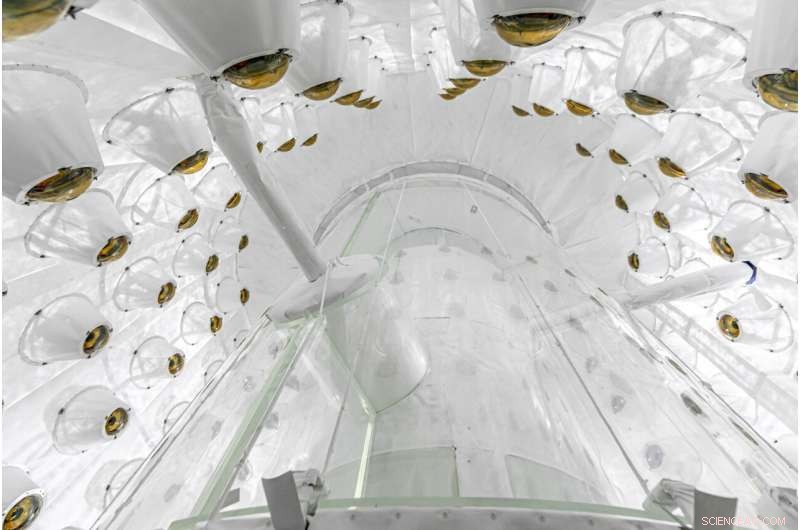

Membri del team LZ nel serbatoio dell'acqua LZ dopo l'installazione del rilevatore esterno. Credito:Matthew Kapust/struttura di ricerca sotterranea di Sanford

Nelle profondità delle Black Hills del South Dakota nella Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF), un rilevatore di materia oscura innovativo e dalla sensibilità unica, l'esperimento LUX-ZEPLIN (LZ), guidato dal Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (Berkeley Lab), ha superato un fase di verifica delle operazioni di avvio e consegna dei primi risultati.

Il messaggio da portare a casa di questa startup di successo:"Siamo pronti e tutto sembra a posto", ha affermato Kevin Lesko, fisico senior del Berkeley Lab ed ex portavoce di LZ. "È un rilevatore complesso con molte parti e funzionano tutti bene secondo le aspettative", ha affermato.

In un documento pubblicato online oggi sul sito Web dell'esperimento, i ricercatori di LZ riferiscono che con la corsa iniziale, LZ è già il rilevatore di materia oscura più sensibile al mondo. Il documento apparirà nell'archivio di prestampa online arXiv.org più tardi oggi. Il portavoce di LZ Hugh Lippincott dell'Università della California Santa Barbara ha dichiarato:"Abbiamo in programma di raccogliere circa 20 volte più dati nei prossimi anni, quindi siamo solo all'inizio. C'è molta scienza da fare ed è molto eccitante". /P>

Le particelle di materia oscura non sono mai state effettivamente rilevate, ma forse non per molto. Il conto alla rovescia potrebbe essere iniziato con i risultati dei primi 60 "giorni live" di test di LZ. Questi dati sono stati raccolti in un arco di tre mesi e mezzo di operazioni iniziali a partire dalla fine di dicembre. Questo è stato un periodo abbastanza lungo da confermare che tutti gli aspetti del rilevatore funzionavano bene.

Invisibile, poiché non emette, assorbe o disperde la luce, la presenza della materia oscura e l'attrazione gravitazionale sono comunque fondamentali per la nostra comprensione dell'universo. Ad esempio, la presenza di materia oscura, stimata in circa l'85 per cento della massa totale dell'universo, modella la forma e il movimento delle galassie, ed è invocata dai ricercatori per spiegare cosa si sa sulla struttura e l'espansione su larga scala dell'universo.

Guardando verso il rivelatore esterno LZ, usato per porre il veto alla radioattività che può simulare un segnale di materia oscura. Credito:Matthew Kapust/struttura di ricerca sotterranea di Sanford

Il cuore del rivelatore di materia oscura LZ è costituito da due serbatoi di titanio annidati riempiti con dieci tonnellate di xeno liquido purissimo e visualizzati da due array di tubi fotomoltiplicatori (PMT) in grado di rilevare deboli sorgenti di luce. I serbatoi di titanio risiedono in un sistema di rilevamento più ampio per catturare particelle che potrebbero imitare un segnale di materia oscura.

"I'm thrilled to see this complex detector ready to address the long-standing issue of what dark matter is made of," said Berkeley Lab Physics Division Director Nathalie Palanque-Delabrouille. "The LZ team now has in hand the most ambitious instrument to do so."

The design, manufacturing, and installation phases of the LZ detector were led by Berkeley Lab project director Gil Gilchriese in conjunction with an international team of 250 scientists and engineers from over 35 institutions from the US, UK, Portugal, and South Korea. The LZ operations manager is Berkeley Lab's Simon Fiorucci. Together, the collaboration is hoping to use the instrument to record the first direct evidence of dark matter, the so-called missing mass of the cosmos.

Henrique Araújo, from Imperial College London, leads the UK groups and previously the last phase of the UK-based ZEPLIN-III program. He worked very closely with the Berkeley team and other colleagues to integrate the international contributions. "We started out with two groups with different outlooks and ended up with a highly tuned orchestra working seamlessly together to deliver a great experiment," Araújo said.

An underground detector

Tucked away about a mile underground at SURF in Lead, S.D., LZ is designed to capture dark matter in the form of weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs). The experiment is underground to protect it from cosmic radiation at the surface that could drown out dark matter signals.

(Left) A schematic of the LZ detector. (Right) Illustration of LZ operation—particles interact in liquid xenon, releasing a flash of light and charge that are collected by photomultiplier tube arrays at top and bottom. Credit:Left schematic:LZ collaboration. Right image:LZ/SLAC

Particle collisions in the xenon produce visible scintillation or flashes of light, which are recorded by the PMTs, explained Aaron Manalaysay from Berkeley Lab, who as physics coordinator, led the collaboration's efforts to produce these first physics results. "The collaboration worked well together to calibrate and to understand the detector response," Manalaysay said. "Considering we just turned it on a few months ago and during COVID restrictions, it is impressive we have such significant results already."

The collisions will also knock electrons off xenon atoms, sending them to drift to the top of the chamber under an applied electric field where they produce another flash permitting spatial event reconstruction. The characteristics of the scintillation help determine the types of particles interacting in the xenon.

Mike Headley, executive director of SURF Lab, said, "The entire SURF team congratulates the LZ Collaboration in reaching this major milestone. The LZ team has been a wonderful partner and we're proud to host them at SURF."

Fiorucci said the onsite team deserves special praise at this startup milestone, given that the detector was transported underground late in 2019, just before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. He said with travel severely restricted, only a few LZ scientists could make the trip to help on site. The team in South Dakota took excellent care of LZ.

"I'd like to second the praise for the team at SURF and would also like to express gratitude to the large number of people who provided remote support throughout the construction, commissioning and operations of LZ, many of whom worked full time from their home institutions making sure the experiment would be a success and continue to do so now," said Tomasz Biesiadzinski of SLAC, the LZ detector operations manager.

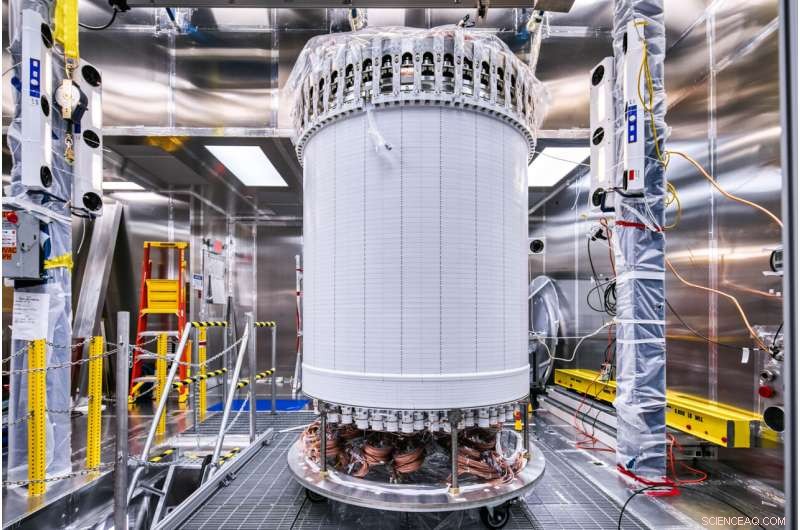

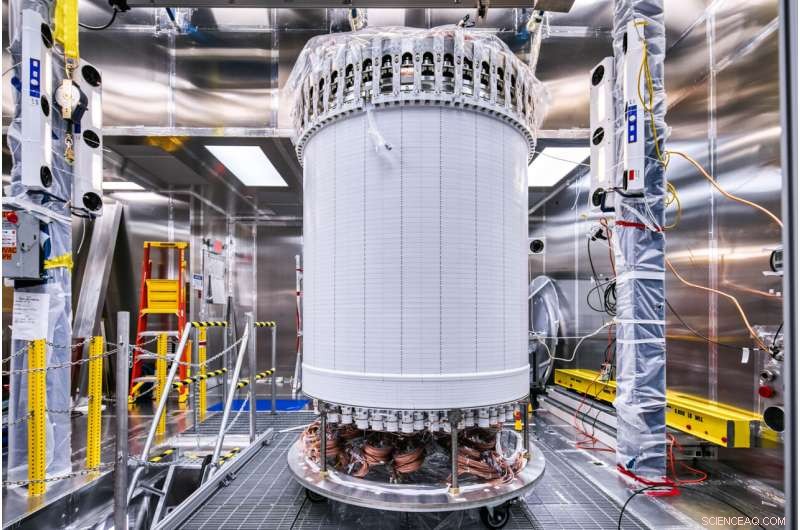

The LZ central detector in the clean room at Sanford Underground Research Facility after assembly, before beginning its journey underground. Credit:Matthew Kapust, Sanford Underground Research Facility

"Lots of subsystems started to come together as we started taking data for detector commissioning, calibrations and science running. Turning on a new experiment is challenging, but we have a great LZ team that worked closely together to get us through the early stages of understanding our detector," said David Woodward from Pennsylvania State University, who coordinates the detector run planning.

Maria Elena Monzani of SLAC, the Deputy Operations Manager for Computing and Software, said, "We had amazing scientists and software developers throughout the collaboration, who tirelessly supported data movement, data processing, and simulations, allowing for a flawless commissioning of the detector. The support of NERSC [National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center] was invaluable."

With confirmation that LZ and its systems are operating successfully, Lesko said, it is time for full-scale observations to begin in hopes that a dark matter particle will collide with a xenon atom in the LZ detector very soon. + Esplora ulteriormente