Stai ben indietro. Credito:RHJPhtotoandilustration

È passato un anno da quando Horizon Nuclear Power, una società di proprietà di Hitachi, ha confermato che si stava ritirando dalla costruzione della centrale nucleare Wylfa da 20 miliardi di sterline ad Anglesey, nel Galles settentrionale. Il conglomerato industriale giapponese ha citato il mancato raggiungimento di un accordo di finanziamento con il governo del Regno Unito a causa dell'aumento dei costi e il governo è ancora in trattative con altri attori per cercare di portare avanti il progetto.

Il prezzo delle azioni di Hitachi è salito del 10% quando ha annunciato il suo ritiro, riflettendo il sentimento negativo degli investitori nei confronti della costruzione di grandi centrali nucleari complesse e altamente regolamentate. Con i governi riluttanti a sovvenzionare l'energia nucleare a causa dei costi elevati, in particolare dopo il disastro di Fukushima del 2011, il mercato ha sottovalutato il potenziale di questa tecnologia per affrontare l'emergenza climatica fornendo elettricità a basse emissioni di carbonio abbondante e affidabile.

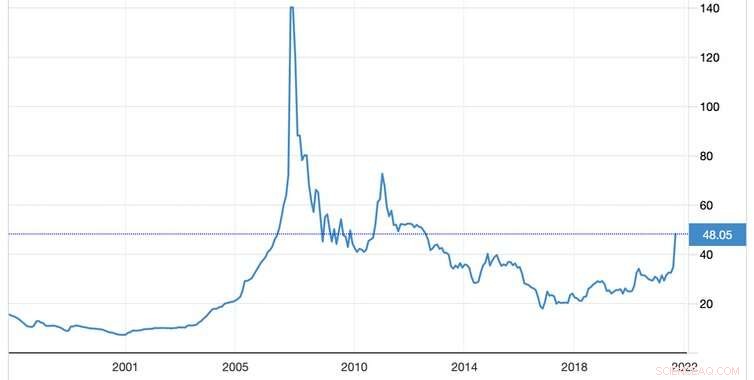

I prezzi dell'uranio hanno rispecchiato a lungo questa realtà. Il combustibile primario per le centrali nucleari è scivolato per gran parte degli anni 2010, senza segni di una grande inversione di tendenza. Eppure, da metà agosto, i prezzi sono aumentati di circa il 60% mentre investitori e speculatori si affrettano ad accaparrarsi la merce. Il prezzo è di circa 48 dollari USA per libbra (453 g), essendo stato pari a 28,99 dollari USA il 16 agosto. Quindi cosa si nasconde dietro questo rally e cosa significa per l'energia nucleare?

Prezzo dell'uranio

Il mercato dell'uranio

La domanda di uranio è limitata alla produzione di energia nucleare e alle apparecchiature mediche. La domanda globale annuale è di 150 milioni di sterline, con le centrali nucleari che cercano di assicurarsi contratti circa due anni prima dell'uso.

Sebbene la domanda di uranio non sia immune da flessioni economiche, è meno esposta rispetto ad altri metalli industriali e materie prime. La maggior parte della domanda è distribuita in circa 445 centrali nucleari operanti in 32 paesi, con l'offerta concentrata in una manciata di miniere. Il Kazakistan è facilmente il maggior produttore con oltre il 40% della produzione, seguito da Australia (13%) e Namibia (11%).

Poiché la maggior parte dell'uranio estratto viene utilizzato come combustibile dalle centrali nucleari, il suo valore intrinseco è strettamente legato sia alla domanda attuale che al potenziale futuro di questo settore. Il mercato include non solo i consumatori di uranio, ma anche gli speculatori, che acquistano quando pensano che il prezzo sia basso, potenzialmente aumentando il prezzo. Uno di questi speculatori a lungo termine è lo Sprott Physical Uranium Trust con sede a Toronto, che nelle ultime settimane ha acquistato quasi 6 milioni di sterline (o un valore di 240 milioni di dollari) di uranio.

Perché l'ottimismo degli investitori potrebbe aumentare

Sebbene sia opinione diffusa che l'energia nucleare debba svolgere un ruolo fondamentale nella transizione verso l'energia pulita, i costi elevati l'hanno resa non competitiva rispetto ad altre fonti energetiche. Ma grazie al forte aumento dei prezzi dell'energia, la competitività del nucleare sta migliorando. Stiamo anche assistendo a un maggiore impegno nei confronti di nuove centrali nucleari dalla Cina e altrove. Meanwhile, innovative nuclear technologies such as small modular reactors (SMRs), which are being developed in countries including China, the US, UK and Poland, promise to reduce upfront capital costs.

Credit:Trading Economics

Combined with recent optimistic releases about nuclear power from the World Nuclear Association and the International Atomic Energy Agency (the IAEA upped its projections for future nuclear-power use for the first time since Fukushima) this is all making investors more bullish about future uranium demand.

The effect on the price has also been multiplied by issues on the supply side. Due to the previously low prices, uranium mines around the world have been mothballed for several years. For example, Cameco, the world's largest listed uranium company, suspended production at its McArthur River mine in Canada in 2018.

Global supply was further hit by COVID-19, with production falling by 9.2% in 2020 as mining was disrupted. At the same time, since uranium has no direct substitute, and is involved with national security, several countries including China, India and the US have amassed large stockpiles—further limiting available supply.

Hang on tight

When you compare the cost of producing electricity over the lifetime of a power station, the cost of uranium has a much smaller impact on a nuclear plant than the equivalent effect of, say, gas or biomass:it's 5% compared to around 80% in the others. As such, a big rise in the price of uranium will not massively affect the economics of nuclear power.

Yet there is certainly a risk of turbulence in this market over the months ahead. In 2021, markets for the likes of Gamestop and NFTs have become iconic examples of speculative interest and irrational exuberance—optimism driven by mania rather than a sober evaluation of the economic fundamentals.

The uranium price surge also appears to be catching the attention of transient investors. There are indications that shares in companies and funds (like Sprott) exposed to uranium are becoming meme stocks for the r/WallStreetBets community on Reddit. Irrational exuberance may not have explained the initial surge in uranium prices, but it may mean more volatility to come.

We could therefore see a bubble in the uranium market, and don't be surprised if it is followed by an over-correction to the downside. Because of the growing view that the world will need significantly more uranium for more nuclear power, this will likely incentivise increased mining and the release of existing reserves to the market. In the same way as supply issues have exacerbated the effect of heightened demand on the price, the same thing could happen in the opposite direction when more supply becomes available.

You can think of all this as symptomatic of the current stage in the uranium production cycle:a glut of reserves has suppressed prices too low to justify extensive mining, and this is being followed by a price surge which will incentivise more mining. The current rally may therefore act as a vital step to ensuring the next phase of the nuclear power industry is adequately fuelled.

Amateur traders should be careful not to get caught on the wrong side of this shift. But for a metal with a half life of 700 million years, serious investors can perhaps afford to wait it out.