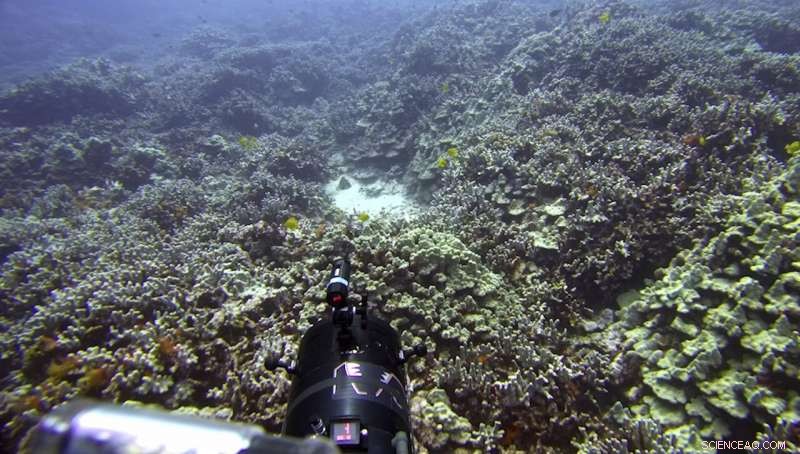

Questo 12 settembre La foto del 2019 mostra il corallo sbiancato nella baia di Kahala'u a Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. Appena quattro anni dopo che una grande ondata di caldo marino ha ucciso quasi la metà del corallo di questa costa, ricercatori federali prevedono che un altro giro di acqua calda causerà uno dei peggiori sbiancamenti dei coralli che la regione abbia mai visto. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

Ai margini di un'antica colata lavica dove rocce nere frastagliate incontrano il Pacifico, piccole case fuori dalla rete si affacciano sulle calme acque blu di Papa Bay sulla Big Island delle Hawaii, senza turisti o hotel in vista. Qui, una delle barriere coralline più abbondanti e vivaci delle isole prospera appena sotto la superficie.

Eppure, anche questo litorale remoto lontano dagli impatti della protezione solare chimica, calpestare i piedi e le acque reflue industriali sta mostrando i primi segni di quella che dovrebbe essere una stagione catastrofica per il corallo alle Hawaii.

Appena quattro anni dopo che una grande ondata di caldo marino ha ucciso quasi la metà del corallo di questa costa, ricercatori federali prevedono che un altro giro di acqua calda causerà uno dei peggiori sbiancamenti dei coralli che la regione abbia mai sperimentato.

"Nel 2015, abbiamo raggiunto temperature che non abbiamo mai registrato alle Hawaii, " ha detto Jamison Gove, un oceanografo della National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "Ciò che è veramente importante o allarmante, probabilmente in modo più appropriato, su questo evento è che abbiamo seguito il punto in cui eravamo in questo momento nel 2015".

I ricercatori che utilizzano apparecchiature ad alta tecnologia per monitorare le barriere coralline delle Hawaii stanno vedendo i primi segni di sbiancamento a Papa Bay e altrove causato da un'ondata di calore marino che ha fatto salire le temperature a livelli record per mesi. Giugno, Luglio e parti di agosto hanno tutti registrato le temperature oceaniche più calde mai registrate intorno alle isole Hawaii. Finora a settembre, le temperature oceaniche sono inferiori solo a quelle osservate nel 2015.

Questo 12 settembre La foto del 2019 mostra il pesce vicino al corallo in una baia sulla costa occidentale della Big Island vicino a Captain Cook, Hawaii. Appena quattro anni dopo che una grande ondata di caldo marino ha ucciso quasi la metà del corallo di questa costa, ricercatori federali prevedono che un altro giro di acqua calda causerà uno dei peggiori sbiancamenti dei coralli che la regione abbia mai visto. (Foto AP/Brian Skoloff)

I meteorologi prevedono che le alte temperature nel Pacifico settentrionale continueranno a pompare calore nelle acque delle Hawaii fino a ottobre.

"Le temperature sono state calde per molto tempo, " Gove ha detto. "Non è solo quanto fa caldo. È per quanto tempo quelle temperature oceaniche rimangono calde".

Le barriere coralline sono vitali in tutto il mondo in quanto non solo forniscono un habitat per i pesci, la base della catena alimentare marina, ma cibo e medicine per gli esseri umani. Creano anche una barriera costiera essenziale che rompe le grandi onde oceaniche e protegge le coste densamente popolate dalle mareggiate durante gli uragani.

Alle Hawaii, le barriere coralline sono anche una parte importante dell'economia:il turismo prospera in gran parte grazie alle barriere coralline che aiutano a creare e proteggere le iconiche spiagge di sabbia bianca, offrono snorkeling e immersioni, e aiuta a formare onde che attirano surfisti da tutto il mondo.

Questo 12 settembre La foto del 2019 mostra il corallo sbiancato nella baia di Kahala'u a Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. Appena quattro anni dopo che una grande ondata di caldo marino ha ucciso quasi la metà del corallo di questa costa, ricercatori federali prevedono che un altro giro di acqua calda causerà uno dei peggiori sbiancamenti dei coralli che la regione abbia mai visto. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

Le temperature oceaniche non sono uniformemente calde in tutto lo stato, Ha notato. Vento locale, le correnti e persino gli elementi a terra possono creare punti caldi nell'acqua.

"Ci sono cose come due vulcani giganti sulla Big Island che bloccano gli alisei predominanti, " facendo la costa occidentale dell'isola, dove siede Papa Bay, una delle parti più calde dello stato, Gove ha detto. Ha detto che si aspetta un "severo" sbiancamento dei coralli in quei luoghi.

"Questo è diffuso, Sbiancamento al 100% della maggior parte dei coralli, " Ha detto Gove. E molti di quei coralli si stanno ancora riprendendo dall'evento di sbiancamento del 2015, il che significa che sono più suscettibili allo stress termico.

Secondo NOAA, le cause dell'ondata di caldo includono un modello meteorologico persistente di bassa pressione tra le Hawaii e l'Alaska che ha indebolito i venti che altrimenti potrebbero mescolarsi e raffreddare le acque superficiali in gran parte del Pacifico settentrionale. La causa non è chiara:potrebbe riflettere il solito movimento caotico dell'atmosfera, oppure potrebbe essere correlato al riscaldamento degli oceani e ad altri effetti del cambiamento climatico causato dall'uomo.

In questo 13 settembre, Immagine del 2019 tratta da un video fornito dal Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science dell'Arizona State University, L'ecologo Greg Asner si tuffa su una barriera corallina a Papa Bay vicino a Captain Cook, Hawaii. "Quasi tutte le specie che monitoriamo hanno almeno un po' di sbiancamento, " Asner said. (Greg Asner/Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science via AP)

Beyond this event, oceanic temperatures will continue to rise in the coming years, Gove said. "There's no question that global climate change is contributing to what we're experiencing, " Egli ha detto.

For coral, hot water means stress, and prolonged stress kills these creatures and can leave reefs in shambles.

Bleaching occurs when stressed corals release algae that provide them with vital nutrients. That algae also gives the coral its color, so when it's expelled, the coral turns white.

Gove said researchers have a technological advantage for monitoring and gleaning insights into this year's bleaching, data that could help save reefs in the future.

"We're trying to track this event in real time via satellite, which is the first time that's ever been done, " Gove said.

In remote Papa Bay, most of the corals have recovered from the 2015 bleaching event, but scientists worry they won't fare as well this time.

In this Sept. 13, 2019, image taken from video provided by Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, ecologist Greg Asner prepares a camera fish trap on a coral reef in Papa Bay near Captain Cook, Hawaii. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " Asner said. (Greg Asner/Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science via AP)

"Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " said ecologist Greg Asner, director of Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, after a dive in the bay earlier this month.

Asner told The Associated Press that sensors showed the bay was about 3.5 degrees Fahrenheit above what is normal for this time of year.

He uses advanced imaging technology mounted to aircrafts, satellite data, underwater sensors and information from the public to give state and federal researchers like Gove the information they need.

"What's really important here is that we're taking these (underwater) measurements, connecting them to our aircraft data and then connecting them again to the satellite data, " Asner said. "That lets us scale up to see the big picture to get the truth about what's going on here."

In this Sept. 13, 2019 image taken from video provided by Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, ecologist Greg Asner dives over a coral reef in Papa Bay near Captain Cook, Hawaii. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " Asner said. (Greg Asner/Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science via AP)

Scientists will use the information to research, tra l'altro, why some coral species are more resilient to thermal stress. Some of the latest research suggests slowly exposing coral to heat in labs can condition them to withstand hotter water in the future.

"After the heat wave ends, we will have a good map with which to plan restoration efforts, " Asner said.

Nel frattempo, Hawaii residents like Cindi Punihaole Kennedy are pitching in by volunteering to educate tourists. Punihaole Kennedy is director of the Kahalu'u Bay Education Center, a nonprofit created to help protect Kahalu'u Bay, a popular snorkeling spot near the Big Island's tourist center of Kailua-Kona.

The bay and surrounding beach park welcome more than 400, 000 visitors a year, lei disse.

"We share with them what to do and what not to do as they enter the bay, " she said. "For instance, avoid stepping on the corals or feeding the fish."

In this Sept. 13, 2019 image taken from video provided by Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, ecologist Greg Asner dives over a coral reef in Papa Bay near Captain Cook, Hawaii. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " Asner said. (Greg Asner/Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science via AP)

In this Sept. 12, 2019 foto, fish swim near bleaching coral in Kahala'u Bay in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. Just four years after a major marine heat wave killed nearly half of this coastline's coral, federal researchers are predicting another round of hot water will cause some of the worst coral bleaching the region has ever seen. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 12, 2019 foto, sea urchins and fish are seen near bleaching coral in Kahala'u Bay in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. Just four years after a major marine heat wave killed nearly half of this coastline's coral, federal researchers are predicting another round of hot water will cause some of the worst coral bleaching the region has ever seen. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 12, 2019 foto, fish swim near bleaching coral in Kahala'u Bay in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. Coral reefs are vital around the world as they not only provide a habitat for fish—the base of the marine food chain—but food and medicine for humans. They also create an essential shoreline barrier that breaks apart large ocean swells and protects densely populated shorelines from storm surges during hurricanes. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 12, 2019 foto, visitors stand in Kahala'u Bay in Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. Hawaii residents like Cindi Punihaole Kennedy are pitching in by volunteering to educate tourists. Punihaole Kennedy is director of the Kahalu'u Bay Education Center, a nonprofit created to help protect Kahalu'u Bay, a popular snorkeling spot near the Big Island's tourist center of Kailua-Kona. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

This Sept. 13, 2019 photo shows a chunk of bleached, dead coral shown on a wall near a bay on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawaii. Coral reefs are vital around the world as they not only provide a habitat for fish—the base of the marine food chain—but food and medicine for humans. They also create an essential shoreline barrier that breaks apart large ocean swells and protects densely populated shorelines from storm surges during hurricanes. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 13, 2019 foto, researchers prepare to dive on a coral reef on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawaii. One of the state's most vibrant coral reefs thrives just below the surface in a bay on the west coast of Hawaii's Big Island. Qui, on a remote shoreline far from the impacts of sunscreen and throngs of tourists, scientists see the early signs of what's expected to be a catastrophic season of coral bleaching in Hawaii. The ocean here is about three and a half degrees above normal for this time of year. Coral can recover from bleaching, but when it is exposed to heat over several years, the likelihood of survival decreases. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 11, 2019 foto, a green sea turtle swims near coral in a bay on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawaii. Just four years after a major marine heat wave killed nearly half of this coastline's coral, federal researchers are predicting another round of hot water will cause some of the worst coral bleaching the region has ever seen. (AP Photo/Brian Skoloff)

This Sept. 13, 2019 photo shows a chunk of bleached, dead coral shown on a wall near a bay on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawaii. One of the state's most vibrant coral reefs thrives just below the surface in a bay on the west coast of Hawaii's Big Island. Qui, on a remote shoreline far from the impacts of sunscreen and throngs of tourists, scientists see the early signs of what's expected to be a catastrophic season of coral bleaching in Hawaii. The ocean here is about three and a half degrees above normal for this time of year. Coral can recover from bleaching, but when it is exposed to heat over several years, the likelihood of survival decreases. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 13, 2019 foto, ecologist Greg Asner, the director of Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, reviews ocean temperature data at his lab on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawaii. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " said Asner after a dive in Papa Bay. (AP Photo/Caleb Jones)

In questo 16 settembre, 2019 foto, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration oceanographer Jamison Gove talks about coral bleaching at the NOAA regional office in Honolulu. U.S. federal researchers in Hawaii say ocean temperatures around the archipelago are on track to match or even surpass records set in 2015, the hottest year on record for the Pacific Ocean. They predict that heat will cause some of the worst coral bleaching and mortality the region has ever seen. (Foto AP/Caleb Jones)

In this Sept. 13, 2019 foto, ecologist Greg Asner, the director of Arizona State University's Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, reviews ocean temperature data at his lab on the west coast of the Big Island near Captain Cook, Hawaii. "Nearly every species that we monitor has at least some bleaching, " said Asner after a dive in Papa Bay. (AP Photo/Caleb Jones)

The bay suffered widespread bleaching and coral death in 2015.

"It was devastating for us to not be able to do anything, " Punihaole Kennedy said. "We just watched the corals die."

© 2019 The Associated Press. Tutti i diritti riservati.