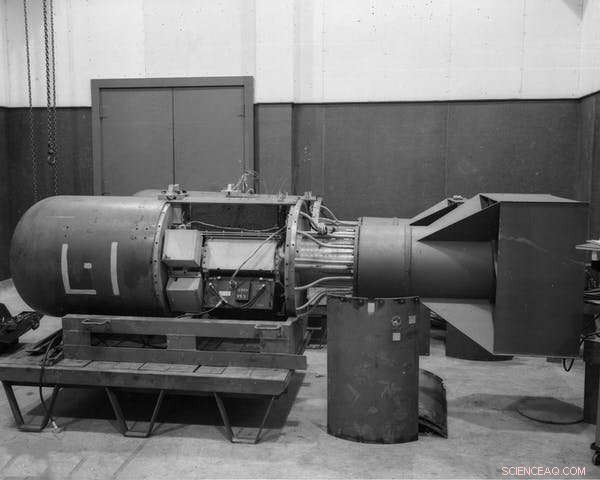

La bomba atomica, nome in codice "Little Boy", dello stesso tipo sganciata in seguito su Hiroshima, presso il Los Alamos National Laboratory nel 1944. Credit:Shutterstock

In meno di 24 ore il Bollettino degli Scienziati Atomici aggiornerà il Doomsday Clock. Attualmente sono trascorsi 100 secondi da mezzanotte, il momento metaforico in cui la razza umana potrebbe distruggere il mondo con tecnologie di sua creazione.

Le mani non sono mai state così vicine a mezzanotte. Ci sono poche speranze che ritorni in quello che sarà il suo 75° anniversario.

Unisciti a noi per l'annuncio del 75° anniversario del Doomsday Clock giovedì 20 gennaio alle 10:00 EST

Dettagli:https://t.co/UgE8wtUvND pic.twitter.com/RyWu91AnfP

— Bollettino degli scienziati atomici (@BulletinAtomic) 9 gennaio 2022

L'orologio è stato originariamente concepito come un modo per attirare l'attenzione sulla conflagrazione nucleare. Ma gli scienziati che fondarono il Bollettino nel 1945 erano meno concentrati sull'uso iniziale della "bomba" che sull'irrazionalità di accumulare armi per il bene dell'egemonia nucleare.

Si resero conto che più bombe non aumentavano le possibilità di vincere una guerra o di mettere al sicuro qualcuno quando una sola bomba sarebbe stata sufficiente per distruggere New York.

Sebbene l'annientamento nucleare rimanga la minaccia esistenziale più probabile e acuta per l'umanità, ora è solo una delle potenziali catastrofi misurate dal Doomsday Clock. Come afferma il Bollettino:"L'orologio è diventato un indicatore universalmente riconosciuto della vulnerabilità del mondo alla catastrofe causata dalle armi nucleari, dai cambiamenti climatici e dalle tecnologie dirompenti in altri settori".

Più minacce connesse

A livello personale, sento un certo senso di parentela accademica con gli orologiai. I miei mentori, in particolare Aaron Novick, e altri che hanno influenzato profondamente il modo in cui vedo la mia disciplina scientifica e il mio approccio alla scienza, sono stati tra coloro che hanno formato e si sono uniti al primo Bulletin.

Nel 2022, il loro avvertimento si estende oltre le armi di distruzione di massa per includere altre tecnologie che concentrano i rischi potenzialmente esistenziali, compresi i cambiamenti climatici e le sue cause profonde nel consumo eccessivo e nell'estrema ricchezza.

Molte di queste minacce sono già note. Ad esempio, l'uso commerciale di sostanze chimiche è pervasivo, così come i rifiuti tossici che crea. Ci sono decine di migliaia di discariche di rifiuti su larga scala solo negli Stati Uniti, con 1.700 "siti superfund" pericolosi prioritari per la bonifica.

Come ha mostrato l'uragano Harvey quando ha colpito l'area di Houston nel 2017, questi siti sono estremamente vulnerabili. An estimated two million kilograms of airborne contaminants above regulatory limits were released, 14 toxic waste sites were flooded or damaged, and dioxins were found in a major river at levels over 200 times higher than recommended maximum concentrations.

That was just one major metropolitan area. With increasing storm severity due to climate change, the risks to toxic waste sites grow.

At the same time, the Bulletin has increasingly turned its attention to the rise of artificial intelligence, autonomous weaponry, and mechanical and biological robotics.

The movie clichés of cyborgs and "killer robots" tend to disguise the true risks. For example, gene drives are an early example of biological robotics already in development. Genome editing tools are used to create gene drive systems that spread through normal pathways of reproduction but are designed to destroy other genes or offspring of a particular sex.

Climate change and affluence

As well as being an existential threat in its own right, climate change is connected to the risks posed by these other technologies.

Both genetically engineered viruses and gene drives, for example, are being developed to stop the spread of infectious diseases carried by mosquitoes, whose habitats spread on a warming planet.

Once released, however, such biological "robots" may evolve capabilities beyond our ability to control them. Even a few misadventures that reduce biodiversity could provoke social collapse and conflict.

Similarly, it's possible to imagine the effects of climate change causing concentrated chemical waste to escape confinement. Meanwhile, highly dispersed toxic chemicals can be concentrated by storms, picked up by floodwaters and distributed into rivers and estuaries.

The result could be the despoiling of agricultural land and fresh water sources, displacing populations and creating "chemical refugees."

Resetting the clock

Given that the Doomsday Clock has been ticking for 75 years, with myriad other environmental warnings from scientists in that time, what of humanity's ability to imagine and strive for a different future?

Part of the problem lies in the role of science itself. While it helps us understand the risks of technological progress, it also drives that process in the first place. And scientists are people, too—part of the same cultural and political processes that influence everyone.

J. Robert Oppenheimer—the "father of the atomic bomb"—described this vulnerability of scientists to manipulation, and to their own naivete, ambition and greed, in 1947:"In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose."

If the bomb was how physicists came to know sin, then perhaps those other existential threats that are the product of our addiction to technology and consumption are how others come to know it, too.

Ultimately, the interrelated nature of these threats is what the Doomsday Clock exists to remind us of.