Gli antichi alchimisti hanno cercato di trasformare il piombo e altri metalli comuni in oro e platino. I chimici moderni nel laboratorio di Paul Chirik a Princeton stanno trasformando le reazioni che dipendono da metalli preziosi non rispettosi dell'ambiente, trovare alternative più economiche e più ecologiche per sostituire il platino, rodio e altri metalli preziosi nella produzione di farmaci e altre reazioni.

Hanno trovato un approccio rivoluzionario che utilizza cobalto e metanolo per produrre un farmaco per l'epilessia che in precedenza richiedeva rodio e diclorometano, un solvente tossico. La loro nuova reazione funziona più velocemente e in modo più economico, e probabilmente ha un impatto ambientale molto minore, disse Chirik, l'Edwards S. Sanford Professore di Chimica. "Ciò mette in evidenza un principio importante nella chimica verde:la soluzione più ambientale può anche essere quella preferita dal punto di vista chimico, " ha detto. La ricerca è stata pubblicata sulla rivista Scienza il 25 maggio.

"La scoperta e il processo farmaceutici coinvolgono tutti i tipi di elementi esotici, " Chirik ha detto. "Abbiamo iniziato questo programma forse 10 anni fa, ed è stato davvero motivato dal costo. Metalli come rodio e platino sono molto costosi, ma man mano che il lavoro si è evoluto, ci siamo resi conto che c'è molto di più del semplice prezzo. ... Ci sono enormi preoccupazioni ambientali, se pensi di estrarre il platino dal terreno. Tipicamente, devi andare a circa un miglio di profondità e spostare 10 tonnellate di terra. Questo ha un'enorme impronta di anidride carbonica".

Chirik e il suo team di ricerca hanno collaborato con i chimici di Merck &Co., Inc., per trovare modi più rispettosi dell'ambiente per creare i materiali necessari per la moderna chimica dei farmaci. La collaborazione è stata resa possibile dal programma della National Science Foundation's Grant Opportunities for Academic Liaison with Industry (GOALI).

Un aspetto difficile è che molte molecole hanno forme destrorse e mancine che reagiscono in modo diverso, con conseguenze a volte pericolose. La Food and Drug Administration ha requisiti rigorosi per assicurarsi che i farmaci abbiano solo una "mano" alla volta, noti come farmaci a singolo enantiomero.

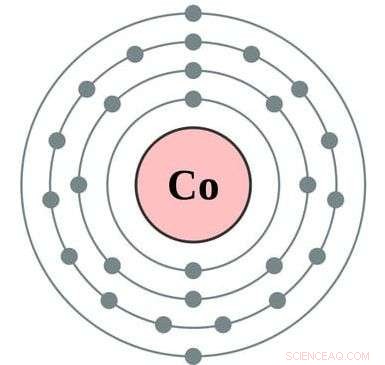

"I chimici sono chiamati a scoprire metodi per sintetizzare solo una mano di molecole di farmaco piuttosto che sintetizzarle entrambe e poi separarle, " disse Chirik. " Catalizzatori metallici, storicamente basata su metalli preziosi come il rodio, hanno il compito di risolvere questa sfida. Il nostro articolo dimostra che un metallo più abbondante sulla Terra, cobalto, può essere utilizzato per sintetizzare il farmaco per l'epilessia Keppra come una sola mano."

Cinque anni fa, i ricercatori nel laboratorio di Chirik hanno dimostrato che il cobalto potrebbe produrre molecole organiche a singolo enantiomero, ma solo usando composti relativamente semplici e non attivi dal punto di vista medicinale e usando solventi tossici.

"Siamo stati ispirati a spingere la nostra dimostrazione di principio in esempi del mondo reale e dimostrare che il cobalto potrebbe superare i metalli preziosi e funzionare in condizioni più compatibili con l'ambiente, " ha detto. Hanno scoperto che la loro nuova tecnica a base di cobalto è più veloce e più selettiva rispetto all'approccio brevettato al rodio.

"Il nostro documento dimostra un raro caso in cui un metallo di transizione abbondante sulla Terra può superare le prestazioni di un metallo prezioso nella sintesi di farmaci a singolo enantiomero, " ha detto. "Ciò a cui stiamo iniziando a passare è che i catalizzatori abbondanti sulla Terra non solo sostituiscono quelli di metalli preziosi, ma offrono vantaggi distinti, che si tratti di una nuova chimica che nessuno ha mai visto prima o di una migliore reattività o di un impatto ambientale ridotto".

Non solo i metalli di base sono più economici e molto più rispettosi dell'ambiente rispetto ai metalli rari, ma la nuova tecnica opera in metanolo, che è molto più verde dei solventi clorurati richiesti dal rodio.

"La produzione di molecole di farmaci, per la loro complessità, is one of the most wasteful processes in the chemical industry, " said Chirik. "The majority of the waste generated is from the solvent used to conduct the reaction. The patented route to the drug relies on dichloromethane, one of the least environmentally friendly organic solvents. Our work demonstrates that Earth-abundant catalysts not only operate in methanol, a green solvent, but also perform optimally in this medium.

"This is a transformative breakthrough for Earth-abundant metal catalysts, as these historically have not been as robust as precious metals. Our work demonstrates that both the metal and the solvent medium can be more environmentally compatible."

Methanol is a common solvent for one-handed chemistry using precious metals, but this is the first time it has been shown to be useful in a cobalt system, noted Max Friedfeld, the first author on the paper and a former graduate student in Chirik's lab.

Cobalt's affinity for green solvents came as a surprise, said Chirik. "For a decade, catalysts based on Earth-abundant metals like iron and cobalt required very dry and pure conditions, meaning the catalysts themselves were very fragile. By operating in methanol, not only is the environmental profile of the reaction improved, but the catalysts are much easier to use and handle. This means that cobalt should be able to compete or even outperform precious metals in many applications that extend beyond hydrogenation."

The collaboration with Merck was key to making these discoveries, hanno notato i ricercatori.

Chirik said:"This is a great example of an academic-industrial collaboration and highlights how the very fundamental—how do electrons flow differently in cobalt versus rhodium?—can inform the applied—how to make an important medicine in a more sustainable way. I think it is safe to say that we would not have discovered this breakthrough had the two groups at Merck and Princeton acted on their own."

The key was volume, said Michael Shevlin, an associate principal scientist at the Catalysis Laboratory in the Department of Process Research &Development at Merck &Co., Inc., and a co-author on the paper.

"Instead of trying just a few experiments to test a hypothesis, we can quickly set up large arrays of experiments that cover orders of magnitude more chemical space, " Shevlin said. "The synergy is tremendous; scientists like Max Friedfeld and [co-author and graduate student] Aaron Zhong can conduct hundreds of experiments in our lab, and then take the most interesting results back to Princeton to study in detail. What they learn there then informs the next round of experimentation here."

Chirik's lab focuses on "homogenous catalysis, " the term for reactions using materials that have been dissolved in industrial solvents.

"Homogenous catalysis is usually the realm of these precious metals, the ones at the bottom of the periodic table, " Chirik said. "Because of their position on the periodic table, they tend to go by very predictable electron changes—two at a time—and that's why you can make jewelry out of these elements, because they don't oxidize, they don't interact with oxygen. So when you go to the Earth-abundant elements, usually the ones on the first row of the periodic table, the electronic structure—how the electrons move in the element—changes, and so you start getting one-electron chemistry, and that's why you see things like rust for these elements.

Chirik's approach proposes a radical shift for the whole field, said Vy Dong, a chemistry professor at the University of California-Irvine who was not involved in the research. "Traditional chemistry happens through what they call two-electron oxidations, and Paul's happens through one-electron oxidation, " she said. "That doesn't sound like a big difference, but that's a dramatic difference for a chemist. That's what we care about—how things work at the level of electrons and atoms. When you're talking about a pathway that happens via half of the electrons that you'd normally expect, it's a big deal. ... That's why this work is really exciting. You can imagine, once we break free from that mold, you can start to apply it to other things, pure."

"We're working in an area of the periodic table where people haven't, per molto tempo, so there's a huge wealth of new fundamental chemistry, " said Chirik. "By learning how to control this electron flow, the world is open to us."