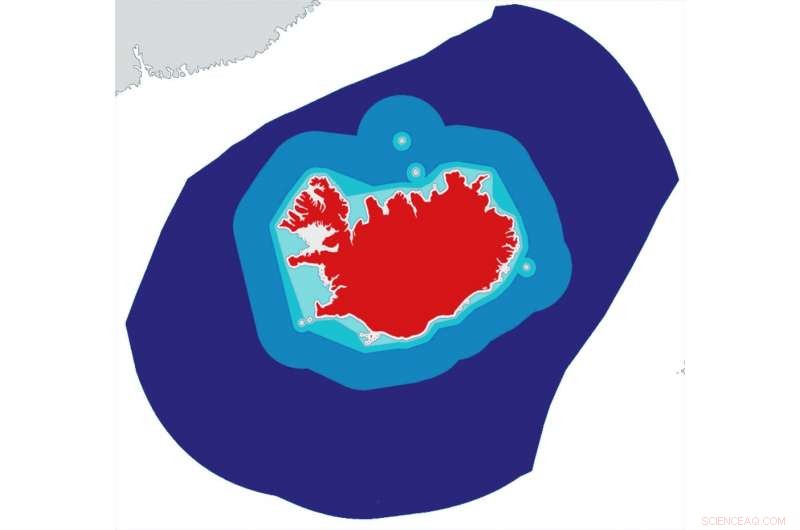

Map of the Icelandic EEZ, and its expansion. Red =Iceland. White =internal waters. Light turquoise =four-mile expansion, 1952. Dark turquoise =12-mile expansion (current extent of territorial waters), 1958. Blue =50-mile expansion, 1972. Dark blue =200-mile expansion (current extent of EEZ), 1975. Credit:Kjallakr/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

When we interviewed fishers in north-east Scotland in 2018, we found many feared such blanket management across the entire EU would continue to damage their industry because it simply does not take into account the local environment that they work in.

Brexit

The depth of feeling among the UK fishing community was illustrated by the voting figures for the EU referendum in June 2016.

In Banff and Buchan, the constituency in Scotland containing Peterhead and Fraserburgh – the largest and third largest fishing ports in the UK respectively – 54% of people voted to leave the EU, with the size of the fishing industry given as the reason for this result. The result compared to 52% for the whole of the UK and just 38% for Scotland. A survey of members of the UK fishing industry before the vote indicated that 92.8% of correspondents believed that doing so would improve the UK fishing industry by some measure.

But will Brexit really bring the fishing revival so many have promised and hoped for? British politicians have promised a renaissance in UK fishing after leaving the EU. A Fisheries Bill was launched by the environment secretary, Michael Gove, with an aim to "take back control of UK waters". Però, no definitive plan to remove the UK from the CFP in a transition deal has been made, nor has the industry been given any answers on future access for EU vessels, the apportionment of any new quota – if indeed the quota system remains as it is – the rules that they will be operating under, or even a date on which this will come into effect.

The UK government is seen by many in the fishing industry to be acting against their interests in pursuit of wider goals, for example by using the industry as a bargaining chip in wider UK trade negotiations with the EU.

The fishing industry's distrust of the government has a long tail:many believe they were sacrificed in 1973 by the then prime minister, Edward Heath, in order to secure access to the single market.

A soured relationship

Ironia della sorte, despite the fishing industry's support for Brexit and the popular campaign promises, our research suggests fishers don't simply want to close British waters to European fleets. We interviewed people who were sympathetic to their fellow fishers from abroad and did not wish to see businesses and livelihoods lost. They favour a re-balancing of quotas over time to allow EU vessels to adapt to the change, with all vessels having to adhere to UK rules. This would avoid any situations similar to the Scallop War by ensuring that all vessels with a quota have to abide by local restrictions.

The EU is the main export market for UK fish and fisheries products accounting for 70% of UK fisheries exports by value. Valued at £1.3 billion, this trade far exceeds the £980m value of fish landed in the UK, due to the added value from the processing sector. Some of the remaining 30% of exports that go to countries outside of the EU are governed by trade agreements negotiated by the EU that reduce trade barriers. So the single market, and additional trade agreements, are crucial to the success of the UK fishing industry.

This reliance on trade into the EU puts the industry in a position where unilaterally preventing access to UK waters would likely be met by reciprocal trade barriers and tariffs. This would increase the cost of their product, while reducing access to their biggest market. The question for the government, poi, is how to balance a political issue against an economic one?

The issue centres on the word "control". If the UK has control of its waters that would simply mean that its government has the power to decide on anything from keeping fishing within UK waters purely for UK vessels, to remaining in or re-entering the CFP, or all points in between. Until the deals are negotiated and signed, the industry will remain in a limbo that has reopened old wounds and reignited distrust in the UK government.

Questo articolo è stato ripubblicato da The Conversation con una licenza Creative Commons. Leggi l'articolo originale.