Una foresta pluviale tropicale in Sud America. Credito:Shutterstock/BorneoRimbawan

Una mattina del 2009, Mi sono seduto su un autobus scricchiolante che serpeggiava su per una montagna nel centro del Costa Rica, stordito dai fumi del diesel mentre stringevo le mie numerose valigie. Contenevano migliaia di provette e fiale di campioni, uno spazzolino, un taccuino impermeabile e due cambi di vestiti.

Stavo andando alla Stazione Biologica La Selva, dove avrei passato diversi mesi a studiare il bagnato, risposta della foresta pluviale di pianura a siccità sempre più comuni. Su entrambi i lati della stretta autostrada, gli alberi sanguinavano nella nebbia come gli acquerelli sulla carta, dando l'impressione di un'infinita foresta primordiale bagnata dalle nuvole.

Mentre guardavo fuori dalla finestra il paesaggio imponente, Mi chiedevo come avrei mai potuto sperare di capire un paesaggio così complesso. Sapevo che migliaia di ricercatori in tutto il mondo erano alle prese con le stesse domande, cercando di capire il destino delle foreste tropicali in un mondo in rapida evoluzione.

La nostra società chiede tanto a questi fragili ecosistemi, che controllano la disponibilità di acqua dolce per milioni di persone e ospitano i due terzi della biodiversità terrestre del pianeta. E sempre più, abbiamo posto una nuova richiesta su queste foreste, per salvarci dal cambiamento climatico causato dall'uomo.

Le piante assorbono CO 2 dall'atmosfera, trasformandolo in foglie, legno e radici. Questo miracolo quotidiano ha stimolato la speranza che le piante, in particolare gli alberi tropicali a crescita rapida, possano agire come un freno naturale ai cambiamenti climatici, catturando gran parte della CO 2 emessi dalla combustione di combustibili fossili. Attraverso il mondo, governi, le aziende e gli enti di beneficenza per la conservazione si sono impegnati a conservare o piantare un numero enorme di alberi.

Ma il fatto è che non ci sono abbastanza alberi per compensare le emissioni di carbonio della società, e non ci saranno mai. Di recente ho condotto una revisione della letteratura scientifica disponibile per valutare quanto carbonio potrebbero effettivamente assorbire le foreste. Se massimizzassimo assolutamente la quantità di vegetazione che tutta la terra sulla Terra potrebbe contenere, sequestreremmo abbastanza carbonio per compensare circa dieci anni di emissioni di gas serra ai tassi attuali. Dopo di che, non potrebbe esserci un ulteriore aumento della cattura del carbonio.

Eppure il destino della nostra specie è indissolubilmente legato alla sopravvivenza delle foreste e alla biodiversità che contengono. Correndo a piantare milioni di alberi per la cattura del carbonio, potremmo inavvertitamente danneggiare le stesse proprietà forestali che le rendono così vitali per il nostro benessere? Per rispondere a questa domanda, dobbiamo considerare non solo come le piante assorbono CO 2 , ma anche come forniscono le solide fondamenta verdi per gli ecosistemi sulla terraferma.

Come le piante combattono il cambiamento climatico

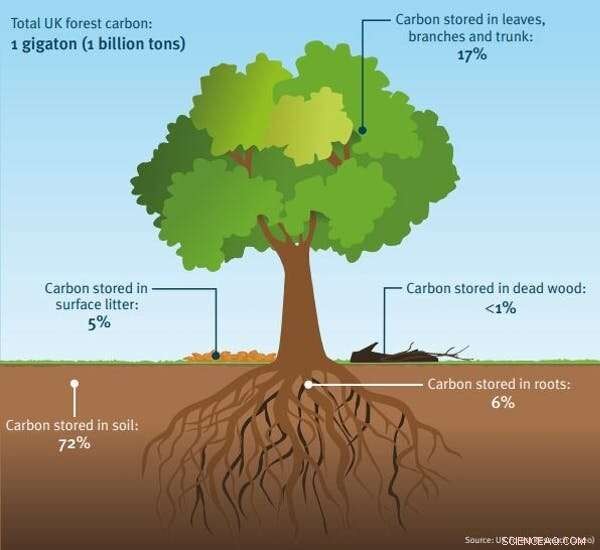

Gli impianti convertono CO 2 gas in zuccheri semplici in un processo noto come fotosintesi. Questi zuccheri vengono quindi utilizzati per costruire i corpi viventi delle piante. Se il carbonio catturato finisce nel legno, può essere tenuto lontano dall'atmosfera per molti decenni. Quando le piante muoiono, i loro tessuti vanno incontro a decomposizione e vengono incorporati nel terreno.

Bonnie Waring conduce ricerche presso la Stazione Biologica La Selva, Costa Rica, 2011. Autore fornito

Mentre questo processo rilascia naturalmente CO 2 attraverso la respirazione (o respirazione) di microbi che decompongono gli organismi morti, una parte del carbonio vegetale può rimanere nel sottosuolo per decenni o addirittura secoli. Insieme, piante terrestri e suoli contengono circa 2, 500 gigatonnellate di carbonio, circa tre volte di più di quello contenuto nell'atmosfera.

Poiché le piante (soprattutto gli alberi) sono dei depositi naturali eccellenti per il carbonio, ha senso che aumentare l'abbondanza di piante in tutto il mondo potrebbe ridurre la CO . atmosferica 2 concentrazioni.

Le piante hanno bisogno di quattro ingredienti fondamentali per crescere:luce, CO 2 , acqua e sostanze nutritive (come azoto e fosforo, gli stessi elementi presenti nel fertilizzante vegetale). Migliaia di scienziati in tutto il mondo studiano come varia la crescita delle piante in relazione a questi quattro ingredienti, per prevedere come la vegetazione risponderà ai cambiamenti climatici.

Questo è un compito sorprendentemente impegnativo, dato che gli esseri umani stanno modificando contemporaneamente tanti aspetti dell'ambiente naturale riscaldando il globo, alterare i modelli di pioggia, tagliando grandi tratti di foresta in minuscoli frammenti e introducendo specie aliene a cui non appartengono. Ci sono anche oltre 350, 000 specie di piante da fiore sulla terra e ognuna risponde alle sfide ambientali in modi unici.

A causa dei complicati modi in cui gli umani stanno alterando il pianeta, c'è molto dibattito scientifico sulla quantità precisa di carbonio che le piante possono assorbire dall'atmosfera. Ma i ricercatori sono d'accordo unanime sul fatto che gli ecosistemi terrestri hanno una capacità finita di assorbire carbonio.

Se assicuriamo che gli alberi abbiano abbastanza acqua da bere, le foreste cresceranno alte e rigogliose, creando baldacchini ombrosi che affamano gli alberi più piccoli di luce. Se aumentiamo la concentrazione di CO 2 nell'aria, le piante lo assorbiranno avidamente, fino a quando non saranno più in grado di estrarre abbastanza fertilizzante dal terreno per soddisfare i loro bisogni. Proprio come un fornaio che fa una torta, le piante richiedono CO 2 , azoto e fosforo in rapporti particolari, seguendo una specifica ricetta di vita.

In riconoscimento di questi vincoli fondamentali, gli scienziati stimano che gli ecosistemi terrestri della terra possono contenere abbastanza vegetazione aggiuntiva per assorbire tra le 40 e le 100 gigatonnellate di carbonio dall'atmosfera. Una volta raggiunta questa ulteriore crescita (un processo che richiederà alcuni decenni), non c'è capacità di stoccaggio aggiuntivo di carbonio a terra.

Ma la nostra società sta attualmente versando CO 2 nell'atmosfera a una velocità di dieci gigatonnellate di carbonio all'anno. I processi naturali faranno fatica a tenere il passo con il diluvio di gas serra generati dall'economia globale. Per esempio, Ho calcolato che un singolo passeggero su un volo di andata e ritorno da Melbourne a New York City emetterà circa il doppio di carbonio (1600 kg C) di quello contenuto in una quercia di mezzo metro di diametro (750 kg C).

Foglia al microscopio:si vede lo stoma che regola l'ossigeno e l'anidride carbonica. Credito:Shutterstock/Barbol

Pericolo e promessa

Nonostante tutti questi vincoli fisici ben riconosciuti sulla crescita delle piante, c'è un numero crescente di sforzi su larga scala per aumentare la copertura vegetale per mitigare l'emergenza climatica, una cosiddetta soluzione climatica "basata sulla natura". La stragrande maggioranza di questi sforzi si concentra sulla protezione o sull'espansione delle foreste, poiché gli alberi contengono molte volte più biomassa rispetto agli arbusti o alle erbe e rappresentano quindi un maggiore potenziale di cattura del carbonio.

Eppure i fraintendimenti fondamentali sulla cattura del carbonio da parte degli ecosistemi terrestri possono avere conseguenze devastanti, con conseguente perdita di biodiversità e aumento di CO 2 concentrazioni. Sembra un paradosso:in che modo piantare alberi può avere un impatto negativo sull'ambiente?

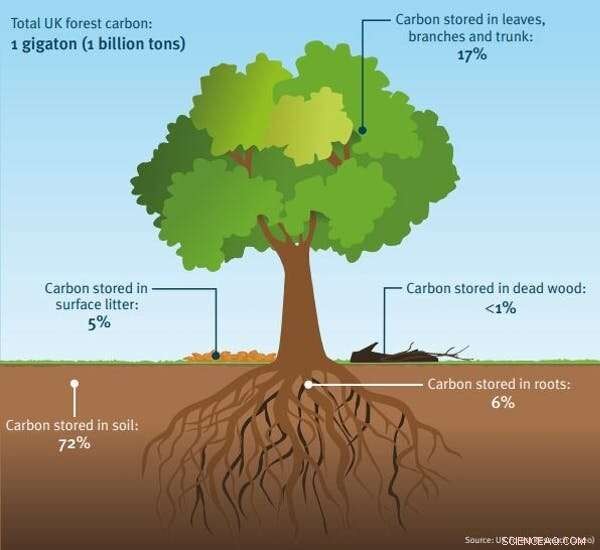

La risposta sta nelle sottili complessità della cattura del carbonio negli ecosistemi naturali. Per evitare danni ambientali, dobbiamo astenerci dallo stabilire foreste dove naturalmente non appartengono, evitare "incentivi perversi" a tagliare la foresta esistente per piantare nuovi alberi, e considerare come potrebbero comportarsi le piantine piantate oggi nei prossimi decenni.

Prima di intraprendere qualsiasi espansione dell'habitat forestale, dobbiamo garantire che gli alberi siano piantati nel posto giusto perché non tutti gli ecosistemi sulla terra possono o devono supportare gli alberi. Piantare alberi in ecosistemi che sono normalmente dominati da altri tipi di vegetazione spesso non riesce a provocare il sequestro del carbonio a lungo termine.

Un esempio particolarmente illustrativo viene dalle torbiere scozzesi, vaste aree di terreno dove la vegetazione bassa (per lo più muschi ed erbe) cresce in un ambiente costantemente inzuppato, terreno umido. Poiché la decomposizione è molto lenta nei terreni acidi e impregnati d'acqua, le piante morte si accumulano in periodi di tempo molto lunghi, creare torba. Non è solo la vegetazione a essere preservata:le torbiere mummificano anche i cosiddetti "corpi di palude", i resti quasi intatti di uomini e donne morti millenni fa. Infatti, Le torbiere del Regno Unito contengono 20 volte più carbonio di quello che si trova nelle foreste della nazione.

Ma alla fine del XX secolo, alcune paludi scozzesi sono state prosciugate per piantare alberi. L'essiccazione del terreno ha permesso alle piantine di alberi di stabilirsi, ma ha anche accelerato il decadimento della torba. L'ecologista Nina Friggens e i suoi colleghi dell'Università di Exeter hanno stimato che la decomposizione della torba essiccata ha rilasciato più carbonio di quanto gli alberi in crescita potessero assorbire. Chiaramente, le torbiere possono salvaguardare al meglio il clima quando sono lasciate a se stesse.

Lo stesso vale per le praterie e le savane, dove gli incendi sono una parte naturale del paesaggio e spesso bruciano alberi piantati dove non appartengono. Questo principio si applica anche alle tundre artiche, dove la vegetazione autoctona è ricoperta di neve per tutto l'inverno, riflettendo luce e calore nello spazio. Piantare in alto, gli alberi dalle foglie scure in queste aree possono aumentare l'assorbimento di energia termica, e portare al riscaldamento locale.

But even planting trees in forest habitats can lead to negative environmental outcomes. From the perspective of both carbon sequestration and biodiversity, all forests are not equal—naturally established forests contain more species of plants and animals than plantation forests. They often hold more carbon, pure. But policies aimed at promoting tree planting can unintentionally incentivise deforestation of well established natural habitats.

Where carbon is stored in a typical temperate forest in the UK. Credit:UK Forest Research, CC BY

A recent high-profile example concerns the Mexican government's Sembrando Vida program, which provides direct payments to landowners for planting trees. The problem? Many rural landowners cut down well established older forest to plant seedlings. This decision, while quite sensible from an economic point of view, has resulted in the loss of tens of thousands of hectares of mature forest.

This example demonstrates the risks of a narrow focus on trees as carbon absorption machines. Many well meaning organizations seek to plant the trees which grow the fastest, as this theoretically means a higher rate of CO 2 "drawdown" from the atmosphere.

Yet from a climate perspective, what matters is not how quickly a tree can grow, but how much carbon it contains at maturity, and how long that carbon resides in the ecosystem. As a forest ages, it reaches what ecologists call a "steady state"—this is when the amount of carbon absorbed by the trees each year is perfectly balanced by the CO 2 released through the breathing of the plants themselves and the trillions of decomposer microbes underground.

This phenomenon has led to an erroneous perception that old forests are not useful for climate mitigation because they are no longer growing rapidly and sequestering additional CO 2 . The misguided "solution" to the issue is to prioritize tree planting ahead of the conservation of already established forests. This is analogous to draining a bathtub so that the tap can be turned on full blast:the flow of water from the tap is greater than it was before—but the total capacity of the bath hasn't changed. Mature forests are like bathtubs full of carbon. They are making an important contribution to the large, but finite, quantity of carbon that can be locked away on land, and there is little to be gained by disturbing them.

What about situations where fast growing forests are cut down every few decades and replanted, with the extracted wood used for other climate-fighting purposes? While harvested wood can be a very good carbon store if it ends up in long lived products (like houses or other buildings), surprisingly little timber is used in this way.

Allo stesso modo, burning wood as a source of biofuel may have a positive climate impact if this reduces total consumption of fossil fuels. But forests managed as biofuel plantations provide little in the way of protection for biodiversity and some research questions the benefits of biofuels for the climate in the first place.

Fertilize a whole forest

Scientific estimates of carbon capture in land ecosystems depend on how those systems respond to the mounting challenges they will face in the coming decades. All forests on Earth—even the most pristine—are vulnerable to warming, changes in rainfall, increasingly severe wildfires and pollutants that drift through the Earth's atmospheric currents.

Some of these pollutants, però, contain lots of nitrogen (plant fertilizer) which could potentially give the global forest a growth boost. By producing massive quantities of agricultural chemicals and burning fossil fuels, humans have massively increased the amount of "reactive" nitrogen available for plant use. Some of this nitrogen is dissolved in rainwater and reaches the forest floor, where it can stimulate tree growth in some areas.

Implications of large-scale tree planting in various climatic zones and ecosystems. Credit:Stacey McCormack/Köppen climate classification, Autore fornito

As a young researcher fresh out of graduate school, I wondered whether a type of under-studied ecosystem, known as seasonally dry tropical forest, might be particularly responsive to this effect. There was only one way to find out:I would need to fertilize a whole forest.

Working with my postdoctoral adviser, the ecologist Jennifer Powers, and expert botanist Daniel Pérez Avilez, I outlined an area of the forest about as big as two football fields and divided it into 16 plots, which were randomly assigned to different fertilizer treatments. For the next three years (2015-2017) the plots became among the most intensively studied forest fragments on Earth. We measured the growth of each individual tree trunk with specialised, hand-built instruments called dendrometers.

We used baskets to catch the dead leaves that fell from the trees and installed mesh bags in the ground to track the growth of roots, which were painstakingly washed free of soil and weighed. The most challenging aspect of the experiment was the application of the fertilizers themselves, which took place three times a year. Wearing raincoats and goggles to protect our skin against the caustic chemicals, we hauled back-mounted sprayers into the dense forest, ensuring the chemicals were evenly applied to the forest floor while we sweated under our rubber coats.

Sfortunatamente, our gear didn't provide any protection against angry wasps, whose nests were often concealed in overhanging branches. Ma, our efforts were worth it. After three years, we could calculate all the leaves, wood and roots produced in each plot and assess carbon captured over the study period. We found that most trees in the forest didn't benefit from the fertilizers—instead, growth was strongly tied to the amount of rainfall in a given year.

This suggests that nitrogen pollution won't boost tree growth in these forests as long as droughts continue to intensify. To make the same prediction for other forest types (wetter or drier, younger or older, warmer or cooler) such studies will need to be repeated, adding to the library of knowledge developed through similar experiments over the decades. Yet researchers are in a race against time. Experiments like this are slow, painstaking, sometimes backbreaking work and humans are changing the face of the planet faster than the scientific community can respond.

Humans need healthy forests

Supporting natural ecosystems is an important tool in the arsenal of strategies we will need to combat climate change. But land ecosystems will never be able to absorb the quantity of carbon released by fossil fuel burning. Rather than be lulled into false complacency by tree planting schemes, we need to cut off emissions at their source and search for additional strategies to remove the carbon that has already accumulated in the atmosphere.

Does this mean that current campaigns to protect and expand forest are a poor idea? Emphatically not. The protection and expansion of natural habitat, particularly forests, is absolutely vital to ensure the health of our planet. Forests in temperate and tropical zones contain eight out of every ten species on land, yet they are under increasing threat. Nearly half of our planet's habitable land is devoted to agriculture, and forest clearing for cropland or pasture is continuing apace.

Nel frattempo, the atmospheric mayhem caused by climate change is intensifying wildfires, worsening droughts and systematically heating the planet, posing an escalating threat to forests and the wildlife they support. What does that mean for our species? Again and again, researchers have demonstrated strong links between biodiversity and so-called "ecosystem services"—the multitude of benefits the natural world provides to humanity.

Dendrometer devices wrapped around tree trunks to measure growth. Autore fornito

Carbon capture is just one ecosystem service in an incalculably long list. Biodiverse ecosystems provide a dizzying array of pharmaceutically active compounds that inspire the creation of new drugs. They provide food security in ways both direct (think of the millions of people whose main source of protein is wild fish) and indirect (for example, a large fraction of crops are pollinated by wild animals).

Natural ecosystems and the millions of species that inhabit them still inspire technological developments that revolutionize human society. Per esempio, take the polymerase chain reaction ("PCR") that allows crime labs to catch criminals and your local pharmacy to provide a COVID test. PCR is only possible because of a special protein synthesized by a humble bacteria that lives in hot springs.

As an ecologist, I worry that a simplistic perspective on the role of forests in climate mitigation will inadvertently lead to their decline. Many tree planting efforts focus on the number of saplings planted or their initial rate of growth—both of which are poor indicators of the forest's ultimate carbon storage capacity and even poorer metric of biodiversity. Ma ancora più importante, viewing natural ecosystems as "climate solutions" gives the misleading impression that forests can function like an infinitely absorbent mop to clean up the ever increasing flood of human caused CO 2 emissioni.

Per fortuna, many big organizations dedicated to forest expansion are incorporating ecosystem health and biodiversity into their metrics of success. A little over a year ago, I visited an enormous reforestation experiment on the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, operated by Plant-for-the-Planet—one of the world's largest tree planting organizations. After realizing the challenges inherent in large scale ecosystem restoration, Plant-for-the-Planet has initiated a series of experiments to understand how different interventions early in a forest's development might improve tree survival.

But that is not all. Led by Director of Science Leland Werden, researchers at the site will study how these same practices can jump-start the recovery of native biodiversity by providing the ideal environment for seeds to germinate and grow as the forest develops. These experiments will also help land managers decide when and where planting trees benefits the ecosystem and where forest regeneration can occur naturally.

Viewing forests as reservoirs for biodiversity, rather than simply storehouses of carbon, complicates decision making and may require shifts in policy. I am all too aware of these challenges. I have spent my entire adult life studying and thinking about the carbon cycle and I too sometimes can't see the forest for the trees. One morning several years ago, I was sitting on the rainforest floor in Costa Rica measuring CO 2 emissions from the soil—a relatively time intensive and solitary process.

As I waited for the measurement to finish, I spotted a strawberry poison dart frog—a tiny, jewel-bright animal the size of my thumb—hopping up the trunk of a nearby tree. Intrigued, I watched her progress towards a small pool of water held in the leaves of a spiky plant, in which a few tadpoles idly swam. Once the frog reached this miniature aquarium, the tiny tadpoles (her children, as it turned out) vibrated excitedly, while their mother deposited unfertilised eggs for them to eat. As I later learned, frogs of this species (Oophaga pumilio) take very diligent care of their offspring and the mother's long journey would be repeated every day until the tadpoles developed into frogs.

It occurred to me, as I packed up my equipment to return to the lab, that thousands of such small dramas were playing out around me in parallel. Forests are so much more than just carbon stores. They are the unknowably complex green webs that bind together the fates of millions of known species, with millions more still waiting to be discovered. To survive and thrive in a future of dramatic global change, we will have to respect that tangled web and our place in it.

Questo articolo è stato ripubblicato da The Conversation con una licenza Creative Commons. Leggi l'articolo originale.