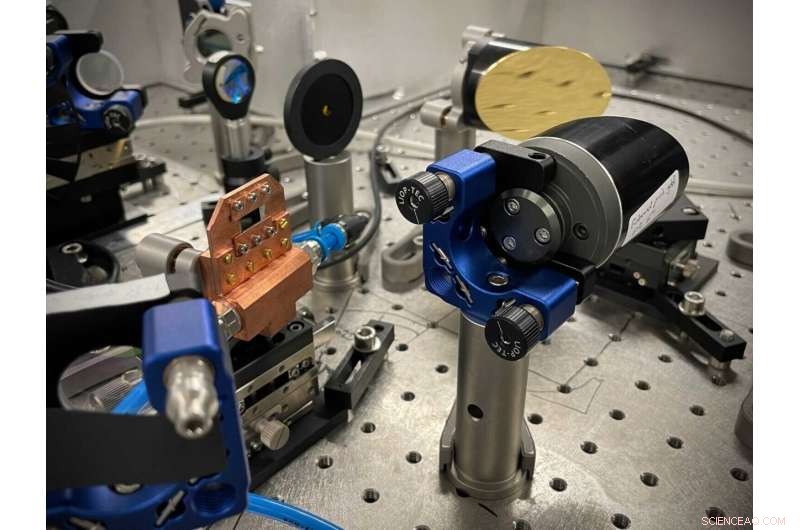

I nanosheet a semiconduttore nel supporto in rame raffreddato ad acqua trasformano un impulso laser a infrarossi in un impulso terahertz effettivamente unipolare. Il team afferma che il loro emettitore di terahertz potrebbe essere fatto per stare all'interno di una scatola di fiammiferi. Credito:Christian Meineke, Huber Lab, Università di Ratisbona

Un impulso laser che elude la simmetria intrinseca delle onde luminose potrebbe manipolare le informazioni quantistiche, avvicinandoci potenzialmente al calcolo quantistico a temperatura ambiente.

Lo studio, condotto da ricercatori dell'Università di Regensburg e dell'Università del Michigan, potrebbe anche accelerare l'elaborazione convenzionale.

L'informatica quantistica ha il potenziale per accelerare le soluzioni a problemi che devono esplorare molte variabili contemporaneamente, tra cui la scoperta di farmaci, le previsioni meteorologiche e la crittografia per la sicurezza informatica. I bit di computer convenzionali codificano 1 o 0, ma i bit quantistici, o qubit, possono codificare entrambi contemporaneamente. Ciò consente essenzialmente ai computer quantistici di lavorare su più scenari contemporaneamente, piuttosto che esplorarli uno dopo l'altro. Tuttavia, questi stati misti non durano a lungo, quindi l'elaborazione delle informazioni deve essere più veloce di quanto i circuiti elettronici possano raccogliere.

Mentre gli impulsi laser possono essere utilizzati per manipolare gli stati energetici dei qubit, sono possibili diversi modi di calcolo se i portatori di carica utilizzati per codificare le informazioni quantistiche possono essere spostati, incluso un approccio a temperatura ambiente. La luce terahertz, che si trova tra la radiazione infrarossa e quella a microonde, oscilla abbastanza velocemente da fornire la velocità, ma anche la forma dell'onda è un problema. Vale a dire, le onde elettromagnetiche sono obbligate a produrre oscillazioni sia positive che negative, che si sommano a zero.

Il ciclo positivo può spostare portatori di carica, come gli elettroni. Ma poi il ciclo negativo riporta le cariche al punto in cui erano iniziate. Per controllare in modo affidabile le informazioni quantistiche, è necessaria un'onda luminosa asimmetrica.

"L'ottimale sarebbe un'"onda" completamente direzionale e unipolare, quindi ci sarebbe solo il picco centrale, nessuna oscillazione. Questo sarebbe il sogno. Ma la realtà è che i campi di luce che si propagano devono oscillare, quindi cerchiamo di fare the oscillations as small as we can," said Mackillo Kira, U-M professor of electrical engineering and computer science and leader of the theory aspects of the study in Light:Science &Applications .

Since waves that are only positive or only negative are physically impossible, the international team came up with a way to do the next best thing. They created an effectively unipolar wave with a very sharp, high-amplitude positive peak flanked by two long, low-amplitude negative peaks. This makes the positive peak forceful enough to move charge carriers while the negative peaks are too small to have much effect.

They did this by carefully engineering nanosheets of a gallium arsenide semiconductor to design the terahertz emission through the motion of electrons and holes, which are essentially the spaces left behind when electrons move in semiconductors. The nanosheets, each about as thick as one thousandth of a hair, were made in the lab of Dominique Bougeard, a professor of physics at the University of Regensburg in Germany.

Then, the group of Rupert Huber, also a professor of physics at the University of Regensburg, stacked the semiconductor nanosheets in front of a laser. When the near-infrared pulse hit the nanosheet, it generated electrons. Due to the design of the nanosheets, the electrons welcomed separation from the holes, so they shot forward. Then, the pull from the holes drew the electrons back. As the electrons rejoined the holes, they released the energy they'd picked up from the laser pulse as a strong positive terahertz half-cycle preceded and followed by a weak, long negative half-cycle.

"The resulting terahertz emission is stunningly unipolar, with the single positive half-cycle peaking about four times higher than the two negative ones," Huber said. "We have been working for many years on light pulses with fewer and fewer oscillation cycles. The possibility of generating terahertz pulses so short that they effectively comprise less than a single half-oscillation cycle was beyond our bold dreams."

Next, the team intends to use these pulses to manipulate electrons in room temperature quantum materials, exploring mechanisms for quantum information processing. The pulses could also be used for ultrafast processing of conventional information.

"Now that we know the key factor of unipolar pulses, we may be able to shape terahertz pulses to be even more asymmetric and tailored for controlling semiconductor qubits," said Qiannan Wen, a Ph.D. student in applied physics at U-M and a co-first-author of the study, along with Christian Meineke and Michael Prager, Ph.D. students in physics at the University of Regensburg. + Esplora ulteriormente