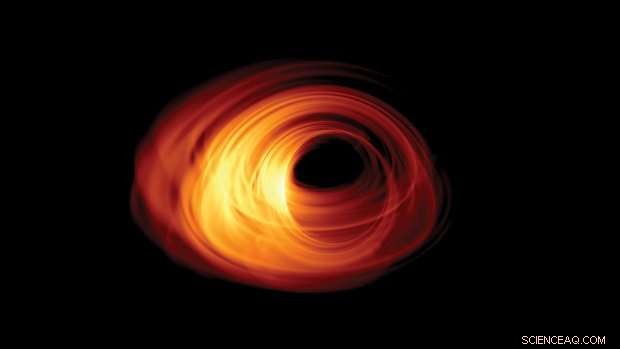

L'ombra di un buco nero circondato da un anello di fuoco in una simulazione generica. Credito:T. Bronzwaer, M. Moscibrodzka, Università H. Falcke Radboud

Nelle regioni oscure dei buchi neri si scontrano due teorie fondamentali che descrivono il nostro mondo. Questi problemi possono essere risolti e i buchi neri esistono davvero? Primo, potremmo doverne vedere uno e gli scienziati stanno cercando di fare proprio questo.

Di tutte le forze in fisica ce n'è una che ancora non capiamo affatto:la gravità.

La gravità è dove la fisica fondamentale e l'astronomia si incontrano, e dove le due teorie più fondamentali che descrivono il nostro mondo - la teoria dei quanti e la teoria dello spaziotempo e della gravità di Einstein (nota anche come teoria della relatività generale) - si scontrano frontalmente.

Le due teorie sono apparentemente incompatibili. E per la maggior parte questo non è un problema. Entrambi vivono in mondi distinti, dove la fisica quantistica descrive il molto piccolo, e la relatività generale descrive le scale più grandi.

Solo quando si arriva a scale molto piccole e gravità estrema, le due teorie si scontrano, e in qualche modo, uno di loro si sbaglia. Almeno in teoria.

Ma c'è un posto nell'universo in cui potremmo effettivamente assistere a questo problema che si verifica nella vita reale e forse persino risolverlo:il bordo di un buco nero. Qui, troviamo la gravità più estrema. C'è solo un problema:nessuno ha mai "visto" un buco nero.

Così, cos'è un buco nero?

Immagina che l'intero dramma del mondo fisico si svolga nel teatro dello spaziotempo, ma la gravità è l'unica "forza" che effettivamente modifica il teatro in cui recita.

La forza di gravità governa l'universo, ma potrebbe anche non essere una forza nel senso tradizionale. Einstein lo descrisse come una conseguenza della deformazione dello spaziotempo. E forse semplicemente non si adatta al modello standard della fisica delle particelle.

Quando una stella molto grande esplode alla fine della sua vita, la sua parte più interna crollerà sotto la sua stessa gravità, poiché non c'è più abbastanza carburante per sostenere la pressione lavorando contro la forza di gravità (sì, la gravità sembra una forza dopotutto, non è vero!).

La materia crolla e nessuna forza in natura è nota per essere in grado di fermare quel crollo, mai.

In un tempo infinito, la stella sarà collassata in un punto infinitamente piccolo:una singolarità – o per darle un altro nome, un buco nero.

Certo, in un tempo finito il nucleo stellare sarà collassato in qualcosa di dimensioni finite e questa sarebbe ancora un'enorme quantità di massa in una regione follemente piccola ed è ancora chiamata buco nero!

I buchi neri non risucchiano tutto ciò che li circonda

interessante, non è vero che un buco nero attirerà inevitabilmente tutto.

Infatti, se stai orbitando attorno a una stella o a un buco nero formato da una stella, non fa differenza, purché la massa sia la stessa. La buona vecchia forza centrifuga e il tuo momento angolare ti terranno al sicuro e ti impediranno di cadere.

Solo quando accendi i tuoi propulsori a razzo giganti per frenare la rotazione, inizierai a cadere verso l'interno.

Però, una volta che cadi verso un buco nero sarai accelerato a velocità sempre più alte, fino a quando non raggiungi la velocità della luce.

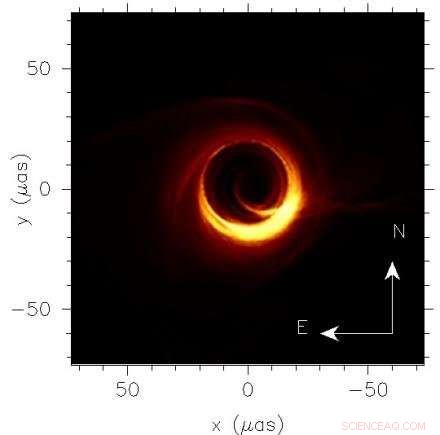

Immagine simulata come previsto per il nero supermassiccio nella galassia M87 alle frequenze osservate con l'Event Horizon Telescope (230 GHz). Attestazione:Moscibrodzka, Falcke, Shiokawa, Astronomia e astrofisica, V. 586, P. 15, 2016, riprodotto con il permesso © ESO

Perché la teoria quantistica e la relatività generale sono incompatibili?

A questo punto tutto va storto come, secondo la relatività generale, niente dovrebbe muoversi più velocemente della velocità della luce.

La luce è il substrato utilizzato nel mondo quantistico per scambiare forze e per trasportare informazioni nel mondo macro. La luce determina la velocità con cui puoi collegare causa e conseguenze.

Se vai più veloce della luce, potevi vedere gli eventi e cambiare le cose prima che accadano. Questo ha due conseguenze:

Se ciò sia vero e se e come la teoria della gravità (o della fisica quantistica) debba essere modificata è una questione di intenso dibattito tra i fisici, e nessuno di noi può dire in che direzione porterà l'argomento alla fine.

Esistono anche i buchi neri?

Certo, tutta questa eccitazione sarebbe solo giustificata, se i buchi neri esistessero davvero in questo universo. Così, fanno?

Nell'ultimo secolo sono emerse prove evidenti che alcune stelle binarie con intense emissioni di raggi X sono in realtà stelle collassate in buchi neri.

Inoltre, nei centri delle galassie troviamo spesso prove di enormi, concentrazioni oscure di massa. Queste potrebbero essere versioni supermassicce di buchi neri, forse formato dalla fusione di molte stelle e nubi di gas che sono sprofondate nel centro di una galassia.

Le prove sono convincenti, ma circostanziale. Almeno le onde gravitazionali ci hanno fatto 'sentire' la fusione dei buchi neri, ma la firma dell'orizzonte degli eventi è ancora sfuggente e finora, in realtà non abbiamo mai "visto" un buco nero:tendono semplicemente ad essere troppo piccoli e troppo lontani e, nella maggior parte dei casi, sì, Nero...

Così, come sarebbe effettivamente un buco nero?

Se potessi guardare dritto in un buco nero vedresti il buio più oscuro, Puoi immaginare.

Ma, le immediate vicinanze di un buco nero potrebbero essere luminose mentre i gas si muovono a spirale verso l'interno, rallentati dalla resistenza dei campi magnetici che trasportano.

A causa dell'attrito magnetico, il gas si riscalderà fino a temperature enormi fino a diverse decine di miliardi di gradi e inizierà a irradiare luce UV e raggi X.

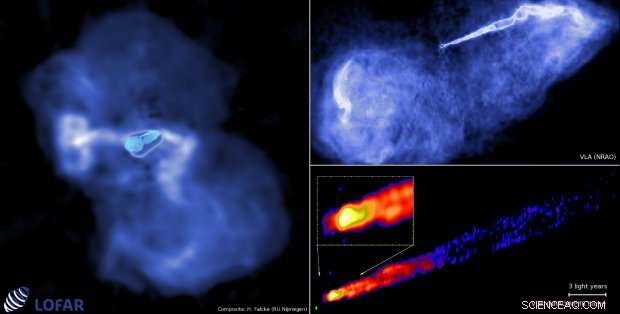

Gli elettroni ultra-caldi che interagiscono con il campo magnetico nel gas inizieranno a produrre un'intensa emissione radio. Così, i buchi neri possono brillare e potrebbero essere circondati da un anello di fuoco che si irradia a molte lunghezze d'onda diverse.

Un anello di fuoco con un buio, centro oscuro

Nel loro stesso centro, però, l'orizzonte degli eventi è ancora in agguato e come un rapace cattura ogni fotone che si avvicina troppo.

Radio images of the jet in the radio galaxy M87 – observed at lower resolution. The left frame is roughly 250, 000 light years across. Magnetic fields threading the supermassive black holes lead to the formation of a highly collimated jet that spits out hot plasma with speeds close to the speed of light . Credit:H. Falcke, Radboud university, with images from LOFAR/NRAO/MPIfR Bonn

Since space is bent by the enormous mass of a black hole, light paths will also be bent and even form into almost concentric circles around the black hole, like serpentines around a deep valley. This effect of circling light was calculated already in 1916 by the famous Mathematician David Hilbert only a few months after Albert Einstein finalised his theory of general relativity.

After orbiting the black hole multiple times, some of the light rays might escape while others will end up in the event horizon. Along this complicated light path, you can literally look into the black hole. The nothingness you see is the event horizon.

If you were to take a photo of a black hole, what you would see would be akin to a dark shadow in the middle of a glowing fog of light. Quindi, we called this feature the shadow of a black hole .

interessante, the shadow appears larger than you might expect by simply taking the diameter of the event horizon. The reason is simply, that the black hole acts as a giant lens, amplifying itself.

Surrounding the shadow will be a thin 'photon ring' due to light circling the black hole almost forever. Further out, you would see more rings of light that arise from near the event horizon, but tend to be concentrated around the black hole shadow due to the lensing effect.

Fantasy or reality?

Is this pure fantasy that can only be simulated in a computer? Or can it actually be seen in practice? The answer is that it probably can.

There are two relatively nearby supermassive black holes in the universe which are so large and close, that their shadows could be resolved with modern technology.

These are the black holes in the center of our own Milky Way at a distance of 26, 000 lightyears with a mass of 4 million times the mass of the sun, and the black hole in the giant elliptical galaxy M87 (Messier 87) with a mass of 3 to 6 billion solar masses.

M87 is a thousand times further away, but also a thousand times more massive and a thousand times larger, so that both objects are expected to have roughly the same shadow diameter projected onto the sky.

Like seeing a grain of mustard in New York from Europe

Coincidentally, simple theories of radiation also predict that for both objects the emission generated near the event horizon would be emitted at the same radio frequencies of 230 GHz and above.

Most of us come across these frequencies only when we have to pass through a modern airport scanner but some black holes are continuously bathed in them.

The radiation has a very short wavelength of about one millimetre and is easily absorbed by water. For a telescope to observe cosmic millimetre waves it will therefore have to be placed high up, on a dry mountain, to avoid absorption of the radiation in the Earth's troposphere.

Effectively, you need a millimetre-wave telescope that can see an object the size of a mustard seed in New York from as far away as Nijmegen in the Netherlands. That is a telescope a thousand times sharper than the Hubble Space Telescope and for millimetre-waves this requires a telescope the size of the Atlantic Ocean or larger.

A virtual Earth-sized telescope

Fortunatamente, we do not need to cover the Earth with a single radio dish, but we can build a virtual telescope with the same resolution by combining data from telescopes on different mountains across the Earth.

The technique is called Earth rotation synthesis and very long baseline interferometry (VLBI). The idea is old and has been tested for decades already, but it is only now possible at high radio frequencies.

Layout of the Event Horizon Telescope connecting radio telescopes around the world (JCMT &SMA in Hawaii, AMTO in Arizona, LMT in Mexico, ALMA &APEX in Chile, SPT on the South Pole, IRAM 30m in Spain). The red lines are to a proposed telescope on the Gamsberg in Namibia that is still being planned. Credit:ScienceNordic / Forskerzonen. Compiled from images provided by the author

The first successful experiments have already shown that event horizon structures can be probed at these frequencies. Now high-bandwidth digital equipment and large telescopes are available to do this experiment on a large scale.

Work is already underway

I am one of the three Principal Investigators of the BlackHoleCam project. BlackHoleCam is an EU-funded project to finally image, measure and understand astrophysical black holes. Our European project is part of a global collaboration known as the Event Horizon Telescope consortium – a collaboration of over 200 scientists from Europe, the Americas, Asia, e dell'Africa. Together we want to take the first picture of a black hole.

In April 2017 we observed the Galactic Center and M87 with eight telescopes on six different mountains in Spain, Arizona, Hawaii, Messico, Chile, and the South Pole.

All telescopes were equipped with precise atomic clocks to accurately synchronise their data. We recorded multiple petabytes of raw data, thanks to surprisingly good weather conditions around the globe at the time.

We are all excited about working with this data. Certo, even in the best of all cases, the images will never look as pretty as the computer simulations. Ma, at least they will be real and whatever we see will be interesting in its own right.

To get even better images telescopes in Greenland and France are being added. Inoltre, we have started raising funds for additional telescopes in Africa and perhaps elsewhere and we are even thinking about telescopes in space.

A 'photo' of a black hole

If we actually succeed in seeing an event horizon, we will know that the problems we have in rhyming quantum theory and general relativity are not abstract problems, but are very real. And we can point to them in the very real shadowy regions of black holes in a clearly marked region of our universe.

This is perhaps also the place where these problems will eventually be solved.

We could do this by obtaining sharper images of the shadow, or maybe by tracing stars and pulsars as they orbit around black holes, through measuring spacetime ripples as black holes merge, or as is most likely, by using all of the techniques that we now have, together, to probe black holes.

A once exotic concept is now a real working laboratory

As a student, I wondered what to study:particle physics or astrophysics? After reading many popular science articles, my impression was that particle physics had already reached its peak. This field had established an impressive standard model and was able to explain most of the forces and the particles governing our world.

Astronomy though, had just started to explore the depths of a fascinating universe. There was still a lot to be discovered. And I wanted to discover something.

Alla fine, I chose astrophysics as I wanted to understand gravity. And since you find the most extreme gravity near black holes, I decided to stay as close to them as possible.

Oggi, what used to be an exotic concept when I started my studies, promises to become a very real and very much visible physics laboratory in the not too distant future.

Questa storia è stata ripubblicata per gentile concessione di ScienceNordic, la fonte affidabile per le notizie scientifiche in lingua inglese dai paesi nordici. Leggi la storia originale qui.