Illustrazione della sonda solare Parker che si avvicina al sole. Credito: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben

Al centro della comprensione del nostro ambiente spaziale c'è la conoscenza che le condizioni in tutto lo spazio, dal sole alle atmosfere dei pianeti all'ambiente delle radiazioni nello spazio profondo, sono collegate.

Studiare questa connessione, un campo della scienza chiamato eliofisica, è un compito complesso:i ricercatori seguono improvvise eruzioni di materiale, radiazione, e particelle sullo sfondo dell'onnipresente deflusso di materiale solare.

Una confluenza di eventi all'inizio del 2020 ha creato un laboratorio spaziale quasi ideale, combinando l'allineamento di alcuni dei migliori osservatori dell'umanità, tra cui Parker Solar Probe, durante il suo quarto sorvolo solare, con un periodo di quiete nell'attività del sole, quando è più facile studiare quelle condizioni di fondo. Queste condizioni hanno fornito un'opportunità unica per gli scienziati di esaminare come il sole influenza le condizioni in punti dello spazio, con molteplici angoli di osservazione e a diverse distanze dal sole.

Il sole è una stella attiva il cui campo magnetico è diffuso in tutto il sistema solare, trasportato all'interno del flusso costante di materiale del sole chiamato vento solare. Colpisce i veicoli spaziali e modella gli ambienti dei mondi in tutto il sistema solare. Abbiamo osservato il sole, spazio vicino alla Terra e ad altri pianeti, e anche i bordi più distanti della sfera d'influenza del sole per decenni. E il 2018 ha segnato il lancio di un nuovo, osservatorio rivoluzionario:Parker Solar Probe, con un piano per volare a circa 3,83 milioni di miglia dalla superficie visibile del sole.

Parker ha avuto quattro incontri ravvicinati del sole. (I dati dei primi incontri di Parker con il sole hanno già rivelato una nuova immagine della sua atmosfera.) Durante il suo quarto incontro solare, tra gennaio e febbraio 2020, la navicella è passata direttamente tra il sole e la Terra. Ciò ha offerto agli scienziati un'opportunità unica:il vento solare misurato da Parker Solar Probe quando era più vicino al sole avrebbe giorni dopo, arrivare sulla Terra, dove il vento stesso e i suoi effetti potevano essere misurati sia da veicoli spaziali che da osservatori a terra. Per di più, gli osservatori solari sopra e vicino alla Terra avrebbero una visione chiara delle posizioni sul sole che hanno prodotto il vento solare misurato da Parker Solar Probe.

"Sappiamo dai dati di Parker che ci sono alcune strutture che hanno origine sulla o vicino alla superficie solare. Dobbiamo guardare le regioni di origine di queste strutture per comprendere appieno come si formano, evolvere, e contribuiscono alla dinamica del plasma nel vento solare, " disse Nour Raouafi, scienziato del progetto per la missione Parker Solar Probe presso il Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory a Laurel, Maryland. "Gli osservatori terrestri e altre missioni spaziali forniscono osservazioni di supporto che possono aiutare a disegnare il quadro completo di ciò che Parker sta osservando".

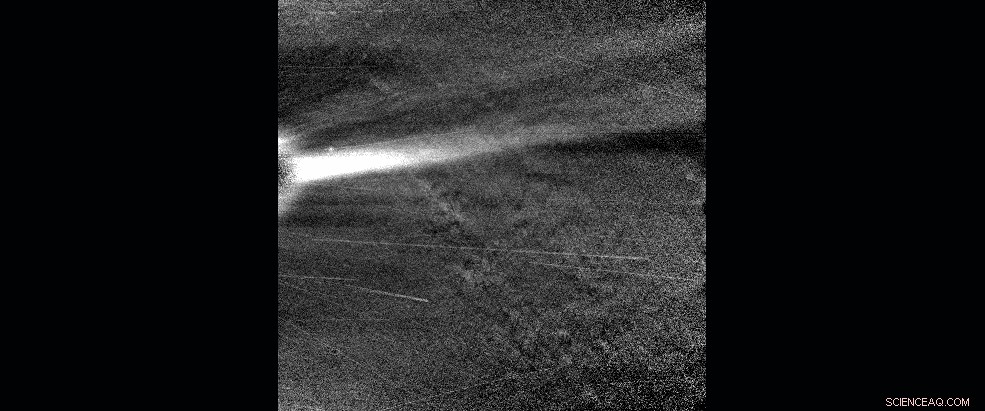

Questa sequenza animata di immagini a luce visibile dello strumento WISPR di Parker Solar Probe mostra uno streamer coronale, osservato quando Parker Solar Probe era vicino al perielio il 28 gennaio, 2020. Credito:NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Laboratorio di ricerca navale/Parker Solar Probe

Questo allineamento celeste sarebbe di interesse per gli scienziati in qualsiasi circostanza, ma coincise anche con un altro periodo astronomico di interesse per gli scienziati:il minimo solare. Questo è il punto durante il sole regolare, cicli di attività di circa 11 anni quando l'attività solare è al suo livello più basso, quindi eruzioni improvvise sul sole come i brillamenti solari, le espulsioni di massa coronale e gli eventi di particelle energetiche sono meno probabili. E questo significa che studiare il sole vicino al minimo solare è un vantaggio per gli scienziati che possono osservare un sistema più semplice e quindi districare quali eventi causano quali effetti.

"Questo periodo fornisce le condizioni perfette per tracciare il vento solare dal sole alla Terra e ai pianeti, " disse Giuliana de Toma, uno scienziato solare presso l'Osservatorio d'alta quota a Boulder, Colorado, che ha guidato il coordinamento tra gli osservatori per questa campagna di osservazione. "È un momento in cui possiamo seguire più facilmente il vento solare, visto che non abbiamo perturbazioni dal sole."

Per decenni, gli scienziati hanno raccolto osservazioni durante questi periodi di minimo solare, uno sforzo co-guidato da Sarah Gibson, uno scienziato solare presso l'Osservatorio d'alta quota, e altri scienziati. Per ciascuno degli ultimi tre periodi di minimo solare, gli scienziati hanno raccolto osservazioni da un elenco in continua espansione di osservatori nello spazio e a terra, sperando che la ricchezza di dati sul vento solare indisturbato sveli nuove informazioni su come si forma e si evolve. Per questo periodo di minimo solare, gli scienziati hanno iniziato a raccogliere osservazioni coordinate a partire dall'inizio del 2019 sotto l'ombrello Whole Heliosphere and Planetary Interactions, o WHPI in breve.

Questa particolare campagna WHPI comprendeva una serie di osservazioni più ampia che mai:coprendo non solo il sole e gli effetti sulla Terra, ma anche i dati raccolti su Marte e la natura dello spazio in tutto il sistema solare, il tutto in accordo con il quarto e più vicino sorvolo del sole di Parker Solar Probe.

Gli organizzatori del WHPI hanno riunito osservatori da tutto il mondo e oltre. La combinazione di dati provenienti da dozzine di osservatori sulla Terra e nello spazio offre agli scienziati la possibilità di dipingere quello che potrebbe essere il quadro più completo di sempre del vento solare:dalle immagini della sua nascita con i telescopi solari, ai campioni poco dopo aver lasciato il sole con Parker Solar Probe, a osservazioni multipunto del suo stato mutevole nello spazio.

Continua a leggere per vedere campioni dei tipi di dati acquisiti durante questa collaborazione internazionale di osservatori solari e spaziali.

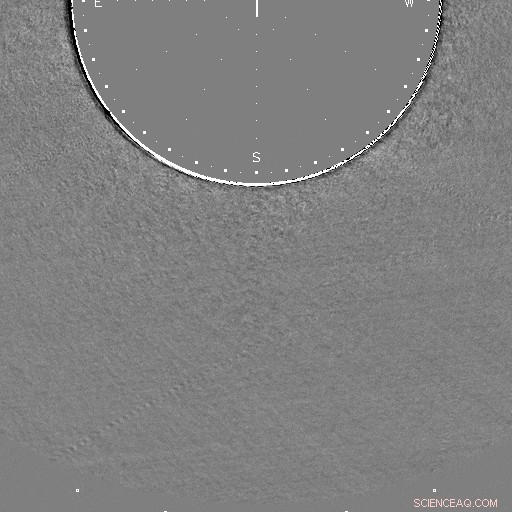

I dati dell'Osservatorio solare di Mauna Loa alle Hawaii mostrano un getto di materiale espulso vicino al polo sud del Sole il 21 gennaio, 2020 (UTC). Questa immagine differenza viene creata sottraendo i pixel dell'immagine precedente dall'immagine corrente per evidenziare le modifiche. Credito:Osservatorio solare di Mauna Loa/K-Cor

Sonda solare Parker

I primi dati del passaggio vicino al sole di Parker Solar Probe durante la campagna WHPI mostrano un sistema eolico solare più dinamico di quello che è visibile nelle osservazioni vicino alla Terra. In particolare, gli scienziati sperano che l'intero set di dati, collegato alla Terra nel maggio 2020, rivelerà strutture dinamiche, come minuscole espulsioni di massa coronale e corde di flusso magnetico nelle loro prime fasi di sviluppo, che non può essere visto con altri osservatori che guardano da più lontano. Strutture di collegamento come questa, prima troppo piccolo o troppo lontano per vedere, con il vento solare e le misurazioni vicine alla Terra possono aiutare gli scienziati a capire meglio come cambia il vento solare durante la sua vita e come le sue origini vicino al sole influenzano il suo comportamento in tutto il sistema solare.

Osservatorio solare di Mauna Loa

Le viste ravvicinate delle strutture del vento solare di Parker Solar Probe sono integrate da osservatori solari sulla Terra e nello spazio, che hanno un campo visivo più ampio per catturare le strutture del vento solare.

I dati dell'Osservatorio solare di Mauna Loa alle Hawaii mostrano un getto di materiale espulso vicino al polo sud del sole il 21 gennaio. 2020. I getti coronali come questo sono una caratteristica del vento solare che gli scienziati sperano di osservare più da vicino con Parker Solar Probe, poiché i meccanismi che li creano potrebbero far luce sulla nascita e sull'accelerazione del vento solare.

"Sarebbe estremamente fortunato se Parker Solar Probe osservasse questo getto, since it would provide information on plasma and the field in and around the jet not long after its formation, " said Joan Burkepile, lead scientist for the Coronal Solar Magnetism Observatory K-coronagraph instrument at the Mauna Loa Solar Observatory, which captured these images.

Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory

Along with observations of the solar wind from Parker Solar Probe and near Earth, scientists also have detailed images of the sun and its atmosphere from spacecraft like NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory and the Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory. NASA's Solar and Terrestrial Relations Observatory, or STEREO, has a distinct view of the sun from its vantage point about 78 degrees away from Earth.

During this WHPI campaign, scientists took advantage of this unique viewing angle. From Jan. 21-23—when Parker Solar Probe and STEREO were aligned—the STEREO mission team increased the exposure length and frequency of images taken by its coronagraph, revealing fine structures in the solar wind as they speed out from the sun.

These difference images are created by subtracting the pixels of a previous image from the current image to highlight changes—here, revealing a small CME that would otherwise be difficult to see.

The Solar Dynamics Observatory, or SDO, takes high-resolution views of the entire sun, revealing fine details on the solar surface and the lower solar atmosphere. These images were captured in a wavelength of extreme ultraviolet light at 171 Angstroms, highlighting the quiet parts of the sun's outer atmosphere, the corona. This data—along with SDO's images in other wavelengths—maps much of the sun's activity, allowing scientists to connect solar wind measurements from Parker Solar Probe and other spacecraft with their possible origins on the sun.

Modeling the Data

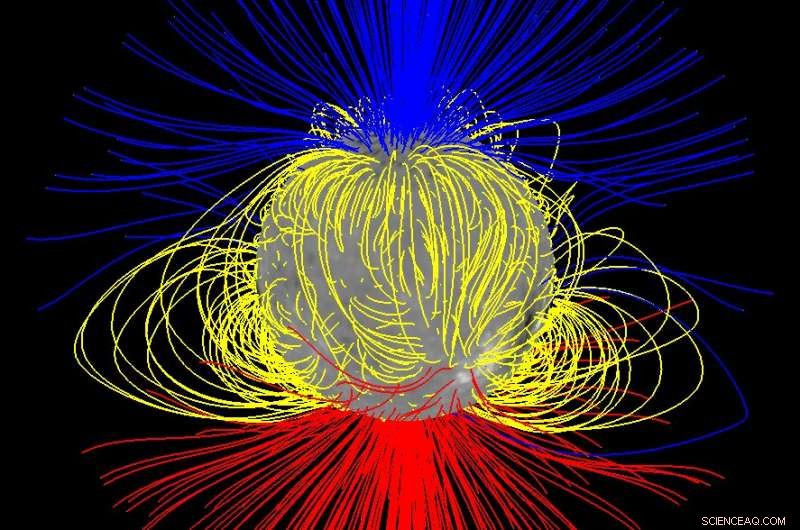

Ideally, scientists could use these images to readily pinpoint the region on the sun that produced a particular stream of solar wind measured by Parker Solar Probe—but identifying the source of any given solar wind stream observed by a spacecraft is not simple. Generalmente, the magnetic field lines that guide the solar wind's movement flow out of the Northern half of the sun point in the opposite direction than they do in the Southern half. In early 2020, Parker Solar Probe's position was right at the boundary between the two—an area known as the heliospheric current sheet.

"For this perihelion, Parker Solar Probe was very close to the current sheet, so a little nudge one way or the other would make the magnetic footpoint shift to the south or north pole, " said Nick Arge, a solar scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "We were on the tipping point where sometimes it went north, sometimes south."

Predicting which side of the tipping point Parker Solar Probe was on was the responsibility of the modeling teams. Using what we know about the sun's magnetic field and the clues we can glean from distant images of the sun, they made day-by-day predictions of where, precisely, on the sun birthed the solar wind that Parker would fly through on a given day. Several modeling groups made daily attempts to answer just that question.

Using measurements of the magnetic field at the sun's surface, each group made a daily prediction for the source region producing the solar wind that Parker Solar Probe was flying through.

Arge worked with Shaela Jones, a solar scientist at NASA Goddard who did daily forecasting during the WHPI campaign, using a model originally developed by Arge and colleagues Yi-Ming Wang and Neil Sheeley, called the WSA model. According to their forecasts, the predicted source of the solar wind switched between hemispheres suddenly during the observation campaign, because Earth's orbit at the time was also closely aligned with the heliospheric current sheet—that region where the direction of magnetic polarity and the source of the solar wind switches between north and south. They predicted that Parker Solar Probe, flying in a similar plane as Earth, would experience similar switches in solar wind source and magnetic polarity as it flew near the sun.

Solar wind models rely on daily measurements of the sun's surface magnetic field—the black and white image underlaid. This particular model used measurements from the National Solar Observatory's Global Oscillation Network Group and a model that focuses on predicting how the sun's surface magnetic field will change over several days. Creating these magnetic surface maps is a complicated and imperfect process unto itself, and some of the modeling groups participating in the WHPI campaign also used magnetic measurements from multiple observatories. Questo, along with differences in each group's models, created a spread of predictions that sometimes placed the source of Parker Solar Probe's solar wind stream in two different hemispheres of the sun. But given the inherent uncertainty in modeling the solar wind's source, these different predictions can actually make for more robust operations.

The sun's "open" magnetic field — shown in this model in blue and red, with looped or closed field shown in yellow — primarily comes from near the Sun's north and south poles during solar minimum, but it spreads out to fill space converging near the Sun's equator. Credit:NASA/Nick Arge

"If you can observe the sun in two different places with two telescopes, you have a better chance to get the right spot, " ha detto Jones.

Poker Flat Incoherent Scatter Radar

The solar wind carries with it both an enormous amount of energy and the embedded magnetic field of the sun. When it reaches Earth, it can ring our planet's natural magnetic field like a bell, making it bend and deform—which produces a measurable change in magnetic field strength at certain points on Earth's surface. We track those changes because magnetic field oscillations can lead to a host of space weather effects that interfere with spacecraft or even, occasionally, utility grids on the ground.

A host of ground-based magnetometers have tracked these effects since the 1850s, and they're one of the many sets of data scientists are gathering in connection with this campaign. Other ground-based instruments can reveal the invisible effects of space weather in our atmosphere. One such system is the Poker Flat Incoherent Scatter Radar, or PFISR—a radar system based at the Poker Flat Research Range near Fairbanks, dell'Alaska.

This radar is specially tuned to detect one of most reliable indicators of a disturbance in Earth's magnetic field:electrons in Earth's upper atmosphere. These electrons are created when particles trapped in the magnetosphere are sent zooming into Earth's atmosphere by a complex series of events, a set of circumstances known as a magnetospheric substorm.

On Jan. 16, PFISR measured the changing electrons in Earth's upper atmosphere during one such substorm. During a substorm, particles cascade into the upper atmosphere, not only creating the shower of electrons measured by the radar, but driving a more visible effect:the aurora. PFISR uses multiple beams of radar oriented in different directions, which allowed scientists to build up a three-dimensional picture of how electrons in the atmosphere changed throughout the substorm.

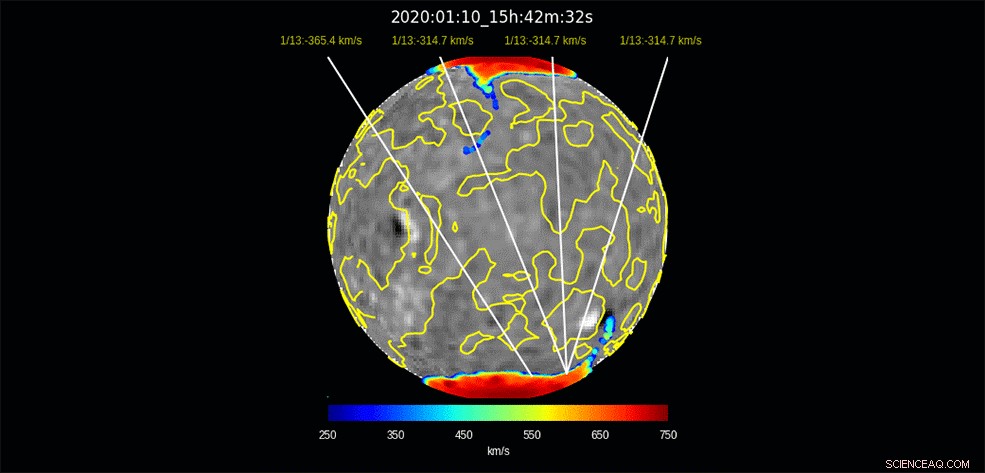

This model run — produced by Nick Arge and Shaela Jones using the WSA model — illustrates the predicted origin for solar wind that will impact Earth days later, spanning Jan. 10 – Feb. 3, 2020. The colored regions near the sun's north and south poles show the regions from which the solar wind flows out, with red regions showing a faster flow and blue regions showing a slower flow. The yellow lines on the sun divide areas of opposite magnetic polarity. The white lines indicate the predicted points of origin for the solar wind arriving at Earth at the given date. The black and white underlaid image shows a map of the magnetic field at the sun's surface, the basis for the model's predictions. The black regions are where the magnetic field points inward, toward the sun, and white regions are where the field points outward, away from the sun. Credit:NASA/Nick Arge/Shaela Jones

Because this substorm took place so early in the observation campaign—only one day after data collection began—it's unlikely that it was caused by conditions on the sun observed during the campaign. Ma anche così, the connection between magnetospheric substorms and the broader, global-scale effects created by the solar wind—called geomagnetic storms—isn't entirely understood.

"This substorm didn't happen during a geomagnetic storm time, " said Roger Varney, principal investigator for PFISR at SRI International in Menlo Park, California. "The solar wind during this event is fluctuating, but not particularly strongly—it's basically background noise. But solar wind is basically never steady; it's constantly putting some energy into the magnetosphere."

This deposit of energy into Earth's magnetic system has far-reaching effects:for one, changes in the composition and density of Earth's upper atmosphere can garble communications and navigation signals, an effect often characterized by total electron content. Changes in density can also affect the orbits of satellites to great degree, introducing uncertainty about precise position.

ESPERTO DI

Earth isn't the only planet where the solar wind has measurable effects—and studying other worlds in our solar system can help scientists understand some of the solar wind's effects on Earth and how it influenced the evolution of Earth and other worlds throughout the solar system's history.

At Mars, the solar wind coupled with Mars' lack of a global magnetic field may be a major factor in the dry, barren world the Red Planet is today. Though Mars was once much like Earth—warm, with liquid water and a thick atmosphere—the planet has changed drastically over the course of its four-billion-year history, with most of its atmosphere being stripped away to space. With similar processes observed here on Earth, scientists leverage understanding of solar-planetary interactions at Mars to determine how processes leading to atmospheric escape has the ability to change whether a planet is habitable or not. Oggi, the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission, or MAVEN, studies these processes at Mars. MAVEN observations at Mars are available for this latest WHPI campaign.

Over the coming months, heliophysicists around the world will begin to study data from these observatories in depth, hoping to draw connections that reveal new knowledge about the sun and its changes that influence Earth and space across the solar system.

Parker Solar Probe is part of the NASA Heliophysics Living with a Star program to explore aspects of the sun-Earth system that directly affect life and society. The Living with a Star program is managed by the agency's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, designed, built and operates the spacecraft and manages the mission for NASA.