Concetto minerario di asteroidi. Credito:NASA/Denise Watt

Nel 2015, l'amministrazione Obama ha firmato l'U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act (CSLCA, o H.R. 2262) in legge. Questo disegno di legge aveva lo scopo di "facilitare un ambiente favorevole alla crescita per l'industria spaziale commerciale in via di sviluppo" rendendo legale per le aziende e i cittadini americani di possedere e vendere risorse che estraggono da asteroidi e luoghi fuori dal mondo (come la luna, Marte o oltre).

Il 6 aprile, l'amministrazione Trump ha fatto un ulteriore passo avanti firmando un ordine esecutivo che riconosce formalmente i diritti degli interessi privati di rivendicare risorse nello spazio. Quest'ordine, dal titolo "Incoraggiamento del sostegno internazionale per il recupero e l'uso delle risorse spaziali, " conclude di fatto il dibattito decennale iniziato con la firma del Trattato sullo spazio extraatmosferico nel 1967.

Questo ordine si basa sia sulla CSLCA che sulla direttiva spaziale-1 (SD-1), che l'amministrazione Trump ha firmato in legge l'11 dicembre, 2017. Stabilisce che "gli americani dovrebbero avere il diritto di impegnarsi in esplorazioni commerciali, recupero, e l'uso delle risorse nello spazio esterno, coerente con la legge applicabile, " e che gli Stati Uniti non vedono lo spazio come un "bene comune globale".

Il Trattato sullo spazio extraatmosferico

Questo ordine pone fine a decenni di ambiguità riguardo alle attività commerciali nello spazio, che tecnicamente non erano affrontati dai trattati sullo spazio esterno o sulla luna. L'ex, formalmente noto come "Trattato sui principi che regolano le attività degli Stati nell'esplorazione e nell'uso dello spazio extraatmosferico, compresi la Luna e gli altri corpi celesti", è stato firmato dagli Stati Uniti, l'Unione Sovietica, e il Regno Unito nel 1967 al culmine della Space Race.

Il razzo Saturn V dell'Apollo 11 prima del lancio il 16 luglio 1969. Screenshot dal documentario del 1970 "Moonwalk One". Credito:NASA/Theo Kamecke/YouTube

Lo scopo era quello di fornire un quadro comune che governasse le attività di tutte le maggiori potenze nello spazio. Oltre a vietare il posizionamento o la sperimentazione di armi nucleari nello spazio, il Trattato sullo spazio esterno stabilì che l'esplorazione e l'uso dello spazio esterno sarebbero stati effettuati a beneficio "di tutta l'umanità".

A partire da giugno 2019, il trattato è stato firmato da non meno di 109 paesi, mentre altri 23 lo hanno firmato ma non hanno ancora completato il processo di ratifica. Allo stesso tempo, c'è stato un dibattito in corso sul pieno significato e le implicazioni del trattato. Nello specifico, L'articolo II del trattato recita:"Lo spazio esterno, compresa la luna e altri corpi celesti, non è soggetto ad appropriazione nazionale per rivendicazione di sovranità, per uso o occupazione, o con qualsiasi altro mezzo".

Poiché la lingua è specifica della proprietà nazionale, non c'è mai stato un consenso legale sul fatto che i divieti del trattato si applichino o meno all'appropriazione privata, anche. A causa di ciò, c'è chi sostiene che i diritti di proprietà dovrebbero essere riconosciuti sulla base della giurisdizione piuttosto che della sovranità territoriale.

Il Trattato della Luna

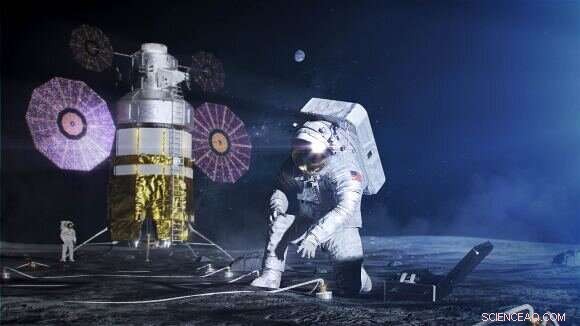

Illustrazione artistica della nuova tuta spaziale che la NASA sta progettando per gli astronauti di Artemis. Si chiama xEMU, , o Unità di Mobilità Extraveicolare Esplorativa. Credito:NASA

I tentativi di affrontare questa ambiguità hanno portato le Nazioni Unite a redigere l'"Accordo che disciplina le attività degli Stati sulla Luna e altri corpi celesti" supplementare, noto anche come "Trattato sulla luna" o "Accordo sulla luna". Come il Trattato sullo spazio extraatmosferico, questo accordo prevedeva che la luna dovesse essere utilizzata a beneficio di tutta l'umanità e che le attività non scientifiche fossero disciplinate da un quadro internazionale.

Però, ad oggi, solo 18 paesi hanno ratificato il Trattato sulla Luna, che non include gli Stati Uniti, Russia, o qualsiasi altra grande potenza nello spazio (ad eccezione dell'India). Inoltre, solo 17 dei 95 Stati membri che hanno firmato il Trattato sullo spazio esterno sono diventati firmatari del Trattato sulla Luna. Quest'ultimo ordine, intitolato "Ordine esecutivo sull'incoraggiamento del sostegno internazionale per il recupero e l'uso delle risorse spaziali, "risponde proprio a questo problema, affermando:

"L'incertezza sul diritto al recupero e all'utilizzo delle risorse spaziali, compresa l'estensione del diritto al recupero commerciale e all'uso delle risorse lunari, però, ha scoraggiato alcune entità commerciali dal partecipare a questa impresa. Le domande sul fatto che l'Accordo del 1979 che disciplina le attività degli Stati sulla Luna e sugli altri corpi celesti (l'"Accordo sulla Luna") stabilisca il quadro giuridico per gli stati nazionali in merito al recupero e all'uso delle risorse spaziali abbiano approfondito questa incertezza, soprattutto perché gli Stati Uniti non hanno né firmato né ratificato l'Accordo sulla Luna".

L'amministrazione ritiene che questo atto sia complementare all'SD-1, che sottolinea l'importanza dei partner commerciali nel Progetto Artemis e nel piano della NASA per esplorare Marte e oltre. "Esplorazione a lungo termine di successo e scoperta scientifica della luna, Marte, e altri corpi celesti richiederanno la collaborazione con entità commerciali per recuperare e utilizzare le risorse, compresa l'acqua e alcuni minerali, nello spazio esterno, " recita la direttiva.

Ritorno sulla luna

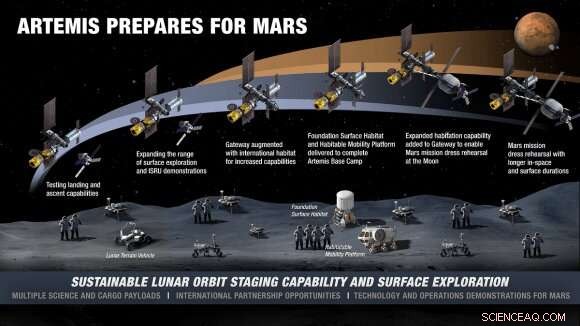

Infografica dell'evoluzione delle attività lunari in superficie e in orbita. Credito:NASA

Dopo che Artemide III ha raggiunto l'obiettivo tanto atteso di inviare i primi astronauti sulla luna dalla fine dell'era Apollo, I piani della NASA si sposteranno verso l'obiettivo a lungo termine di creare un "programma sostenibile" di esplorazione lunare. Ciò includerà la creazione del Lunar Gateway (un habitat orbitale) e del Lunar Base Camp sulla superficie della luna.

These two habitats and research stations will allow for long-term stays on the moon, a wide array of scientific experiments, and even the ability to conduct on-site refueling. Combined with a reusable lunar lander, lunar rovers and other non-expendable elements, they will also facilitate regular missions to the moon and an overall reduction in costs.

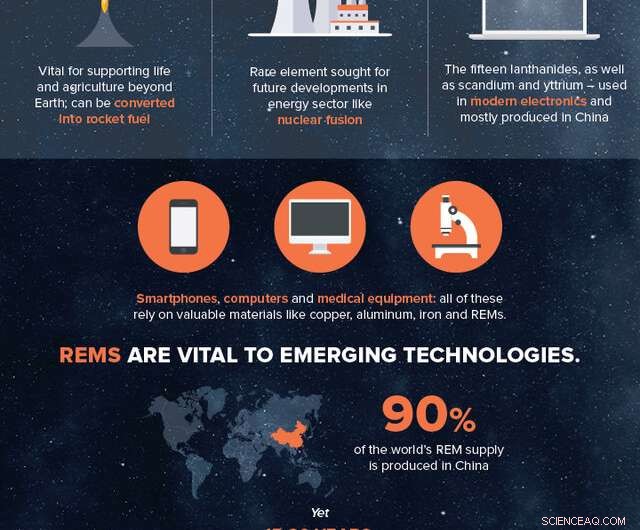

Per anni, prospectors and space mining companies like Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries have been advocating for reforms that would allow for the commercial exploitation of space. Allo stesso modo, people like Peter Diamandis (founder of X Prize and HeroX) and science communicator Neil DeGrasse Tyson have been saying for years that the first trillionaires will make their fortunes from asteroid mining.

Incidentally, NASA and HeroX recently launched the "Honey, I Shrunk the NASA Payload" challenge, which is offering $160, 000 to the team that can come up with a solution to miniaturize payloads to the point where they are "similar in size to a new bar of soap"—100 x 100 x 50 mm (3.9 x 3.9 x 1.9 inches) and weighing no more than 0.4 kg (0.8 lbs).

The purpose of this challenge is to significantly reduce the cost of sending payloads to the moon in support of future lunar missions. Però, it could also enable a new generation of mini-rovers that would explore the lunar surface for resources. As the hosts indicate on the challenge site:

The JPL-led challenge is seeking tiny payloads no larger than a bar of soap for a miniaturized Moon rover. Credito:NASA

"We need to develop practical and affordable ways to identify and use lunar resources so that our astronaut crews can become more independent of Earth… Imagine a rover the size of your Roomba crawling the moon's surface. These small rovers developed by NASA and commercial partners provide greater mission flexibility and allow NASA to collect key information about the lunar surface."

It is not hard to imagine at all that miniature rover's would also enable commercial entities the ability to explore asteroids and the lunar surface for resources that could be harvested and processed for export back to Earth. Però, not everyone is so excited by this recent move or the prospects that it entails.

Dissenting Views

Infatti, Russia's space agency (Roscosmos) officially condemned the executive order and likened it to colonialism. These sentiments were summed up in a statement issued by Sergey Saveliev, Roscosmos' deputy director-general on international cooperation:

"Attempts to expropriate outer space and aggressive plans to actually seize territories of other planets hardly set the countries (on course for) fruitful cooperation. There have already been examples in history when one country decided to start seizing territories in its interest—everyone remembers what came of it."

Artist’s impression of a lunar base. Credit:Newspace2060

Saveliev is hardly alone in drawing parallels between the NewSpace industry (or Space Race 2.0) and the age of imperialism (ca. 18th to 20th century). L'anno scorso, Dr. Victor Shammas of the Work Research Institute at Oslo Metropolitan University and independent scholar Tomas Holen produced a study that appeared in Palgrave Communications (a publication maintained by the journal Natura ).

Titled, "One giant leap for capitalist kind:private enterprise in outer space, " Shammas and Holen assert that the commercial exploitation of space will benefit human beings disproportionately. At the heart of this effort are Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and other Silicon Valley-billionaires that—contrary to their humanist pretenses—are looking to expand their wealth while taking advantage of the fact that there is little to no oversight in this area.

"In this regard, " they wrote, "SpaceX and related ventures are not so very different from maritime colonialists and the trader-exploiters of the British East India Company." For the record, the East India Company operated with impunity in India while it was under British rule, effectively making them the real governing authority over the nation and its people.

Credit:NASA/JPL/911Metallurgist/NeoMam Studios

Could asteroid mining, lunar mining, and other off-world concerns become the new colonialism? Could various companies staking claims to bodies, planets, and moons set off a period of conflict and cutthroat politics similar to what existed during the 18th to early 20th centuries? Or could this be the beginning of "post-scarcity" for humanity and an economic revolution?

And is this condemnation by Russian authorities merely an expression of lament because they don't feel well-positioned to take advantage and will that change if the Russian equivalent of a Musk or Bezos emerges? And what might we expect from countries like China and India that have been making significant strides in space for years?

All valid questions, and one which will have to be explored with greater energy and commitment now that the U.S. has officially declared that the moon and space are "open for business." It also wouldn't be surprising if certain charlatans try to push the whole "buy land on the moon" scam with greater vigor, pure.