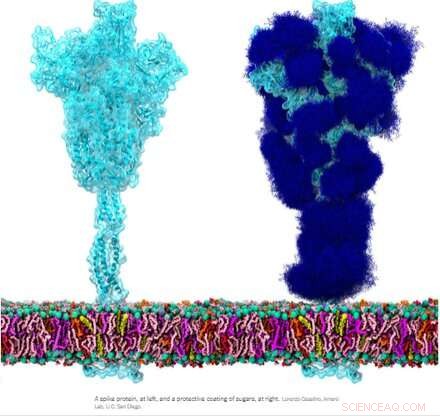

Credito:Wikipedia

La glicoproteina spike omotrimerica (S) di SARS-CoV-2, in particolare la sua subunità S2, è una proteina di fusione straordinaria. Può fondere le particelle virali alle cellule e anche fondere le cellule alle cellule per creare sincizi multiformi tra diversi fenotipi cellulari. A seconda delle versioni esatte in esame, il picco può eseguire queste prodezze tramite molteplici meccanismi che agiscono sia sul lato intracellulare che extracellulare delle membrane cellulari.

Queste funzioni di fusione sono in qualche modo analoghe alle tipiche proteine omotrimeriche ENV (inviluppo) come la nostra proteina ENV retrovirale endogena sincitina-1 e la glicoproteina ENV GP160 del virus HIV. GP160, la proteina "spike" dell'HIV, viene infine elaborata nel proprio sito di scissione della furina (che si trova anche nella sincitina-1) in una proteina GP120 e una GP41, che possono entrambe adottare distinte configurazioni pre e post-fusione. Il genoma SARS-CoV-2, tuttavia, specifica già una piccola proteina ENV separata (opportunamente designata come E), che si assembla in un presunto canale cationico con un poro di fusione centrale.

Non ci sono env, pol, gag o pro geni definiti come tali per il genoma SARS-CoV-2, come nel caso dei retrovirus, che devono integrarsi nel nostro DNA come parte del loro ciclo di vita. Curiosamente, i ricercatori hanno scoperto che la proteina spike SARS-CoV-2, comportandosi di propria iniziativa, partecipa direttamente all'attivazione dei retrovirus endogeni nelle nostre cellule che contribuisce alla patologia osservata. Cosa sta succedendo esattamente qui?

Alla luce di alcune di queste somiglianze, è stato suggerito che gli anticorpi generati contro la proteina spike potrebbero potenzialmente reagire in modo incrociato in tutti i tessuti che potrebbero esprimere proteine retrovirali endogene. In particolare, durante la gravidanza, dopo di che i trofoblasti placentari esprimono proteine ENV molto utili da molti di questi HERV tra cui ERVW1 (syncytin-1), ERVFRD-1 (syncytin-2), ERVV-1, ERVV-2, ERVH48-1, ERVMER34-1 , ERV3-1 e ERVK13-1. L'espressione della sincitina-2 nei citotrofoblasti dei villi, tuttavia, è altamente correlata al grado di gravità di alcune patologie placentari come la preeclampsia.

Fortunatamente, i ricercatori hanno scoperto che praticamente non esiste un'omologia di sequenza diretta tra spike e sincitina-1 e poche possibilità di reattività crociata. Scrivo sulla rivista Animal Cells and Systems , i ricercatori coreani hanno testato un ampio pannello di anticorpi monoclonali e sono stati in grado di concludere che mentre antiche reliquie genomiche come gli HERV possono essere attivate in vari tessuti da SARS-CoV-2, non vi è alcun rischio di reattività crociata o addirittura di infertilità.

Ma se la proteina spike è ancora molto in grado di causare una fusione cellulare indesiderata, come possiamo definire meglio questa attività apparentemente casuale e, inoltre, cosa potremmo fare al riguardo? Forse il primo passo è diventare un po' più sofisticati con la terminologia della fusione cellulare. Scrivendo sulla rivista Oncotarget , l'autore Yuri Lazebnik offre alcuni spunti di riflessione. Un sincizio prodotto da cellule dello stesso tipo, ad esempio, come nella fusione di due o più pneumociti, è chiamato omocarion. Un eterocarione, quindi, sarebbe un sincizio costituito, ad esempio, da un pneumocita fuso con un progenitore epiteliale, o forse un leucocita. In generale, una volta che le cellule si combinano, tutte le scommesse sono disattivate:non è ancora completamente noto se possano successivamente ordinare se stesse e i loro nuclei per generare prole mononucleare competente per la replicazione.

Formation of spike-induced syncytia in the lungs of COVID-10 patients has been found in many forms, each with their own emergent properties that can contribute to disease sequelae. For example, ciliated cells in the airway, alveolar type 2 pneumocytes, and epithelial progenitors have all been found to participate in the oft-observed multinucleated 'giant cells.' Throw in a spike-laden leukocyte or two and things rapidly get hard to predict. Perhaps an even more alarming situation would be formation of a syncytium in the cells lining our blood vessels that could contribute to thrombosis. The ensuing death and eventual sloughing off of a patch of inappropriately fused cells could expose a sizeable region of thrombogenic basement membrane. A 20-micron fiber of collagen, the main component of the basement membrane, is sufficient to trigger platelet-dependent clotting.

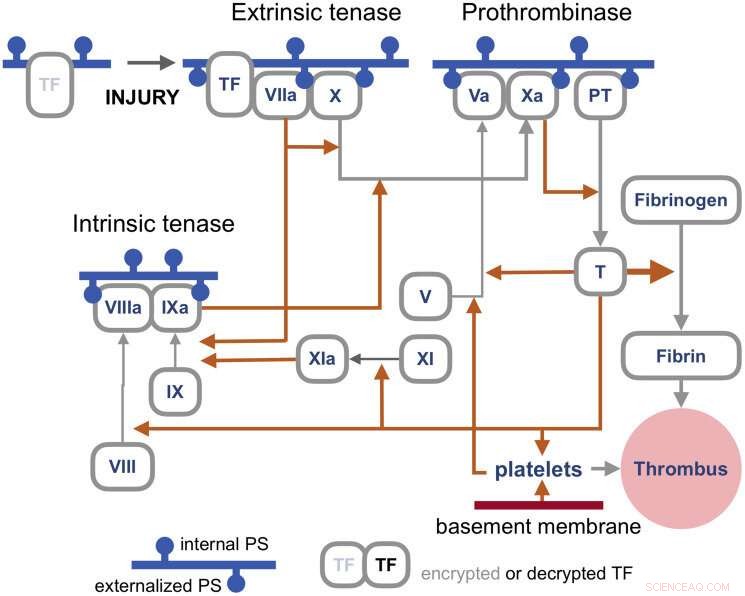

But enough of this fear-mongering. Researchers have identified a set of already approved drugs that prevent spike-induced cell fusion and inhibit TMEM16F, a critical protein for syncytium formation. TMEM16F has the dual role of being a calcium-activated ion channel that regulates chloride secretion, as well as a lipid scramblase that relocates phosphatidylserine (PS) to the cell surface. This PS externalization is required for cell fusion in many systems, including spike-induced syncytia. Incidentally, scramblases also control the rate-limiting steps of the blood coagulation cascade, and may be the mechanism behind spike-induced thrombosis.

The blood coagulation pathways are a whole separate complex can of worms, but suffice it to say here that the primary trigger of coagulation induced by viral infections is the so-called extrinsic 'tenase.' Tenases are enzymes that process Factor X, or FX, (hence ten-ase), in the Tissue Factor (TF) activation pathway, which essentially act as the fuse for thrombus generation. The resulting complexes are assembled on externalized PS in the presence of calcium ions. TF is, in a sense, encrypted and so is unable to activate its downstream target factor FVIIa until it is de-encrypted by externalized PS.

Coagulation pathways. Credit:Y. Lazebnik 2021

The realization that some fusogenic viral, or even retroviral proteins, which are fortuitously expressed in particular regions of the body may likely contribute to thrombotic events is of tremendous practical importance. One need look no further than Moderna's ample proposed pipeline for therapeutic mRNA-delivered amenities based on these proteins for all manner of viral insults to have some pause for inspection. There is certainly no shortage of methods currently employed for building antigenic spike proteins for vaccinations. Depending of how much of the spike code is used, which cleavage sequences are included, and which parts are stabilized, very different proteins can be made. It is probably fair to say that full-length spikes in large questionable vectors or inactivated viral particles have been largely de-emphasized in favor of smaller but more immunogenic concoctions.

Lungs and blood vessels are certainly critical areas of concern in any SARS-CoV-2 infection, but what our precious neurons—can spike fuse them as well? Clearly it can fuse neurons in brain organoids, but then again, what can't researchers do with these instant research publication miracles. In looking more braodly at other kinds of viruses, the fusion of neurons, glial cells, and even axons seems to be par for the course in causing a myriad constellation of potential neurological issues. For example, the pseudorabies virus bridges synapses to electrically couple the activity of neurons by fusing their axons. Fusions with glia have similarly been detected and linked with lasting neuropathic pain after the acute phase of herpes zoster (shingles). As of this Wednesday, we all are further aware that SARS-CoV-2 can utilize the protein vimentin as a way to infect endothelial cells. It should escape no one's notice, or at least that of the neuroscientists, that vimentin is the prime marker used for identifying glial cells.

Additionally, the rapidly expanding body of work looking at endogenous retrovirus re-activation in neurodegenerative disease further suggests to the rational mind that cell fusion may also be involved in this kind of pathology.