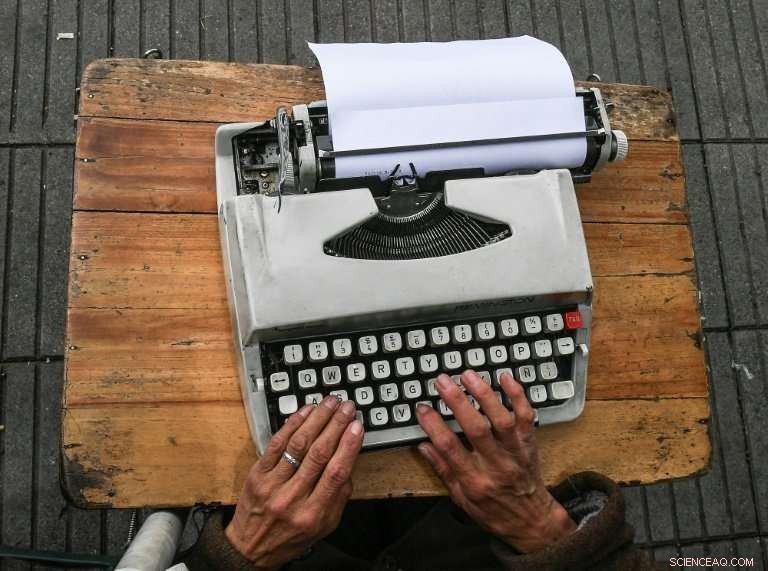

Gli impiegati di strada della Colombia lavorano all'aria aperta con le loro macchine da scrivere appollaiate su un tavolino di fronte a loro

In vista del Primo Maggio, giornalisti dell'Afp, team di video e foto hanno parlato con uomini e donne di tutto il mondo i cui lavori stanno diventando sempre più rari, soprattutto quando la tecnologia trasforma le società.

Gli ultimi impiegati di strada di Bogotà

Inserendo un foglio bianco nel suo Remington Sperry, Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez inizia a scrivere. Uno degli impiegati di strada di Bogotà, ha passato gli ultimi 40 anni a battere a macchina innumerevoli migliaia di documenti.

63 anni, è l'unica donna tra gli impiegati di strada ad aver sistemato i loro minuscoli tavolini sul marciapiede davanti a un moderno edificio di uffici a Bogotà.

Indossando abiti ma senza cravatte, gli scrittori lavorano all'aria aperta, sotto l'ombrellone, seduti su una sedia di plastica con la macchina da scrivere sulle ginocchia.

C'era una volta, questi impiegati svolgevano un ruolo essenziale - con atti pubblici, documenti fiscali e contratti che passano tutti per le loro mani.

Pinilla de Gomez ha imparato il mestiere da suo marito quando sono arrivati nella capitale colombiana negli anni '60. Aveva una fattoria "ma i guerriglieri gliela tolsero, " lei dice.

"A Bogotà, mi ha detto che avrei dovuto imparare a scrivere... ea sillabare. Mi ha insegnato (il lavoro) e poi è morto."

Cesare Diaz, ora 68, si vanta di essere il pioniere di un mestiere che ha finito per diventare un "rifugio" per i pensionati che cercano di ricaricare le loro indennità mensili.

Candelaria Pinilla de Gomez, 63, lavora come impiegato di strada a Bogotà da circa 40 anni

Lavorano dal lunedì al venerdì e guadagnano meno di $280 che è il salario minimo.

Fino ad ora, sono riusciti a sopravvivere praticamente a tutto, tranne forse all'avvento di Internet.

"In questi giorni, una madre chiederà al figlio di scaricare un modulo, compilalo e invialo via internet, " ammette Pinilla de Gomez.

"Questo ci rovina davvero le cose."

— Foto di Luis Acosta. Video di Juan Restrepo

lavandaie, il loro mestiere scompare come il sapone nell'acqua

Le mani di Delia Veloz hanno quasi perso le impronte digitali a causa del costante movimento ritmico di strofinare i vestiti sporchi contro le pietre grezze in una vecchia lavanderia pubblica a Quito.

Con uno straccio di riccioli grigi ricci, questa 74enne è una delle poche persone rimaste in Ecuador che pratica ancora l'antico e impegnativo lavoro di lavandaia, mestiere sempre più raro a causa dell'uso diffuso delle lavatrici domestiche.

Wu Chi-kai piega tubi di vetro spolverati all'interno con polvere fluorescente in forma sopra un potente bruciatore a gas

"Non mi piacciono le lavatrici, non si lavano molto bene. Puoi strofinare meglio le cose a mano, "Veloz dice con orgoglio ad AFP mentre versa un barattolo di acqua gelata delle Ande sopra una giacca.

Da più di cinque decenni lavora all'Ermita, una lavanderia pubblica nel centro coloniale di Quito con la sua pietra rettangolare, serbatoio d'acqua e vari fili per stendere le cose ad asciugare.

Per ogni 12 capi di abbigliamento, guadagna 1,50 dollari (1,20 euro) dai suoi sempre più pochi clienti, soprattutto quelli che non hanno la lavatrice o che preferiscono che le cose vengano lavate a mano.

In un buon giorno, può guadagnare tra $ 3 e $ 6.

A Quito, vi sono ancora almeno cinque lavanderie pubbliche realizzate nella prima metà del XX secolo.

C'è anche chi viene a usare la lavanderia per lavare i propri vestiti o quelli dei propri datori di lavoro, per i quali non si paga.

E una volta al mese, si riuniscono tutti per mantenere i locali puliti e in ordine.

— Foto di Rodrigo Buendia

Il neon è arrivato a definire il paesaggio urbano di Hong Kong, con enormi insegne lampeggianti che sporgono orizzontalmente dai lati degli edifici

Waterboys cominciano a scarseggiare

La mancanza di acqua corrente nei quartieri più poveri del Kenya ha, negli ultimi 18 anni, significava vivere per Sansone Muli, un venditore di acqua nella baraccopoli di Kibera a Nairobi.

"Crescendo volevo essere un uomo d'affari, "dice il 42enne padre di due figli, che fornisce acqua ai macellai, pescherie e ristoranti nell'affollato mercato di Kenyatta.

Vestito con uno spolverino grigio, Muli usa un tubo per riempire la sua serie di taniche cilindriche da 20 litri con l'acqua di tre 10 indipendenti, Serbatoi da 000 litri. Ne carica 15 alla volta su un carrello, e li trasporta ai suoi clienti.

I margini sono minuscoli:Muli compra acqua a cinque scellini ($ 0,05) a lattina e vende a 15, ma può aggiungere fino a 1, 000 scellini al giorno, abbastanza per fare la differenza.

"This job has changed my life because my children are able to go to school and I am able to afford to pay school fees for them, " lui dice.

But Kenya's gradual development and the spreading provision of basic infrastructure, including piped water, means Muli's profitable days are numbered.

— Pictures by Simon Maina. Video by Raphael Ambasu

Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes

Rickshaw pullers fade from India's streets

Mohammad Maqbool Ansari puffs and sweats as he pulls his rickshaw through Kolkata's teeming streets, a veteran of a gruelling trade long outlawed in most parts of the world and slowly fading from India too.

Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life, but Ansari is among a dying breed still eking a living from this back-breaking labour.

The 62-year-old has been pulling rickshaws for nearly four decades, hauling cargo and passengers by hand in drenching monsoon rains and stifling heat that envelops India's heaving eastern metropolis.

Their numbers are declining as pulled rickshaws are relegated to history, usurped by tuk tuks, Kolkata's famous yellow taxis and modern conveniences like Uber.

Ansari cannot imagine life for Kolkata's thousands of rickshaw-wallahs if the job ceased to exist.

"If we don't do it, how will we survive? We can't read or write. We can't do any other work. Once you start, that's it. This is our life, "dice all'Afp.

Sweating profusely on a searing-hot day, his singlet soaked and face dripping, Ansari skilfully weaved his rickshaw through crowded markets and bumper to bumper traffic.

Venezuelan darkroom technician Rodrigo Benavides refuses to go digital

Wearing simple shoes and a chequered sarong, the only real giveaway of his age is a long beard, snow white and frizzy, and a face weathered from a lifetime plying this trade.

Twenty minutes later, he stops, wiping his face on a rag. The passenger offers him a glass of water—a rare blessing—and hands a bill over.

"When it's hot, for a trip that costs 50 rupees ($0.75) I'll ask for an extra 10 rupees. Some will give, some don't, " lui dice.

"But I'm happy with being a rickshaw puller. I'm able to feed myself and my family."

— Pictures by Dibyangshu Sarkar. Video by Atish Patel

Hong Kong's neon nostalgia

Neon sign maker Wu Chi-kai is one of the last remaining craftsmen of his kind in Hong Kong, a city where darkness never really falls thanks to the 24-hour glow of myriad lights.

During his 30 years in the business, neon came to define the urban landscape, huge flashing signs protruding horizontally from the sides of buildings, advertising everything from restaurants to mahjong parlours.

Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography does not exist

But with the growing popularity of brighter LED lights, seen as easier to maintain and more environmentally friendly, and government orders to remove some vintage signs deemed dangerous, the demand for specialists like Chi-kai has dimmed.

Despite a waning client-base, the 50-year-old continues in the trade, working with glass tubes dusted inside with fluorescent powder and containing various gases including neon or argon, as well as mercury, to create different colours.

He bends them into shape over a powerful gas burner at a scorching 1, 000 gradi Celsius.

"Being able to twist straight glass materials into the shape I want, and later to make it glow—it's quite fun, "dice all'Afp, though it is not without risks.

Chi-kai works without a safety visor and has been scalded and cut by glass which sometimes cracks and explodes.

"The painful experiences are the memorable ones, " he adds philosophically.

His father used to scale Hong Kong's famous bamboo scaffolding while installing neon signs across the city.

Believing the installation work too dangerous for his son, he instead encouraged him to learn to make the signs as a teenager. Chi-kai became one of only around 30 masters of the craft in Hong Kong, even in neon's heyday.

Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints

Although demand is now significantly lower than at neon's peak in the 1980s, lui dice, there has been renewed interest and nostalgia for its gentler glow, immortalised in the atmospheric movies of award-winning Hong Kong director Wong Kar-wai.

Some of Chi-kai's clients are now requesting pieces for indoor decoration.

"I've been working with neon lights all my life. I can't think of anything else I'd be better suited for, " lui dice.

— Pictures by Philip Fong. Video by Diana Chan

Developing film as if digital didn't exist

With an ancient 50-year-old Olympus camera and an enlarger that he bought in 1980, Venezuelan photographer Rodrigo Benavides works his "magic" inside a tiny improvised darkroom at home.

Although working with equipment and techniques that have virtually disappeared, he carries on as if digital photography doesn't exist.

"Doesn't interest me at all, " lui dice.

Once upon a time, these clerks played an essential role—with public deeds, tax documents and contracts all passing through their hands

Using his bathroom as a makeshift lab, he develops negatives, turning them into black and white prints. And it still fascinates him every time as the image slowly emerges on coming in to contact with the chemicals.

"I have always tried to be economical with my resources, always have done, always will do, " lui dice, extolling the wonders of his Olympus 35 SP which uses a reel of film, doesn't need batteries and is completely manual.

Born in Caracas 58 years ago, he still remembers the excitement when, at the age of 19, he bought the enlarger in London.

And it was there that he became a keen follower of Group f/64, an influential movement of photographers who championed sharp-focused, unretouched images of natural subjects.

He thinks technology has "upended" photography, turning it into a work of "fiction."

"We have become desensitised to reality, which is much more interesting than fiction, " lui dice.

Some 400 of his pictures taken over 30 years have been compiled into a book on the Venezuelan plains. Others are stacked up in his living room, forming a towering pile, some two meters high.

"They are like my children, " says Benavides, who describes himself as a documentary photographer practising a trade on the verge of extinction.

Delia Veloz, 74, is one of the few people left in Ecuador who still practises the ancient and demanding work of a washerwoman

Washerwomen rub dirty clothes against rough stones at an old public laundry in Quito

In Quito, there are still at least five public laundries which were built in the first half of the 20th century

The lack of running water in Kenya's poorest neighbourhoods has meant a living for Samson Muli, a water seller in Nairobi's Kibera slum

Waterboys supply water to butchers, fishmongers and restaurants in the crowded Kenyatta market

Kolkata is one of the last places on earth where pulled rickshaws still feature in daily life

Mohammad Ashgar is one of the remaining Indian rickshaw pullers undertaking the gruelling trade

© 2018 AFP