Il subacqueo Lenford DaCosta pulisce le linee di corallo staghorn in un vivaio di corallo sottomarino all'interno dell'Oracbessa Fish Sanctuary, Martedì, 12 febbraio 2019, ad Oracabessa, Giamaica. Con pesce e corallo, è una relazione codipendente. I pesci si affidano alla struttura della barriera corallina per sfuggire al pericolo e deporre le uova, e divorano anche i rivali del corallo. (Foto AP/David J. Phillip)

Everton Simpson sbircia i Caraibi dal suo motoscafo, scrutando le abbaglianti bande di colore alla ricerca di indizi su ciò che si trova sotto. Il verde smeraldo indica i fondali sabbiosi. Il blu zaffiro si trova sopra i prati di alghe. E l'indaco profondo segna le barriere coralline. È lì che è diretto.

Dirige la barca verso un punto non contrassegnato che conosce come "vivaio di coralli". ''È come una foresta sotto il mare, " lui dice, allacciandosi le pinne blu e allacciandosi la bombola di ossigeno prima di ribaltarsi all'indietro nelle acque azzurre. Nuota giù per 25 piedi (7,6 metri) portando un paio di cesoie metalliche, lenza e una cassa di plastica.

Sul fondo dell'oceano, piccoli frammenti di corallo pendono da funi sospese, come calzini appesi al filo del bucato. Simpson e altri subacquei si prendono cura di questo vivaio sottomarino mentre i giardinieri si occupano di un'aiuola, strappando lentamente e faticosamente lumache e vermi che si nutrono di coralli immaturi.

Quando ogni mozzicone raggiunge le dimensioni di una mano umana, Simpson li raccoglie nella sua cassa per "trapiantarli" individualmente su una scogliera, un processo simile a piantare separatamente ogni filo d'erba in un prato.

Anche le specie di corallo in rapida crescita aggiungono solo pochi centimetri all'anno. E non è possibile spargere semplicemente i semi.

Poche ore dopo, in un sito chiamato Dickie's Reef, Simpson si tuffa di nuovo e usa pezzi di lenza per legare grappoli di corallo staghorn su affioramenti rocciosi, un legame temporaneo fino a quando lo scheletro calcareo del corallo cresce e si fissa sulla roccia. L'obiettivo è far ripartire la crescita naturale di una barriera corallina. E finora, sta funzionando.

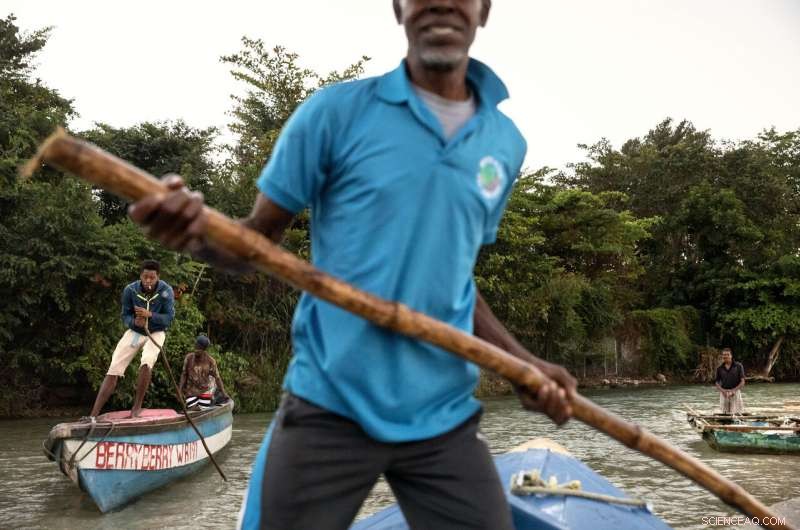

I guardiani del White River Fish Sanctuary pattugliano attraverso la barriera corallina della zona vietata al santuario a Ocho Rios, Giamaica, Martedì, 12 febbraio 2019. Dopo una serie di disastri negli anni '80 e '90, La Giamaica ha perso l'85% delle sue barriere coralline un tempo abbondanti e la sua popolazione ittica è crollata. Ma oggi, i coralli ei pesci tropicali stanno lentamente ricomparendo grazie ad alcuni attenti interventi. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Quasi tutti in Giamaica dipendono dal mare, compreso Simpson, che vive in una modesta casa che si è costruito vicino alla costa settentrionale dell'isola. L'energico 68enne si è reinventato più volte, ma si guadagnava sempre da vivere con l'oceano.

Un tempo pescatore subacqueo e poi istruttore di immersioni subacquee, Simpson ha iniziato a lavorare come "giardiniere di coralli" due anni fa, parte degli sforzi di base per riportare le barriere coralline della Giamaica dal baratro.

Le barriere coralline sono spesso chiamate "foreste pluviali del mare" per la sorprendente diversità di vita che ospitano.

Solo il 2% del fondale oceanico è pieno di coralli, ma le strutture ramificate, a forma di qualsiasi cosa, dalle corna di renna ai cervelli umani, sostengono un quarto di tutte le specie marine. Pesce pagliaccio, pesce pappagallo, cernie e dentici depongono le uova e si nascondono dai predatori negli angoli e nelle fessure della barriera corallina, e la loro presenza attira anguille, serpenti di mare, polpi e persino squali. Nelle barriere coralline sane, meduse e tartarughe marine sono visitatori abituali.

White River Fish Sanctuary custode e subacqueo Everton Simpson si dirige in mare per pattugliare contro la pesca illegale all'alba in White River, Giamaica, Martedì, 12 febbraio 2019. Una volta pescatore subacqueo e poi istruttore di immersioni subacquee, Simpson ha iniziato a lavorare come "giardiniere di coralli" e guardiano due anni fa, parte degli sforzi di base per riportare le barriere coralline della Giamaica dal baratro. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Con pesce e corallo, è una relazione codipendente:i pesci si affidano alla struttura della barriera corallina per sfuggire al pericolo e deporre le uova, e divorano anche i rivali del corallo.

La vita sul fondo dell'oceano è come una competizione al rallentatore per lo spazio, o un gioco subacqueo di sedie musicali. Pesci tropicali e altri animali marini, come ricci di mare neri, sgranocchiare alghe e alghe a crescita rapida che altrimenti potrebbero competere con il corallo a crescita lenta per lo spazio. Quando troppi pesci scompaiono, il corallo soffre e viceversa.

Dopo una serie di disastri naturali e provocati dall'uomo negli anni '80 e '90, La Giamaica ha perso l'85% delle sue barriere coralline un tempo abbondanti. Nel frattempo, le catture di pesce sono diminuite a un sesto di quelle che erano state negli anni '50, spingendo le famiglie che dipendono dai prodotti ittici più vicine alla povertà. Molti scienziati pensavano che la maggior parte della barriera corallina della Giamaica fosse stata permanentemente sostituita da alghe, come la giungla che sorpassa una cattedrale in rovina.

Il subacqueo Everton Simpson districa le linee di corallo staghorn in un vivaio di corallo all'interno del White River Fish Sanctuary lunedì, 11 febbraio 2019, a Ocho Rios, Giamaica. Sul fondo dell'oceano, piccoli frammenti di corallo pendono da funi sospese, come calzini appesi al filo del bucato. I subacquei si prendono cura di questo vivaio sottomarino come i giardinieri si occupano di un'aiuola, strappando lentamente e faticosamente lumache e vermi che si nutrono di coralli immaturi. (Foto AP/David J. Phillip)

Ma oggi, i coralli e i pesci tropicali stanno lentamente ricomparendo, grazie anche ad una serie di attenti interventi.

Il delicato lavoro del giardiniere di corallo è solo una parte del ripristino di una barriera corallina e, nonostante tutta la sua complessità, in realtà è la parte più semplice. Convincing lifelong fishermen to curtail when and where they fish and controlling the surging waste dumped into the ocean are trickier endeavors.

Ancora, slowly, the comeback effort is gaining momentum.

"The coral are coming back; the fish are coming back, " says Stuart Sandin, a marine biologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. "It's probably some of the most vibrant coral reefs we've seen in Jamaica since the 1970s."

"When you give nature a chance, she can repair herself, " he adds. "It's not too late."

Fisherman turned Oracabessa Fish Sanctuary warden and dive master, Ian Dawson, looks for fish while spearfishing outside the sanctuary's no-take zone in Oracabessa, Giamaica, Giovedi, Feb. 14, 2019. "I do fishing for a living. And right now I'm raising fish, raising fish in the sanctuary, " said Dawson who only spearfishes on his free time now when he's not working at the sanctuary enforcing the no-take zone. "If you don't put in, you can't take out, simple." (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Sandin is studying the health of coral reefs around the world as part of a research project called the "100 Island Challenge." His starting assumption was that the most populated islands would have the most degraded habitats, but what he found instead is that humans can be either a blessing or a curse, depending on how they manage resources.

In Jamaica, more than a dozen grassroots-run coral nurseries and fish sanctuaries have sprung up in the past decade, supported by small grants from foundations, local businesses such as hotels and scuba clinics, and the Jamaican government.

At White River Fish Sanctuary, which is only about 2 years old and where Simpson works, the clearest proof of early success is the return of tropical fish that inhabit the reefs, as well as hungry pelicans, skimming the surface of the water to feed on them.

Fisherman turned Oracabessa Fish Sanctuary warden and dive master, Ian Dawson, dives while spearfishing outside the sanctuary's no-take zone in Oracabessa, Giamaica, Giovedi, Feb. 14, 2019. "It was really sad because it changes everything, " said Dawson of watching Jamaica's reefs die out. "It changes livelihood for the fishermen. A lot of jobs was lost. While the fish are going away, the work going away at the same time." (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Jamaica's coral reefs were once among the world's most celebrated, with their golden branching structures and resident bright-colored fish drawing the attention of travelers from Christopher Columbus to Ian Fleming, who wrote most of his James Bond novels on the island nation's northern coast in the 1950s and '60s.

Nel 1965, the country became the site of the first global research hub for coral reefs, the Discovery Bay Marine Lab, now associated with the University of the West Indies. The pathbreaking marine biologist couple Thomas and Nora Goreau completed fundamental research here, including describing the symbiotic relationship between coral and algae and pioneering the use of scuba equipment for marine studies.

The same lab also provided a vantage point as the coral disappeared.

Peter Gayle has been a marine biologist at Discovery Bay since 1985. From the yard outside his office, he points toward the reef crest about 300 meters away—a thin brown line splashed with white waves. "Before 1980, Jamaica had healthy coral, " he notes. Then several disasters struck.

Spearfisherman Rick Walker, 35, sells his catch to a buyer at a fish market in White River, Giamaica, Martedì, Feb. 12, 2019. Walker remembers the early opposition to the fish sanctuary, with many people saying, "No, they're trying to stop our livelihood." Two years later, Camminatore, who is not involved in running the sanctuary but supports its boundary, says he can see the benefits. "It's easier to catch snapper and barracuda, " he says. "At least my great grandkids will get to see some fish." (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The first calamity was 1980's Hurricane Allen, one of the most powerful cyclones in recorded history. "Its 40-foot waves crashed against the shore and basically chewed up the reef, " Gayle says. Coral can grow back after natural disasters, but only when given a chance to recover—which it never got.

That same decade, a mysterious epidemic killed more than 95% of the black sea urchins in the Caribbean, while overfishing ravaged fish populations. And surging waste from the island's growing human population, which nearly doubled between 1960 and 2010, released chemicals and nutrients into the water that spur faster algae growth. The result:Seaweed and algae took over.

"There was a tipping point in the 1980s, when it switched from being a coral-dominated system to being an algae-dominated system, " Gayle says. "Scientists call it a 'phase shift.'"

Belinda Morrow, president of the White River Marine Association, center left, sits with fisherman turned sanctuary diver and warden, Raymond Taylor, center right, during a meeting with local fishermen about the White River Fish Sanctuary in White River, Giamaica, Lunedì, Feb. 11, 2019. Two years ago, the fishermen joined with local businesses, including hotel owners, to form a marine association and negotiate the boundaries for a no-fishing zone stretching two miles along the coast. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

That seemed like the end of the story, until an unlikely alliance started to tip the ecosystem back in the other direction, with help from residents like Everton Simpson and his fellow fisherman Lipton Bailey.

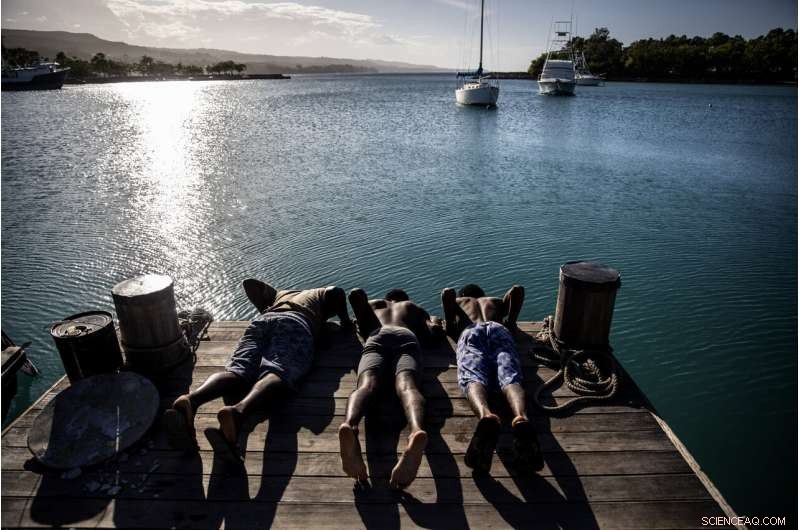

The fishing community of White River revolves around a small boat-docking area about a quarter-mile from where the river flows into the Caribbean Sea. One early morning, as purple dawn light filters into the sky, Simpson and Bailey step onto a 28-foot motorboat called the Interceptor.

Both men have lived and fished their whole lives in the community. Recentemente, they have come to believe that they need to protect the coral reefs that attract tropical fish, while setting limits on fishing to ensure the sea isn't emptied too quickly.

In the White River area, the solution was to create a protected area—a "fish sanctuary"—for immature fish to grow and reach reproductive age before they are caught.

Harold Bloomfield washes at dusk after a long day of cleaning fish in White River, Giamaica, Giovedi, Feb. 14, 2019. The delicate labor of coral gardening is only one part of restoring a reef, and for all its intricacy, it's actually the most straightforward part. Convincing lifelong fishermen to curtail when and where they fish and controlling the surging waste dumped into the ocean are trickier endeavors. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Due anni fa, the fishermen joined with local businesses, including hotel owners, to form a marine association and negotiate the boundaries for a no-fishing zone stretching two miles along the coast. A simple line in the water is hardly a deterrent, però; to make the boundary meaningful, it must be enforced. Oggi, the local fishermen, including Simpson and Bailey, take turns patrolling the boundary in the Interceptor.

On this morning, the men steer the boat just outside a row of orange buoys marked "No Fishing." ''We are looking for violators, " Bailey says, his eyes trained on the rocky coast. "Sometimes you find spearmen. They think they're smart. We try to beat them at their game."

Most of the older and more established fishermen, who own boats and set out lines and wire cages, have come to accept the no-fishing zone. Oltretutto, the risk of having their equipment confiscated is too great. But not everyone is on board. Some younger men hunt with lightweight spearguns, swimming out to sea and firing at close-range. These men—some of them poor and with few options—are the most likely trespassers.

Nicholas Bingham, sinistra, grabs his speargun while leaving the home of Gary Gooden, Giusto, as they prepare to go night spearfishing, which is banned, in Stewart Town, Giamaica, Venerdì, Feb. 15, 2019. Bingham and Gooden say they have to resort to illegal night spearfishing to make up for lost wages from the sanctuary's restrictions. Some fish sleep in the reef at night making them easier to catch than during the day. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

The patrols carry no weapons, so they must master the art of persuasion. "Let them understand this. It's not a you thing or a me thing. This isn't personal, " Bailey says of past encounters with violators.

These are sometimes risky efforts. Due anni fa, Jerlene Layne, a manager at nearby Boscobel Fish Sanctuary, landed in the hospital with a bruised leg after being attacked by a man she had reprimanded for fishing illegally in the sanctuary. "He used a stick to hit my leg because I was doing my job, telling him he cannot fish in the protected area, " lei dice.

Layne believes her work would be safer with more formal support from the police, but she isn't going to stop.

"Public mindsets can change, " she says. "If I back down on this, what kind of message does that send? You have to stand for something."

White River Fish Sanctuary warden Everton Simpson, centro, along with local fishermen, push themselves through shallow water while heading out to sea in White River, Giamaica, Martedì, Feb. 12, 2019. Simpson has lived and fished his whole life in the community. Recentemente, he has come to believe that he needs to protect the coral reefs that attract tropical fish, while setting limits on fishing to ensure the sea isn't emptied too quickly. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

She has pressed charges in court against repeat trespassers, typically resulting in a fine and equipment confiscation.

One such violator is Damian Brown, 33, who lives in a coastal neighborhood called Stewart Town. Sitting outside on a concrete staircase near his modest home, Brown says fishing is his only option for work—and he believes the sanctuary boundaries extend too far.

But others who once were skeptical say they've come to see limits as a good thing.

Back at the White River docking area, Rick Walker, a 35-year-old spearfisherman, is cleaning his motorboat. He remembers the early opposition to the fish sanctuary, with many people saying, "'No, they're trying to stop our livelihood.'"

Two years later, Camminatore, who is not involved in running the sanctuary but supports its boundary, says he can see the benefits. "It's easier to catch snapper and barracuda, " he says. "At least my great grandkids will get to see some fish."

A barbershop fills up as the sun sets in Oracabessa, Giamaica, Venerdì, Feb. 15, 2019. As Jamaica's population grew quickly between the 1950s and 1990s, the demand for seafood skyrocketed. Intense overfishing later led to plummeting catches, damaging the reef ecosystem and leaving fishermen working harder to catch smaller fish. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

When Columbus landed in Jamaica, he sailed into Oracabessa Bay, today a 20-minute drive from the mouth of the White River.

Oracabessa Bay Fish Sanctuary was the first of the grassroots-led efforts to revive Jamaica's coral reefs. Its sanctuary was legally incorporated in 2010, and its approach of enlisting local fishermen as patrols became a model for other regions.

"The fishermen are mostly on board and happy, that's the distinction. That's why it's working, " sanctuary manager Inilek Wilmot says.

David Murray, head of the Oracabessa Fishers' Association, notes that Jamaica's 60, 000 fishermen operate without a safety net. "Fishing is like gambling, è un gioco. Sometimes you catch something, sometimes you don't, " lui dice.

When fish populations began to collapse two decades ago, something had to change.

Nicholas Bingham enters the water to go night spearfishing, which is banned, in Stewart Town, Giamaica, Venerdì, Feb. 15, 2019. Bingham says he has to resort to illegal night spearfishing to make up for lost wages from the sanctuary's restrictions. "From the time I was born fishing is all I do. It's my bread and butter, " said Bingham. "There's not many other jobs to do. What am I going to do, take up a gun? (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Murray now works as a warden in the Oracabessa sanctuary, while continuing to fish outside its boundary. He also spends time explaining the concept to neighbors.

"It's people work—it's a process to get people to agree on a sanctuary boundary, " he says. "It's a tough job to tell a man who's been fishing all his life that he can't fish here."

But once it became clear that a no-fishing zone actually helped nearby fish populations rebound, it became easier to build support. The number of fish in the sanctuary has doubled between 2011 and 2017, and the individual fish have grown larger—nearly tripling in length on average—according to annual surveys by Jamaica's National Environment and Planning Agency. And that boosts catches in surrounding areas.

After word got out about Oracabessa, other regions wanted advice.

Diver Lenford DaCosta cleans up lines of staghorn coral at an underwater coral nursery inside the Oracabessa Fish Sanctuary on Tuesday, Feb. 12, 2019, in Oracabessa, Jamaica. In Jamaica, more than a dozen grassroots-run coral nurseries and fish sanctuaries have sprung up in the past decade, supported by small grants from foundations, local businesses such as hotels and scuba clinics, and the Jamaican government. (Foto AP/David J. Phillip)

Diver Everton Simpson grabs a handful of staghorn, harvested from a coral nursery, to be planted inside the the White River Fish Sanctuary Tuesday, Feb. 12, 2019, in Ocho Rios, Jamaica. When each stub grows to about the size of a human hand, Simpson collects them in his crate to individually "transplant" onto a reef, a process akin to planting each blade of grass in a lawn separately. Even fast-growing coral species add just a few inches a year. And it's not possible to simply scatter seeds. (Foto AP/David J. Phillip)

Belinda Morrow, president of the White River Marine Association, sinistra, braces herself and Charmaine Webber, with the Environmental Foundation of Jamaica, from the rocking boat as diver Raymond Bailey, Giusto, falls into the water to plant coral on a reef within the protected White River Fish Sanctuary in Ocho Rios, Giamaica, Martedì, Feb. 12, 2019. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Diver Everton Simpson plants staghorn harvested from a coral nursery inside the the White River Fish Sanctuary Tuesday, Feb. 12, 2019, in Ocho Rios, Jamaica. Simpson uses bits of fishing line to tie clusters of staghorn coral onto rocky outcroppings, a temporary binding until the coral's limestone skeleton grows and fixes itself onto the rock. The goal is to jumpstart the natural growth of a coral reef. E finora, it's working. (Foto AP/David J. Phillip)

Belinda Morrow, president of the White River Marine Association, uses a box with a glass bottom to look underwater from a boat as coral is planted on a reef within the protected White River Fish Sanctuary in Ocho Rios, Giamaica, Martedì, Feb. 12, 2019. "We all depend on the ocean, " said Morrow. "If we don't have a good healthy reef and a good healthy marine environment, we will lose too much. Too much of the country relies on the sea." (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Fisherman Oswald Coombs is encircled by tarpon as he cleans his catch on the beach in the fishing village of Oracabessa Bay, Giamaica, Mercoledì, Feb. 13, 2019. With fish and coral, it's a codependent relationship, the fish rely upon the reef structure to evade danger and lay eggs, and they also eat up the coral's rivals. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Fisherman Anthony Person, sinistra, complains to Boscobel Marine Sanctuary wardens that his fish pots are getting damaged by passing tourist boats as the wardens patrol on foot through the community in Boscobel, Giamaica, Mercoledì, Feb. 13, 2019. Most of the older and more established fishermen, who own boats and set out lines and wire cages, have come to accept the no-fishing zone. But not everyone is on board. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Morris Gause, da sinistra, Nigel Simpson and Andre Ramator, peer over the end of a dock to look at fish in the Oracabessa Fish Sanctuary, in Oracabessa Bay, Giamaica, Martedì, Feb. 12, 2019. "Most people, what they see, and why people have bought into it is walking down to the beach and looking into the water and seeing fish you know, " said sanctuary manager Inilek Wilmot. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

A vendor sells coconut water in a shopping area popular with cruise ships and tourists in Ocho Rios, Giamaica, Venerdì, Feb. 15, 2019. Jamaica's coral reefs were once among the world's most celebrated, with their golden branching structures and resident bright-colored fish drawing the attention of travelers from Christopher Columbus to Ian Fleming, who wrote most of his James Bond novels on the island nation's northern coast in the 1950s and '60s. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Fisherman Damian Brown helps his daughter Mishaunda, 9, with her homework as his sons Damian Jr., 3, da sinistra, Dre, 4, and daughter Paris, 1, Giusto, watch television in their home in Stewart Town, Giamaica, Giovedi, Feb. 14, 2019. Brown has been caught twice fishing inside a no-take zone and now relies more on night spearfishing, which is illegal, to make up for the wages impacted by the sanctuary's restrictions. "Was nice before the sanctuary come in. Was good, " said Brown. "Now I make no money off the sea again like one time." (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Nicholas Bingham spearfishes at night, which is banned, in Stewart Town, Giamaica, Venerdì, Feb. 15, 2019. Bingham says he has to resort to illegal night spearfishing to make up for lost wages from the sanctuary's restrictions. Getting caught can mean a fine, confiscation of equipment and even imprisonment. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

White River Fish Sanctuary warden Mark Lobban shines a spotlight on the protected reef while patrolling the no-take zone for illegal fishermen under moonlight in Ocho Rios, Giamaica, Venerdì, Feb. 15, 2019. Most of the older and more established fishermen, who own boats and set out lines and wire cages, have come to accept the no-fishing zone. Some younger men though, some of them poor and with few options, are the most likely trespassers. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Fisherman turned Oracabessa Fish Sanctuary warden and dive master, Ian Dawson, gets a haircut in Oracabessa, Giamaica, Venerdì, Feb. 15, 2019. "Like the great mathematicians, pyramids, things from centuries (ago), but people still talk about it, people still relate to it, so it's good, " said Dawson of his part in protecting the fish sanctuary. "Probably years to come, that's a signature. I leave a signature here, live on with my grandchildren you know." (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Jerlene Layne, sinistra, manager of the Boscobel Marine Sanctuary, talks with repeat violator, fisherman Damian Brown, while patrolling on foot through the community in Stewart Town, Giamaica, Mercoledì, Feb. 13, 2019. Layne was once attacked by a man she had reprimanded for fishing illegally in the sanctuary. "Public mindsets can change, " she says. "If I back down on this, what kind of message does that send? You have to stand for something." (AP Photo/David Goldman)

A boy waits to have his hair cut after school as the sun sets in the seaside fishing town of Oracabessa, Giamaica, Venerdì, Feb. 15, 2019. Oracabessa was the first of the grassroots-led efforts to revive Jamaica's coral reefs. Its sanctuary's approach of enlisting local fishermen as patrols became a model for other regions. The sanctuary also engages with local children about the importance of keeping the beach clean. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

Jerlene Layne, manager of the Boscobel Marine Sanctuary, patrols on foot through the community in Stewart Town, Giamaica, Mercoledì, Feb. 13, 2019. Part of Layne's job is to engage with local fisherman and listen to their concerns regarding the sanctuary's no-take zone. "What I love about my job is actually the opportunity to give back to the environment by protecting it, " said Layne. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

A boat heads out to sea at dawn from the fishing village of White River, Giamaica, Giovedi, Feb. 14, 2019. Two years ago in White River, fishermen joined with local businesses, including hotel owners, to form a marine association and negotiate the boundaries for a no-fishing zone stretching two miles along the coast for immature fish to grow and reach reproductive age before they are caught. (Foto AP/David Goldman)

"We have the data to show success, but even more important than data is word of mouth, " says Wilmot, who oversaw training to help start the fish sanctuary at White River.

Belinda Morrow, a lifelong water-sports enthusiast often seen paddle-boarding with her dog Shadow, runs the White River Marine Association. She attends fishers' meetings and raises small grants from the Jamaican government and other foundations to support equipment purchases and coral replanting campaigns.

"We all depend on the ocean, " Morrow says, sitting in a small office decorated with nautical maps in the iconic 70-year-old Jamaica Inn. "If we don't have a good healthy reef and a good healthy marine environment, we will lose too much. Too much of the country relies on the sea."

© 2019 The Associated Press. Tutti i diritti riservati.