Un gioco online di assemblaggio di scaffali, sviluppato come proof-of-concept. Credito:University of Southern California

Poiché i robot uniscono sempre più le forze per lavorare con gli esseri umani, dalle case di cura ai magazzini alle fabbriche, devono essere in grado di offrire un supporto proattivo. Ma prima, i robot devono imparare qualcosa che sappiamo istintivamente:come anticipare i bisogni delle persone.

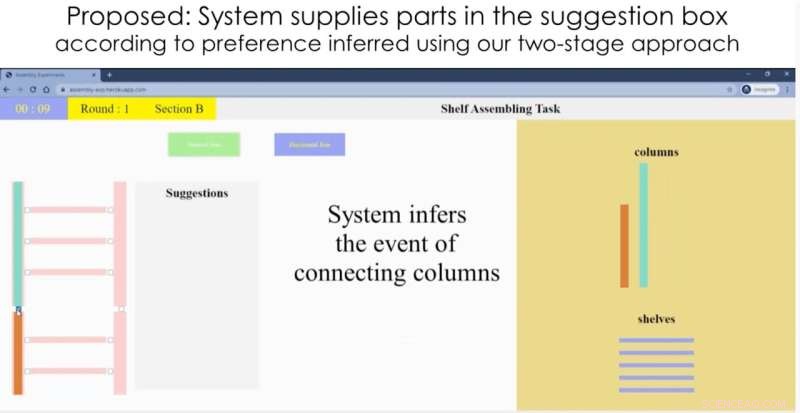

Con questo obiettivo in mente, i ricercatori della USC Viterbi School of Engineering hanno creato un nuovo sistema robotico che prevede con precisione come un essere umano costruirà una libreria IKEA e poi dà una mano, fornendo lo scaffale, il bullone o la vite necessari per completare l'attività . La ricerca è stata presentata alla Conferenza Internazionale sulla Robotica e l'Automazione il 30 maggio 2021.

"Vogliamo che l'uomo e il robot lavorino insieme:un robot può aiutarti a fare le cose più velocemente e meglio svolgendo attività di supporto, come il recupero di oggetti", ha affermato l'autore principale dello studio Heramb Nemlekar. "Gli esseri umani eseguiranno comunque le azioni primarie, ma possono scaricare le azioni secondarie più semplici sul robot."

Nemlekar, un dottorato di ricerca studente in informatica, è supervisionato da Stefanos Nikolaidis, un assistente professore di informatica, ed è coautore dell'articolo con Nikolaidis e SK Gupta, professore di ingegneria aerospaziale, meccanica e informatica che detiene la Smith International Professorship in Mechanical Engineering.

Adattamento alle variazioni

Nel 2018, un robot creato da ricercatori a Singapore ha imparato a assemblare una sedia IKEA da solo. In questo nuovo studio, il team di ricerca dell'USC mira invece a concentrarsi sulla collaborazione uomo-robot.

Ci sono vantaggi nel combinare l'intelligenza umana e la forza del robot. In una fabbrica, ad esempio, un operatore umano può controllare e monitorare la produzione, mentre il robot esegue il lavoro fisicamente faticoso. Gli esseri umani sono anche più abili in compiti complicati e delicati, come muovere una vite per adattarla.

The key challenge to overcome:humans tend to perform actions in different orders. For instance, imagine you're building a bookcase—do you tackle the easy tasks first, or go straight for the difficult ones? How does the robot helper quickly adapt to variations in its human partners?

"Humans can verbally tell the robot what they need, but that's not efficient," said Nikolaidis. "We want the robot to be able to infer what the human wants, based on some prior knowledge."

It turns out, robots can gather knowledge much like we do as humans:by "watching" people, and seeing how they behave. While we all tackle tasks in different ways, people tend to cluster around a handful of dominant preferences. If the robot can learn these preferences, it has a head start on predicting what you might do next.

A good collaborator

Based on this knowledge, the team developed an algorithm that uses artificial intelligence to classify people into dominant "preference groups," or types, based on their actions. The robot was fed a kind of "manual" on humans:data gathered from an annotated video of 20 people assembling the bookcase. The researchers found people fell into four dominant preference groups.

In an IKEA furniture assembly task, a human stayed in a “work area” and performed the assembling actions, while the robot brought the required materials from storage area. Credito:University of Southern California

For instance, do you connect all the shelves to the frame on just one side first; or do you connect each shelf to the frame on both sides, before moving onto the next shelf? Depending on your preference category, the robot should bring you a new shelf, or a new set of screws. In a real-life IKEA furniture assembly task, a human stayed in a "work area" and assembled the bookcase, while the robot—a Kinova Gen 2 robot arm—learned the human's preferences, and brought the required materials from a storage area.

"The system very quickly associates a new user with a preference, with only a few actions," said Nemlekar.

"That's what we do as humans. If I want to work to work with you, I'm not going to start from zero. I'll watch what you do, and then infer from that what you might do next."

In this initial version, the researchers entered each action into the robotic system manually, but future iterations could learn by "watching" the human partner using computer vision. The team is also working on a new test-case:humans and robots working together to build—and then fly—a model airplane, a task requiring close attention to detail.

Refining the system is a step towards having "intuitive" helper robots in our daily lives, said Nikolaidis. Although the focus is currently on collaborative manufacturing, the same insights could be used to help people with disabilities, with applications including robot-assisted eating or meal prep.

"If we will soon have robots in our homes, in our work, in care facilities, it's important for robots to infer and adapt to people's preferences," said Nikolaidis. "The robot needs to be a teammate and a good collaborator. I think having some notion of user preference and being able to learn variability is what will make robots more accepted."