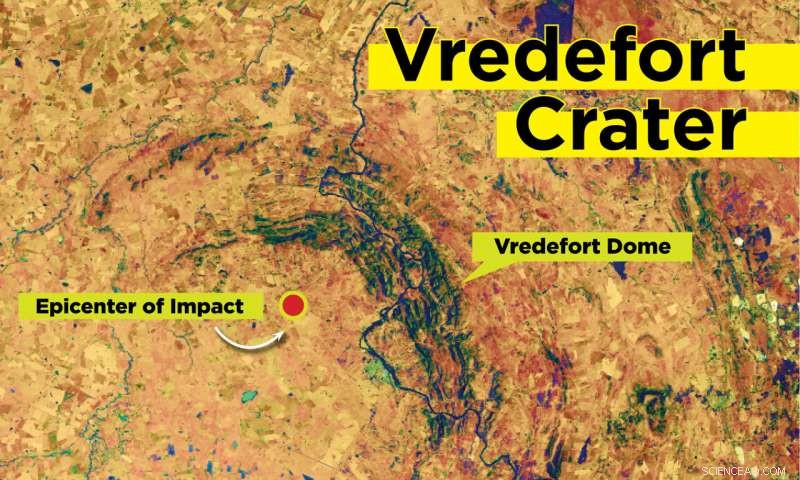

Un dispositivo d'urto, molto probabilmente un asteroide, si precipitò verso la Terra circa due miliardi di anni fa, schiantandosi contro il pianeta vicino all'odierna Johannesburg, in Sud Africa. L'impattore ha formato il cratere Vredefort, quello che oggi è il più grande cratere del nostro pianeta. Utilizzando dati di simulazione aggiornati, i ricercatori dell'Università di Rochester hanno scoperto che l'impattore che ha formato il cratere Vredefort era molto più grande di quanto si credesse in precedenza. Credito:immagine dell'Osservatorio della Terra della NASA di Lauren Dauphin / illustrazione dell'Università di Rochester di Julia Joshpe

Circa 2 miliardi di anni fa, un dispositivo d'urto si precipitò verso la Terra, schiantandosi contro il pianeta in un'area vicino all'odierna Johannesburg, in Sud Africa. L'impattore, molto probabilmente un asteroide, ha formato quello che oggi è il più grande cratere del nostro pianeta. Gli scienziati hanno ampiamente accettato, sulla base di ricerche precedenti, che la struttura dell'impatto, nota come il cratere Vredefort, fosse formata da un oggetto di circa 15 chilometri (circa 9,3 miglia) di diametro che viaggiava a una velocità di 15 chilometri al secondo.

Ma secondo una nuova ricerca dell'Università di Rochester, l'impattore potrebbe essere stato molto più grande e avrebbe avuto conseguenze devastanti in tutto il pianeta. Questa ricerca, pubblicata nel Journal of Geophysical Research:Planets , fornisce una comprensione più accurata del grande impatto e consentirà ai ricercatori di simulare meglio gli eventi di impatto sulla Terra e su altri pianeti, sia in passato che in futuro.

"Capire la più grande struttura di impatto che abbiamo sulla Terra è fondamentale", afferma Natalie Allen, ora Ph.D. studente alla John Hopkins University. Allen è la prima autrice dell'articolo, basato sulla ricerca che ha condotto durante la laurea a Rochester con Miki Nakajima, un assistente professore di scienze della Terra e dell'ambiente. "Avere accesso alle informazioni fornite da una struttura come il cratere Vredefort è una grande opportunità per testare il nostro modello e la nostra comprensione delle prove geologiche in modo da poter comprendere meglio gli impatti sulla Terra e oltre."

Le simulazioni aggiornate suggeriscono conseguenze "devastanti"

Nel corso di 2 miliardi di anni, il cratere Vredefort si è eroso. Ciò rende difficile per gli scienziati stimare direttamente le dimensioni del cratere al momento dell'impatto originale, e quindi le dimensioni e la velocità del dispositivo d'urto che ha formato il cratere.

Un oggetto di 15 chilometri di dimensione e che viaggia a una velocità di 15 chilometri al secondo produrrebbe un cratere di circa 172 chilometri di diametro. Tuttavia, questo è molto più piccolo delle attuali stime per il cratere Vredefort. Queste stime attuali si basano su nuove prove geologiche e misurazioni che stimano che il diametro originale della struttura sarebbe stato compreso tra 250 e 280 chilometri (circa 155 e 174 miglia) durante il periodo dell'impatto.

Allen, Nakajima e i loro colleghi hanno condotto simulazioni per abbinare le dimensioni aggiornate del cratere. Their results showed that an impactor would have to be much larger—about 20 to 25 kilometers—and traveling at a velocity of 15 to 20 kilometers per second to explain a crater 250 kilometers in size.

This means the impactor that formed the Vredefort crater would have been larger than the asteroid that killed off the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, forming the Chicxulub crater. That impact had damaging effects globally, including greenhouse heating, widespread forest fires, acid rain, and destruction of the ozone layer, in addition to causing the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event that killed the dinosaurs.

If the Vredefort crater was even larger and the impact more energetic than that which formed the Chicxulub crater, the Vredefort impact may have caused even more catastrophic global consequences.

"Unlike the Chicxulub impact, the Vredefort impact did not leave a record of mass extinction or forest fires, given that there were only single-cell lifeforms and no trees existed 2 billion years ago," Nakajima says. "However, the impact would have affected the global climate potentially more extensively than the Chicxulub impact did."

Dust and aerosols from the Vredefort impact would have spread across the planet and blocked sunlight, cooling the Earth's surface, she says. "This could have had a devastating effect on photosynthetic organisms. After the dust and aerosols settled—which could have taken anywhere from hours to a decade—greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide that were emitted from the impact would have raised the global temperature potentially by several degrees for a long period of time."

A multi-faceted model of Vredefort crater

The simulations also allowed the researchers to study the material ejected by the impact and the distance the material traveled from the crater. They can use this information to determine the geographic locations of land masses billions of years ago. For instance, previous research determined material from the impactor was ejected to present-day Karelia, Russia. Using their model, Allen, Nakajima, and their colleagues found that 2 billion years ago, the distance of the land mass containing Karelia would have been only 2,000 to 2,500 kilometers from the crater in South Africa—much closer than the two areas are today.

"It is incredibly difficult to constrain the location of landmasses long ago," Allen says. "The current best simulations have mapped back about a billion years, and uncertainties grow larger the further back you go. Clarifying evidence such as this ejecta layer mapping may allow researchers to test their models and help complete the view into the past."

Undergraduate research leads to publication

The idea for this paper arose as part of a final for the course Planetary Interiors (now named Physics of Planetary Interiors), taught by Nakajima, which Allen took as a junior.

Allen says the experience of having undergraduate work result in a peer-reviewed journal article was very rewarding and helped her when applying for graduate school.

"When Professor Nakajima approached me and asked if I wanted to work together to turn it into a publishable work, it was really gratifying and validating," Allen says. "I had formulated my own research idea, and it was seen as compelling enough to another scientist that they thought it was worth publishing."

She adds, "This project was way outside of my usual research comfort zone, but I thought it would be a great learning experience and would force me to apply my skills in a new way. It gave me a lot of confidence in my research abilities as I prepared to go to graduate school." + Esplora ulteriormente