Credito:Pixabay/CC0 Dominio pubblico

I film spaziali di fantascienza possono fare un pessimo lavoro nell'educare le persone sullo spazio. Nei film, i piloti più accaniti dirigono le loro astronavi da duello attraverso lo spazio come se volassero attraverso un'atmosfera. Si piegano e girano ed eseguono loop e rolls, magari fare un veloce giro di Immelman, come se fossero soggetti alla gravità terrestre. È realistico?

No.

In realtà, è probabile che una battaglia spaziale sembri molto diversa. Con una crescente presenza nello spazio, e il potenziale per futuri conflitti, è tempo di pensare a come sarebbe una vera battaglia spaziale?

La no-profit Aerospace Corporation pensa che sia il momento di considerare come sarebbe una vera battaglia spaziale. La dott.ssa Rebecca Reesman del Center for Space Policy and Strategy della Aerospace Corporation e il suo collega James R. Wilson hanno scritto un documento sul tema delle battaglie spaziali, intitolato "The Physics of Space War:How Orbital Dynamics Constrain Space-to-Space Engagements".

Se le passate vicende umane indicano il futuro, poi procederà la militarizzazione dello spazio. Questo nonostante si parli di mantenere lo spazio pacifico, e nonostante i trattati che dicono lo stesso. Quindi è importante che man mano che più nazioni aumentano la loro presenza nello spazio, e mentre la competizione per le risorse inizia a causare problemi, che la conversazione sul conflitto spaziale prenda una piega realistica.

Questo è il caso che gli autori fanno nell'introduzione al loro articolo. "Mentre gli Stati Uniti e il mondo discutono della possibilità che il conflitto si estenda nello spazio, è importante avere una comprensione generale di ciò che è fisicamente possibile e pratico. Scene da Guerre Stellari, libri e programmi televisivi ritraggono un mondo molto diverso da quello che probabilmente vedremo nei prossimi 50 anni, se mai, date le leggi della fisica."

Una stazione spaziale sovietica Almaz con equipaggio presso il Centro di aviazione e cosmonautica di Mosca. La Russia ha progettato diversi tipi di satelliti militari e stazioni spaziali, alcuni armati di mitra, prima di abbandonare l'idea perché troppo costosa. Credito:di Pulux11 – Opera propria, CC BY-SA 4.0

Non c'è mai stata una battaglia nello spazio ancora. Ma c'è stata qualche attività di test sulle armi. La Cina sta lavorando su armi anti-satellite e ha testato un missile anti-satellite. Così ha l'India. La Russia sta anche lavorando su capacità anti-satellite, e gli Stati Uniti stanno facendo lo stesso. Gli Stati Uniti hanno effettivamente distrutto uno dei propri satelliti con un missile nel 1985.

Questa è probabilmente solo la punta dell'iceberg quando si tratta di futuri conflitti nello spazio. Nessuna di queste attività anti-satellite ha coinvolto persone che viaggiano in veicoli spaziali, e potrebbe non esserci mai bisogno di astronavi militari con equipaggio, secondo la carta. "Gli scontri spazio-spazio in un conflitto moderno sarebbero combattuti esclusivamente con veicoli senza equipaggio controllati da operatori a terra e fortemente vincolati dai limiti che la fisica impone al movimento nello spazio".

Nei primi giorni dell'era spaziale, mentre infuriava ancora la Guerra Fredda, le superpotenze immaginavano che il conflitto nello spazio sarebbe stato in gran parte un'estensione dei conflitti terrestri. I sovietici hanno persino progettato stazioni spaziali armate di mitragliatrice per difendersi dagli attacchi degli astronauti americani. Gli Stati Uniti hanno lavorato su idee simili.

Ma i progressi tecnologici hanno fatto sì che quegli sforzi fossero abbandonati a favore di satelliti senza equipaggio. "Infine, entrambi i programmi vacillarono. Anziché, miglioramenti nella tecnologia e nella trasmissione dei dati, gli stessi sviluppi che alla fine sono alla base della nostra moderna vita connessa, hanno reso possibili satelliti che svolgono le stesse funzioni militari previste per i precedenti programmi con equipaggio". lo spazio è dominato dai satelliti, con solo la ISS che ospita gli umani.

Questo sarà il futuro, secondo la carta. Per i prossimi 50 anni o giù di lì, qualsiasi conflitto nello spazio comporterà attacchi ai satelliti. Ma non tutto sarà un vero e proprio attacco. Gli autori delineano quattro obiettivi in un attacco spaziale:

Le battaglie spaziali saranno probabilmente tra satelliti, e il rifornimento non sarà un'opzione. In questa immagine, un F-16 sta facendo rifornimento da uno Stratotanker KC-135. Credito:dall'aeronautica americana

I satelliti si muovono in modo molto prevedibile. Si muovono velocemente, ma è relativamente facile prevedere la loro posizione futura e intercettarli, in molti casi. Alcuni satelliti possono cambiare la loro altezza orbitale, ma non hanno una reale manovrabilità e quasi nessun modo per evitare un attacco.

"Per descrivere come la fisica limiterebbe gli impegni spazio-spazio, questo documento descrive cinque concetti chiave:i satelliti si muovono rapidamente, i satelliti si muovono in modo prevedibile, lo spazio è grande, il tempismo è tutto, e i satelliti manovrano lentamente."

Il volo attraverso l'atmosfera terrestre non è esattamente semplice, ma è abbastanza intuitivo. Ma nello spazio, è completamente diverso e non è esattamente chiamato volo. Senza atmosfera e bassa gravità, le cose sono molto diverse. "Il movimento nello spazio è controintuitivo per chi è abituato al volo all'interno dell'atmosfera terrestre e alla possibilità di fare rifornimento, " scrivono gli autori.

"Gli impegni spazio-spazio sarebbero deliberati e probabilmente si svolgerebbero lentamente perché lo spazio è grande e le navicelle spaziali possono sfuggire ai loro percorsi prevedibili solo con un grande sforzo. Inoltre, gli attacchi alle risorse spaziali richiederebbero precisione perché i veicoli spaziali e persino le armi terrestri possono ingaggiare bersagli nello spazio solo dopo che calcoli complessi sono stati determinati in un dominio altamente ingegnerizzato." Non ci sarebbero quadri di piloti di caccia in standby, in attesa di arrampicarsi e lanciarsi rapidamente. Anziché, a space battle involving satellites is more of a mathematical exercise.

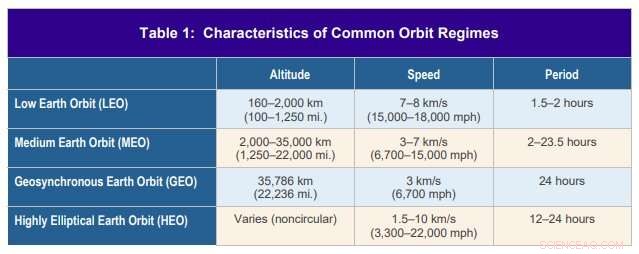

Satellite orbits are predictable and don’t depend on the mass of the satellite. Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020.

"This is true because physics puts constraints on what happens in space. Only by mastering these constraints can other questions such as how to fight and, most importantly, when and why to fight a war in space, be explored, " they write.

A satellite's orbit is predictable because of the relationship between speed, altitude and the orbit's shape. At lower altitudes, satellites can experience atmospheric drag. Anche, the Earth isn't a perfect sphere. But those factors can be accounted for in an attack. "To deviate from their prescribed orbit, satellites must use an engine to maneuver. This contrasts with airplanes, which mostly use air to change direction; the vacuum of space offers no such option, " they write.

The sheer volume of space is also a factor in a space battle. "The volume of space between LEO and GEO is about 200 trillion cubic kilometers (50 trillion cubic miles). That is 190 times bigger than the volume of Earth."

So tracking satellites accurately in that volume of space will be a continuous challenge, since some will be designed to be undetected. But that's not impossible; satellites are regularly tracked. And since they're not very maneuverable, once a satellite's orbit is detected, monitors can keep track of its trajectory.

The sheer volume of space also means that most space battles would be very short-lived. There won't be any dogfights. "Space is big, which means that a space-to-space engagement is not going to be both intense and long. It can only be one or the other:either a short, intense use of a lot of Delta V for big effect or long, deliberate use of Delta V for smaller or persistent effects."

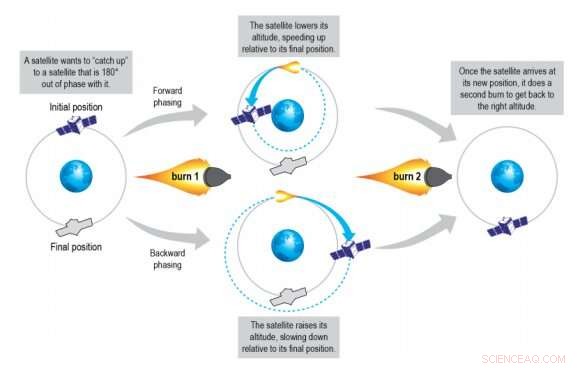

Satellites change their position in their orbit with phasing maneuvers. Any time a satellite raises its orbit, it slows down and appears to be moving backward in relation to its prior orbit and altitude. This is how a satellite can “catch up” to another satellite. Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020

Delta V is a change in velocity, and that requires fuel or propellant. But most satellites don't have the capability to change their velocity, and the few that might are severely fuel-limited.

"Operators of an attack satellite may spend weeks moving a satellite into an attack position during which conditions may have changed that alter the need for or the objective of the attack." And if the defending satellite is able to only slightly change its own path in response to an attack, then the attacking satellite may not have the capability or the fuel to change its own path to intercept it.

The authors also point out that timing is everything. Even if an attacking satellite can orient itself into the same orbital path as its target, there's still no guarantee of proximity.

"The nature of conflict often requires two competing weapons systems to get close to one another, " the report says. The authors use the example of an aircraft carrier needing to get close to its target, and another of jet fighters that also need to be close to each other. The same thing is true of satellites in space.

"Getting two satellites to the same altitude and the same plane is straightforward (though time and ?V consuming), but that does not mean they are yet in the same spot. The phasing—current location along the orbital trajectory—of the two satellites must also be the same. Since speed and altitude are connected, getting two satellites in the same spot is not intuitive." Instead, it takes perfect timing and meticulous preparation.

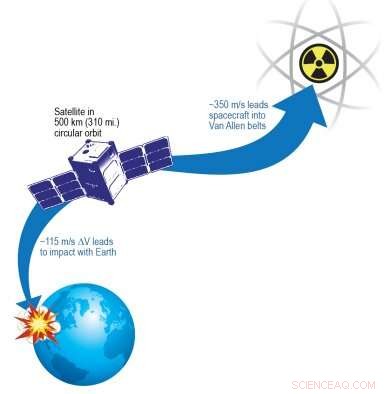

If a satellite performs a forward phasing maneuver with a first burn of 115 m/s or more of ?V, it will reenter Earth’s atmosphere and burn up. Allo stesso modo, if the satellite performs a backward phasing maneuver with a first burn of 350 m/s or more of ?V, it will experience high radiation in the Van Allen belts. These two facts create natural bounds for how quickly a satellite can maneuver in LEO (500 km or 310 mi.). Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020

The authors also discuss another method of approaching a target called "plane matching, " A satellite maneuvers itself so that its orbital plane is aligned with a target. That has the advantage of allowing the attacker to dictate the time of the engagement. "By not initiating threatening maneuvers immediately, an attacker may try to seem harmless while waiting for an optimal time to attack, " the authors explain.

But none of these maneuvers happen quickly. "The physics of space dictate that kinetic space-to-space engagements be deliberate with satellites maneuvering for days, if not weeks or months, beforehand to get into position to have meaningful operational effects, " they write. But it can still be done.

And once the interception has been set up, "…many opportunities can arise to maneuver close enough to engage a target quickly."

There are natural limits to how maneuvering satellites in LEO can do. On one hand, some phasing maneuvers can send the satellite into the Earth's atmosphere where it will be burned up. On the other, it could be sent too far away from LEO, into the Van Allen Belts. So there are constraints on a satellite's maneuverability.

Satellites in geostationary orbits maintain the same relative position over Earth, so some of the mechanics of attacking and defending are different. But overall, the same constraints are still in place. It takes time and energy to maneuver in space, regardless of the type of orbit.

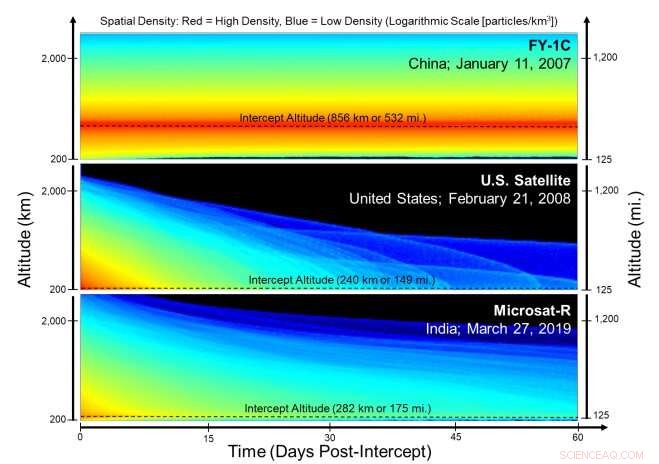

The density of debris is compared at different altitudes as a function of time after the ASAT intercepted (made contact with and destroyed) the target satellite. The Chinese test happened at a much higher altitude (856 km or 532 mi.) than the other two, creating long-lasting debris. Credit:Reesman and Wilson, 2020

But orbital and maneuverability considerations are only a part of what the report addresses.

The authors go on to discuss the types of attacks that can take place. Collisions, projectiles, and electronic jamming or disruption are covered in the paper. Each type has its own considerations and preparations.

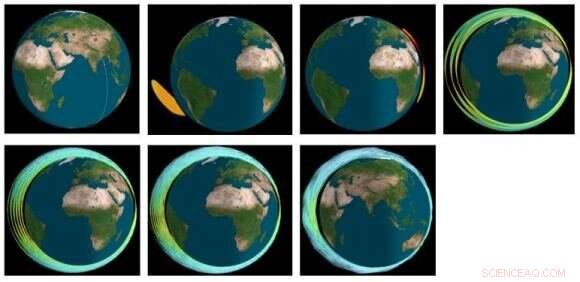

But the authors also discuss the aftermath of some successful attacks:complications arising from debris. Additional debris could end up damaging other unintentional targets, like the attacker's own satellites or those of a neutral nation. There have been three successful anti-satellite attacks:one by China, one by the U.S., and India. The authors prepared a graphic to show the debris from each one.

The debris cloud from an attack is denser immediately after the attack and spreads out quickly. Even though debris density is lowered quickly, the debris spreads out over a larger area and is still hazardous.

The paper is a clear presentation of all of the difficulties with space battles and how much different they would be compared to air-to-air battles. But some other considerations that are still important are outside its scope.

This image shows the debris cloud from the Indian ASAT in 2019. The panels show the cloud at 5 min., 45 min., 90 min., 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, and 6 days after the attack. Credit:Reesman and Wilson 2020

What happens when one nation deduces that their satellites are about to be attacked? They won't sit on their thumbs. They'll likely denounce, threaten, and even retaliate here on Earth. A space attack could end up being a flashpoint for another terrestrial war.

There could end up being an arms race in space, where nations compete to outspend each other on space weaponry and other technology. That's a huge strain on resources for a world that should be focused on meeting the challenge of climate change.

E, where does it all end? War in orbit? War on the moon? War on Mars? When will humanity figure it out and just stop?

Un giorno, maybe, there'll be a final war before we give it all up. But that won't likely be in the next 50 years.

And if there is a war in the next 50 years or so, it may involve satellites, and it may look a lot like how the authors of this report have laid it out:slow, calculated, and deliberate.