Credito:Unsplash/CC0 di dominio pubblico

Gli individui che vivono con il diabete di tipo 1 devono seguire attentamente i regimi di insulina prescritti ogni giorno, ricevendo iniezioni dell'ormone tramite siringa, pompa per insulina o qualche altro dispositivo. E senza trattamenti vitali a lungo termine, questo corso di trattamento è una condanna a vita.

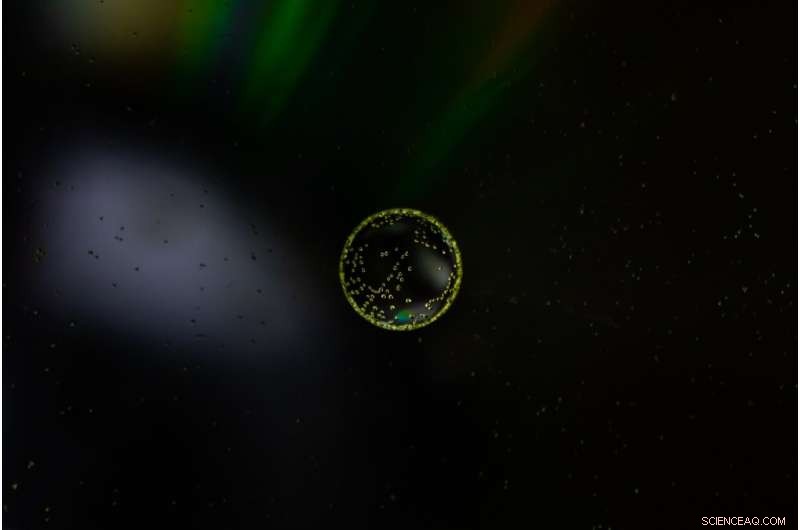

Le isole pancreatiche controllano la produzione di insulina quando i livelli di zucchero nel sangue cambiano e, nel diabete di tipo 1, il sistema immunitario del corpo attacca e distrugge tali cellule produttrici di insulina. Il trapianto di isole è emerso negli ultimi decenni come una potenziale cura per il diabete di tipo 1. Con le isole trapiantate sane, i pazienti con diabete di tipo 1 potrebbero non aver più bisogno di iniezioni di insulina, ma gli sforzi di trapianto hanno subito battute d'arresto poiché il sistema immunitario continua a rifiutare alla fine nuove isole. Gli attuali farmaci immunosoppressori offrono una protezione inadeguata per le cellule e i tessuti trapiantati e sono afflitti da effetti collaterali indesiderati.

Ora un team di ricercatori della Northwestern University ha scoperto una tecnica per contribuire a rendere più efficace l'immunomodulazione. Il metodo utilizza nanocarrier per riprogettare l'immunosoppressore comunemente usato rapamicina. Utilizzando questi nanocarrier caricati con rapamicina, i ricercatori hanno generato una nuova forma di immunosoppressione in grado di colpire cellule specifiche correlate al trapianto senza sopprimere risposte immunitarie più ampie.

L'articolo è stato pubblicato oggi sulla rivista Nature Nanotechnology . Il team della Northwestern è guidato da Evan Scott, il professore di Kay Davis e professore associato di ingegneria biomedica presso la McCormick School of Engineering della Northwestern e microbiologia-immunologia presso la Feinberg School of Medicine della Northwestern University, e Guillermo Ameer, il professore di ingegneria biomedica Daniel Hale Williams presso McCormick e Chirurgia a Feinberg. Ameer è anche direttore del Center for Advanced Regenerative Engineering (CARE).

Specificare l'attacco del corpo

Ameer ha lavorato per migliorare i risultati del trapianto di isole fornendo agli isolotti un ambiente ingegnerizzato, utilizzando biomateriali per ottimizzarne la sopravvivenza e la funzione. Tuttavia, i problemi associati alla tradizionale immunosoppressione sistemica rimangono un ostacolo alla gestione clinica dei pazienti e devono anche essere affrontati per avere un vero impatto sulle loro cure, ha affermato Ameer.

"Questa è stata un'opportunità per collaborare con Evan Scott, leader nell'immunoingegneria, e impegnarsi in una collaborazione di ricerca sulla convergenza che è stata ben eseguita con un'enorme attenzione ai dettagli da Jacqueline Burke, una ricercatrice laureata della National Science Foundation", ha affermato Ameer.

La rapamicina è ben studiata e comunemente usata per sopprimere le risposte immunitarie durante altri tipi di trattamento e trapianti, notevole per la sua vasta gamma di effetti su molti tipi di cellule in tutto il corpo. Tipicamente somministrato per via orale, il dosaggio della rapamicina deve essere attentamente monitorato per prevenire effetti tossici. Tuttavia, a dosi più basse ha scarsa efficacia in casi come il trapianto di isole.

Scott, anche lui membro di CARE, ha affermato di voler vedere come il farmaco potrebbe essere potenziato inserendolo in una nanoparticella e "controllando dove va all'interno del corpo".

"Per evitare gli ampi effetti della rapamicina durante il trattamento, il farmaco viene generalmente somministrato a bassi dosaggi e tramite vie di somministrazione specifiche, principalmente per via orale", ha affermato Scott. "But in the case of a transplant, you have to give enough rapamycin to systemically suppress T cells, which can have significant side effects like hair loss, mouth sores and an overall weakened immune system."

Following a transplant, immune cells, called T cells, will reject newly introduced foreign cells and tissues. Immunosuppressants are used to inhibit this effect but can also impact the body's ability to fight other infections by shutting down T cells across the body. But the team formulated the nanocarrier and drug mixture to have a more specific effect. Instead of directly modulating T cells—the most common therapeutic target of rapamycin—the nanoparticle would be designed to target and modify antigen presenting cells (APCs) that allow for more targeted, controlled immunosuppression.

Using nanoparticles also enabled the team to deliver rapamycin through a subcutaneous injection, which they discovered uses a different metabolic pathway to avoid extensive drug loss that occurs in the liver following oral administration. This route of administration requires significantly less rapamycin to be effective—about half the standard dose.

"We wondered, can rapamycin be re-engineered to avoid non-specific suppression of T cells and instead stimulate a tolerogenic pathway by delivering the drug to different types of immune cells?" Scott said. "By changing the cell types that are targeted, we actually changed the way that immunosuppression was achieved."

A 'pipe dream' come true in diabetes research

The team tested the hypothesis on mice, introducing diabetes to the population before treating them with a combination of islet transplantation and rapamycin, delivered via the standard Rapamune oral regimen and their nanocarrier formulation. Beginning the day before transplantation, mice were given injections of the altered drug and continued injections every three days for two weeks.

The team observed minimal side effects in the mice and found the diabetes was eradicated for the length of their 100-day trial; but the treatment should last the transplant's lifespan. The team also demonstrated the population of mice treated with the nano-delivered drug had a "robust immune response" compared to mice given standard treatments of the drug.

The concept of enhancing and controlling side effects of drugs via nanodelivery is not a new one, Scott said. "But here we're not enhancing an effect, we are changing it—by repurposing the biochemical pathway of a drug, in this case mTOR inhibition by rapamycin, we are generating a totally different cellular response."

The team's discovery could have far-reaching implications. "This approach can be applied to other transplanted tissues and organs, opening up new research areas and options for patients," Ameer said. "We are now working on taking these very exciting results one step closer to clinical use."

Jacqueline Burke, the first author on the study and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow and researcher working with Scott and Ameer at CARE, said she could hardly believe her readings when she saw the mice's blood sugar plummet from highly diabetic levels to an even number. She kept double-checking to make sure it wasn't a fluke, but saw the number sustained over the course of months.

Research hits close to home

For Burke, a doctoral candidate studying biomedical engineering, the research hits closer to home. Burke is one such individual for whom daily shots are a well-known part of her life. She was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when she was nine, and for a long time knew she wanted to somehow contribute to the field.

"At my past program, I worked on wound healing for diabetic foot ulcers, which are a complication of Type 1 diabetes," Burke said. "As someone who's 26, I never really want to get there, so I felt like a better strategy would be to focus on how we can treat diabetes now in a more succinct way that mimics the natural occurrences of the pancreas in a non-diabetic person."

The all-Northwestern research team has been working on experiments and publishing studies on islet transplantation for three years, and both Burke and Scott say the work they just published could have been broken into two or three papers. What they've published now, though, they consider a breakthrough and say it could have major implications on the future of diabetes research.

Scott has begun the process of patenting the method and collaborating with industrial partners to ultimately move it into the clinical trials stage. Commercializing his work would address the remaining issues that have arisen for new technologies like Vertex's stem-cell derived pancreatic islets for diabetes treatment.

The paper is titled "Subcutaneous nanotherapy repurposes the immunosuppressive mechanism of rapamycin to enhance allogeneic islet graft viability." + Esplora ulteriormente