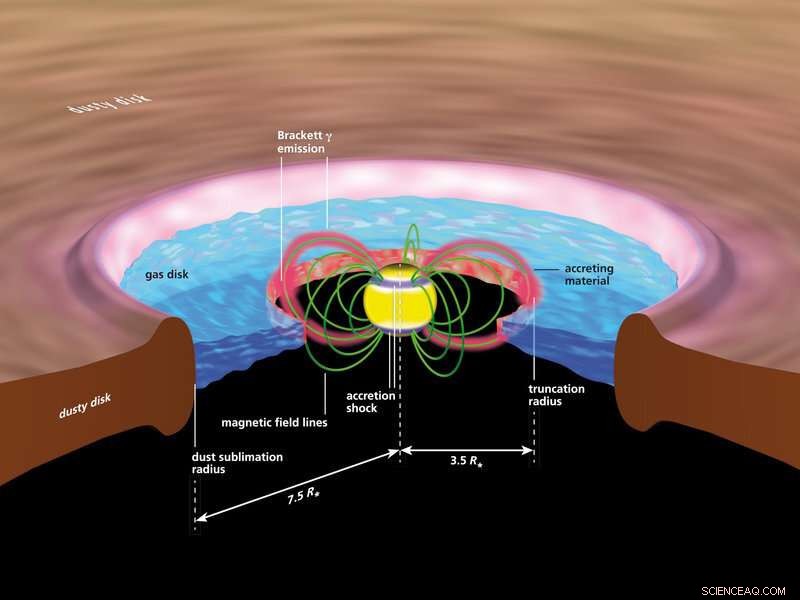

Impressione artistica dei flussi di gas caldi che aiutano le giovani stelle a crescere. I campi magnetici guidano la materia dal disco circumstellare circostante, il luogo di nascita dei pianeti, alla superficie della stella, dove producono intense raffiche di radiazioni. Credito:A. Mark Garlick

Gli astronomi hanno utilizzato lo strumento GRAVITY per studiare le immediate vicinanze di una giovane stella in modo più dettagliato che mai. Le loro osservazioni confermano una teoria vecchia di trent'anni sulla crescita delle giovani stelle:il campo magnetico prodotto dalla stella stessa dirige il materiale da un circostante disco di accrescimento di gas e polvere sulla sua superficie. I risultati, pubblicato oggi sulla rivista Natura , aiutare gli astronomi a capire meglio come si formano le stelle come il nostro Sole e come i pianeti simili alla Terra vengono prodotti dai dischi che circondano questi bambini stellari.

Quando si formano le stelle, iniziano relativamente piccoli e si trovano in profondità all'interno di una nuvola di gas. Nel corso delle successive centinaia di migliaia di anni, attirano sempre più su di sé il gas circostante, aumentando la loro massa nel processo. Utilizzando lo strumento GRAVITY, un gruppo di ricercatori che comprende astronomi e ingegneri del Max Planck Institute for Astronomy (MPIA), ha ora trovato la prova più diretta di come quel gas viene incanalato sulle giovani stelle:è guidato dal campo magnetico della stella sulla superficie in una stretta colonna.

Le scale di lunghezza rilevanti sono così piccole che anche con i migliori telescopi attualmente disponibili non sono possibili immagini dettagliate del processo. Ancora, utilizzando la più recente tecnologia di osservazione, gli astronomi possono almeno raccogliere alcune informazioni. Per il nuovo studio, i ricercatori si sono avvalsi dell'eccezionale potere risolutivo dello strumento denominato GRAVITY. Combina quattro telescopi VLT da 8 metri dell'Osservatorio europeo meridionale (ESO) presso l'osservatorio del Paranal in Cile in un telescopio virtuale in grado di distinguere piccoli dettagli, così come un telescopio con uno specchio di 100 metri.

Usando la GRAVITÀ, i ricercatori hanno potuto osservare la parte interna del disco di gas che circonda la stella TW Hydrae. "Questa stella è speciale perché è molto vicina alla Terra a soli 196 anni luce di distanza, e il disco di materia che circonda la stella è proprio di fronte a noi, " dice Rebeca García López (Istituto Max Planck per l'Astronomia, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies e University College Dublin), autore principale e principale scienziato di questo studio. "Questo lo rende un candidato ideale per sondare come la materia di un pianeta che forma il disco viene incanalata sulla superficie stellare".

L'osservazione ha permesso agli astronomi di dimostrare che la radiazione nel vicino infrarosso emessa dall'intero sistema ha effettivamente origine nella regione più interna, dove il gas idrogeno sta cadendo sulla superficie della stella. I risultati puntano chiaramente verso un processo noto come accrescimento magnetosferico, questo è, materia in caduta guidata dal campo magnetico della stella.

Nascita stellare e crescita stellare

Una stella nasce quando una regione densa all'interno di una nube di gas molecolare collassa sotto la sua stessa gravità, diventa notevolmente più denso, si riscalda durante il processo, finché alla fine la densità e la temperatura nella protostella risultante sono così alte che inizia la fusione nucleare dell'idrogeno in elio. Per protostelle fino a circa due volte la massa del Sole, i dieci milioni di anni circa immediatamente prima dell'accensione della fusione nucleare protone-protone costituiscono la cosiddetta fase T Tauri (dal nome della prima stella osservata di questo tipo, T Tauri nella costellazione del Toro).

Stelle che vediamo in quella fase del loro sviluppo, noto come stelle T Tauri, brillano abbastanza intensamente, in particolare alla luce infrarossa. Questi cosiddetti "giovani oggetti stellari" (YSO) non hanno ancora raggiunto la loro massa finale:sono circondati dai resti della nuvola da cui sono nati, in particolare dal gas che si è contratto in un disco circumstellare che circonda la stella. Nelle regioni esterne di quel disco, polvere e gas si aggregano e formano corpi sempre più grandi, che alla fine diventeranno pianeti. Grandi quantità di gas e polvere dalla regione del disco interno, d'altra parte, sono attratti dalla stella, aumentandone la massa. Ultimo, ma non per importanza, l'intensa radiazione della stella espelle una parte considerevole del gas sotto forma di vento stellare.

Linee guida per la superficie:il campo magnetico della stella

ingenuamente, si potrebbe pensare che trasportare gas o polvere su un massiccio, il corpo gravitante è facile. Anziché, si scopre che non è affatto semplice. A causa di ciò che i fisici chiamano conservazione del momento angolare, è molto più naturale per qualsiasi oggetto, sia esso pianeta o nuvola di gas, orbitare attorno a una massa piuttosto che cadere direttamente sulla sua superficie. Uno dei motivi per cui una certa materia riesce comunque a raggiungere la superficie è un cosiddetto disco di accrescimento, in cui il gas orbita attorno alla massa centrale. All'interno c'è un sacco di attrito interno che consente continuamente a parte del gas di trasferire il suo momento angolare ad altre porzioni di gas e di spostarsi ulteriormente verso l'interno. Ancora, ad una distanza dalla stella inferiore a 10 volte il raggio stellare, the accretion process gets more complex. Traversing that last distance is tricky.

Trenta anni fa, Max Camenzind, at the Landessternwarte Königstuhl (which has since become a part of the University of Heidelberg), proposed a solution to this problem. Stars typically have magnetic fields—those of our Sun, ad esempio, regularly accelerate electrically charged particles in our direction, leading to the phenomenon of Northern or Southern lights. In what has become known as magnetospheric accretion, the magnetic fields of the young stellar object guide gas from the inner rim of the circumstellar disk to the surface in distinct column-like flows, helping them to shed angular momentum in a way that allows the gas to flow onto the star.

In the simplest scenario, the magnetic field looks similar to that of the Earth. Gas from the inner rim of the disk would be funneled to the magnetic North and to the magnetic South pole of the star.

Checking up on magnetospheric accretion

Having a model that explains certain physical processes is one thing. Però, it is important to be able to test that model using observations. But the length scales in question are of the order of stellar radii, very small on astronomical scales. Fino a poco tempo fa, such length scales were too small, even around the nearest young stars, for astronomers to be able to take a picture showing all relevant details.

Schematic representation of the process of magnetospheric accretion of material onto a young star. Magnetic fields produced by the young star carry gas through flow channels from the disk to the polar regions of the star. The ionized hydrogen gas emits intense infrared radiation. When the gas hits the star's surface, shocks occur that give rise to the star's high brightness. Credit:MPIA graphics department

First indication that magnetospheric accretion is indeed present came from examining the spectra of some T Tauri stars. Spectra of gas clouds contain information about the motion of the gas. For some T Tauri stars, spectra revealed disk material falling onto the stellar surface with velocities as high as several hundred kilometers per second, providing indirect evidence for the presence of accretion flows along magnetic field lines. In alcuni casi, the strength of the magnetic field close to a T Tauri star could be directly measured by a combining high-resolution spectra and polarimetry, which records the orientation of the electromagnetic waves we receive from an object.

Più recentemente, instruments have become sufficiently advanced—more specifically:have reached sufficiently high resolution, a sufficiently good capability to discern small details—so as to allow direct observations that provide insights into magnetospheric accretion.

The instrument GRAVITY plays a key role here. It was developed by a consortium that includes the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, led by the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics. In operation since 2016, GRAVITY links the four 8-meter-telescopes of the VLT, located at the Paranal observatory of the European Southern Observatory (ESO). The instrument uses a special technique known as interferometry. The result is that GRAVITY can distinguish details so small as if the observations were made by a single telescope with a 100-m mirror.

Catching magnetic funnels in the act

In the Summer of 2019, a team of astronomers led by Jerome Bouvier of the University of Grenobles Alpes used GRAVITY to probe the inner regions of the T Tauri Star with the designation DoAr 44. It denotes the 44th T Tauri star in a nearby star forming region in the constellation Ophiuchus, catalogued in the late 1950s by the Georgian astronomer Madona Dolidze and the Armenian astronomer Marat Arakelyan. The system in question emits considerable light at a wavelength that is characteristic for highly excited hydrogen. Energetic ultraviolet radiation from the star ionizes individual hydrogen atoms in the accretion disk orbiting the star.

The magnetic field then influences the electrically charged hydrogen nuclei (each a single proton). The details of the physical processes that heat the hydrogen gas as it moves along the accretion current towards the star are not yet understood. The observed greatly broadened spectral lines show that heating occurs.

For the GRAVITY observations, the angular resolution was sufficiently high to show that the light was not produced in the circumstellar disk, but closer to the star's surface. Inoltre, the source of that particular light was shifted slightly relative to the centre of the star itself. Both properties are consistent with the light being emitted near one end of a magnetic funnel, where the infalling hydrogen gas collides with the surface of the star. Those results have been published in an article in the journal Astronomia e astrofisica .

The new results, which have now been published in the journal Natura , go one step further. In questo caso, the GRAVITY observations targeted the T Tauri star TW Hydrae, a young star in the constellation Hydra. They are based on GRAVITY observations of the T Tauri star TW Hydrae, a young star in the constellation Hydra. It is probably the best-studied system of its kind.

Too small to be part of the disk

Con quelle osservazioni, Rebeca García López and her colleagues have pushed the boundaries even further inwards. GRAVITY could see the emissions corresponding to the line associated with highly excited hydrogen (Brackett-γ, Brγ) and demonstrate that they stem from a region no more than 3.5 times the radius of the star across (about 3 million km, or 8 times the distance the distance between the Earth and the Moon).

This is a significant difference. According to all physics-based models, the inner rim of a circumstellar disk cannot possibly be that close to the star. If the light originates from that region, it cannot be emitted from any section of the disk. A quella distanza, the light also cannot be due to a stellar wind blown away by the young stellar object—the only other realistic possibility. Presi insieme, what is left as a plausible explanation is the magnetospheric accretion model.

Qual è il prossimo?

In future observations, again using GRAVITY, the researchers will try to get data that allows them a more detailed reconstruction of physical processes close to the star. "By observing the location of the funnel's lower endpoint over time, we hope to pick up clues as to how distant the magnetic North and South poles are from the star's axis of rotation, " explains Wolfgang Brandner, co-author and scientist at MPIA. If North and South Pole directly aligned with the rotation axis, their position over time would not change at all.

They also hope to pick up clues as to whether the star's magnetic field is really as simple as a North Pole–South Pole configuration. "Magnetic fields can be much more complicated and have additional poles, " explains Thomas Henning, Director at MPIA. "The fields can also change over time, which is part of a presumed explanation for the brightness variations of T Tauri stars."

Tutto sommato, this is an example of how observational techniques can drive progress in astronomy. In questo caso, the new observational techniques embody in GRAVITY were able to confirm ideas about the growth of young stellar objects that were proposed as long as 30 years ago. And future observations are set to help us understand even better how baby stars are being fed.