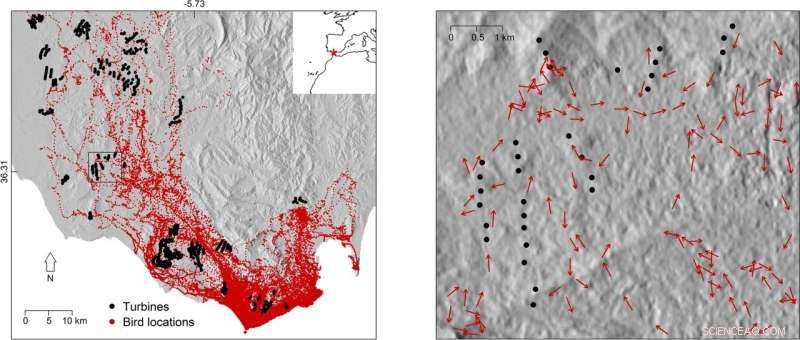

Il pannello di sinistra mostra la distribuzione spaziale delle posizioni degli uccelli e delle turbine nell'area di studio tra Cadice e Tarifa (Spagna meridionale). L'asterisco rosso nel riquadro in alto a destra indica la posizione dell'area di studio. Il pannello di destra mostra le direzioni di volo degli uccelli rispetto alle posizioni delle turbine in una piccola sezione dell'area di studio (quadrato nel pannello di sinistra). L'ombreggiatura della collina è stata aggiunta come sfondo per illustrare l'interazione tra l'uso dello spazio degli uccelli e la topografia. I dati utilizzati per illustrare l'ombreggiatura delle colline sono stati recuperati da un modello digitale di elevazione pubblicamente disponibile (https://lpdaac.usgs.gov). Credito:Rapporti scientifici (2022). DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-10295-9

Nella corsa per evitare il cambiamento climatico incontrollato, due tecnologie di energia rinnovabile vengono spinte come soluzione per alimentare le società umane:eolica e solare. Ma da molti anni le turbine eoliche sono in rotta di collisione con la conservazione della fauna selvatica. Uccelli e altri animali volanti rischiano la morte per impatto con le pale del rotore delle turbine, sollevando interrogativi sulla fattibilità del vento come pietra angolare di una politica globale per l'energia pulita. Ora, un paio di studi di localizzazione degli animali del Max Planck Institute of Animal Behaviour e dell'Università dell'East Anglia, nel Regno Unito, hanno fornito dati GPS dettagliati sul comportamento di volo degli uccelli suscettibili di collisione con le infrastrutture energetiche. Il primo, uno studio su larga scala su 1.454 uccelli di 27 specie, ha identificato i punti critici in Europa in cui gli uccelli sono particolarmente a rischio a causa delle turbine eoliche e delle linee elettriche. Il secondo ha ingrandito il comportamento degli uccelli quando volano vicino alle turbine, rivelando che gli individui eviteranno attivamente le turbine se si trovano entro un chilometro. Tracciando il movimento degli uccelli con dispositivi GPS ad alta precisione, entrambi gli studi forniscono i dati biologici dettagliati necessari per espandere l'infrastruttura delle energie rinnovabili con un impatto minimo sulla fauna selvatica.

La produzione di energia eolica è aumentata negli ultimi due decenni con l'impegno globale di passare all'energia rinnovabile dai combustibili fossili che emettono carbonio. Si prevede che la capacità di energia eolica onshore europea aumenterà di quasi quattro volte entro il 2050 e anche i paesi del Medio Oriente e del Nord Africa, come Marocco e Tunisia, hanno obiettivi per aumentare la quota di fornitura di elettricità dall'eolico onshore.

"We know from previous research that there are many more suitable locations to build wind turbines than we need in order to meet our clean energy targets up to 2050," said lead author Jethro Gauld, a Ph.D. researcher in the School of Environmental Sciences at University of East Anglia. "If we can do a better job of assessing risks to biodiversity, such as collision risk for birds, into the planning process at an early stage we can help limit the impact of these developments on wildlife while still achieving our climate targets."

Pinpointing collision hotspots in Europe

An international team of 51 researchers from 15 countries, including the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Germany, collaborated to identify the areas where these birds would be more sensitive to onshore wind turbine or power line development. The study, published in Journal of Applied Ecology , used GPS location data from 65 bird tracking studies to understand where they fly more frequently at danger height—defined as 10 to 60 meters above ground for power lines and 15 to 135 meters for wind turbines. "GPS tracking provides very accurate data on location and flight height, which cannot be obtained from direct observation, particularly from large distances," says Martin Wikelski, director at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and co-author on the study. "This study represents the first time GPS data from so many species has been pooled to create a comprehensive picture of where birds are at risk.

The resulting vulnerability maps reveal that the collision hotspots are particularly concentrated within important migration routes, along coastlines and near breeding locations. These include the Western Mediterranean coast of France, Southern Spain and the Moroccan Coast—such as around the Strait of Gibraltar—Eastern Romania, the Sinai Peninsula and the Baltic coast of Germany. The GPS data collected related to 1,454 birds from 27 species, mostly large soaring ones such as white storks. Exposure to risk varied across the species, with the Eurasian spoonbill, European eagle owl, whooper swan, Iberian imperial eagle and white stork among those flying consistently at heights where they risk collision. The authors say development of new wind turbines and transmission power lines should be minimized in these high sensitivity areas, and any developments which do occur will likely need to be accompanied by measures to reduce the risk to birds.

How birds behave near turbines

As well as providing location and flight height, GPS loggers open up an additional frontier in efforts to better plan energy infrastructure. "With GPS tracking we are able to understand exactly how birds behave as they fly close to the turbines," says Carlos Santos, an Affiliated Scientist of the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and an Assistant Professor at the Federal University of Pará, in Brazil. "Knowing how close they fly, and whether or not wind or other factors influence their flight behavior, is very important to mitigate collision rates as it can help better planning of wind farms."

A team of scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior and the University of East Anglia focused their attention on the black kite, a very common soaring bird that migrates through the Strait of Gibraltar, the narrow straight between southern Spain and North Africa. "The Strait of Gibraltar is the main migratory bottleneck for birds in western Europe but it's also a hotspot for wind farms," says Santos. "We wanted to see how soaring birds behave in this area, which represent a serious threat during their migration to Africa."

This study, published in Scientific Reports , looked at GPS information from 126 black kites as the birds approached wind turbines. The data showed that birds avoided flight paths straight to turbines as they flew closer to them. The birds started to deviate from turbines one kilometer away, but this effect was even more pronounced within 750 meters and when the wind was blowing towards the turbines. "This means that they recognize the risk of the turbines and keep a safe distance from them," says Santos.

The authors say collecting GPS data from the interaction between birds and turbines is extremely difficult. Says Santos:"You need to tag many animals to increase the chances of recording their behavior near the turbines. This is why our dataset is so uncommon. Fortunately, GPS tracking studies are becoming more common and hopefully in the near future we will be able to gather data of this sort for other soaring bird species." The authors stress that understanding how the birds perceive wind turbines and which factors attenuate or exacerbate their perception is critical to learn where to place turbines and to develop effective deterrents.