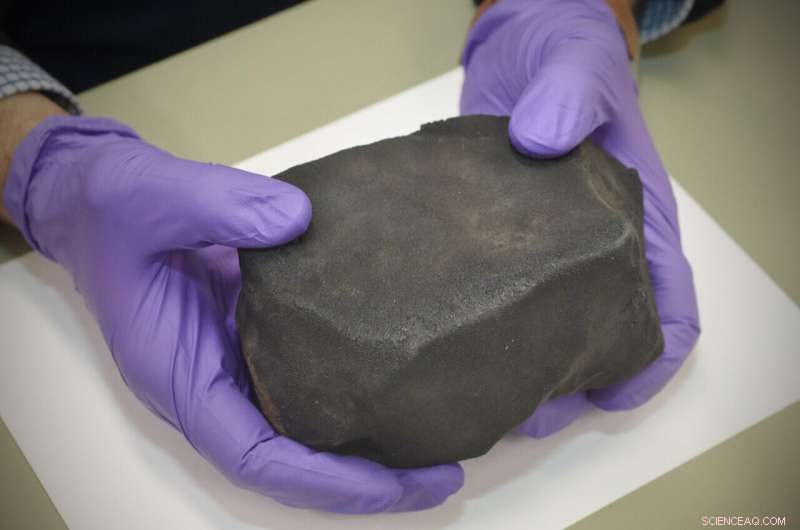

La massa principale del meteorite di Aguas Zarcas al Field Museum. Credito:John Weinstein, Field Museum

Nel 2019, la navicella spaziale OSIRIS-REx della NASA ha inviato le immagini di un fenomeno geologico che nessuno aveva mai visto prima:i ciottoli volavano dalla superficie dell'asteroide Bennu. L'asteroide sembrava sparare fuori sciami di rocce grandi come marmo. Gli scienziati non avevano mai visto questo comportamento da un asteroide prima, ed è esattamente un mistero il motivo per cui accade. Ma in un nuovo articolo su Nature Astronomy , i ricercatori mostrano la prima prova di questo processo in un meteorite.

"È affascinante vedere qualcosa che è stato appena scoperto da una missione spaziale su un asteroide a milioni di miglia dalla Terra e trovare un record dello stesso processo geologico nella collezione di meteoriti del museo", afferma Philipp Heck, curatore di Robert A. Pritzker di Meteoritics al Field Museum di Chicago e autore senior di Nature Astronomy studia.

I meteoriti sono pezzi di roccia che cadono sulla Terra dallo spazio; possono essere fatti di pezzi di lune e pianeti, ma il più delle volte sono frammenti di asteroidi spezzati. Il meteorite Aguas Zarcas prende il nome dalla città costaricana dove è caduto nel 2019; è arrivato al Field Museum come donazione di Terry e Gail Boudreaux. Heck e il suo studente, Xin Yang, stavano preparando il meteorite per un altro studio quando hanno notato qualcosa di strano.

"Stavamo cercando di isolare minerali molto piccoli dal meteorite congelandolo con azoto liquido e scongelandolo con acqua calda, per romperlo", afferma Yang, uno studente laureato al Field Museum e all'Università di Chicago e il primo articolo del giornale autore. "Funziona per la maggior parte dei meteoriti, ma questo era un po' strano:abbiamo trovato dei frammenti compatti che non si rompevano."

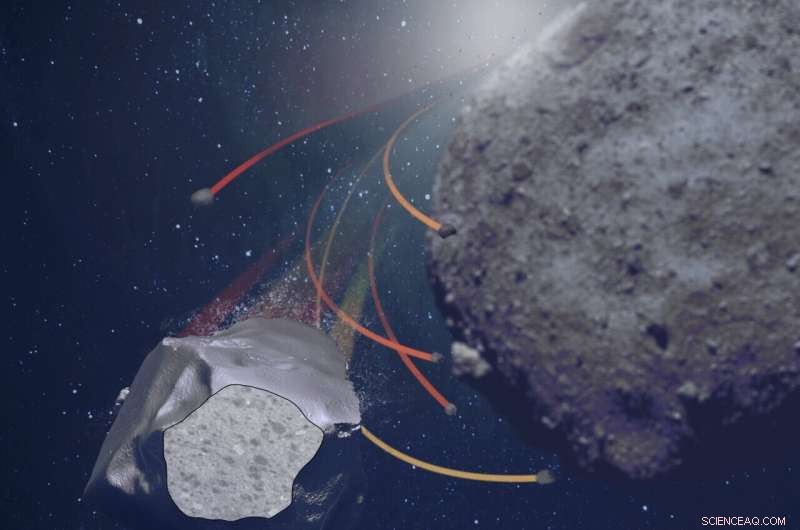

Rappresentazione artistica del processo di miscelazione dei ciottoli dal corpo genitore di Aguas Zarcas. I frammenti delle dimensioni di un ciottolo vengono espulsi e riposizionati sulla superficie dell'asteroide. Credito:aprile I. Neander. Immagine dell'asteroide:NASA/Goddard/Università dell'Arizona.

Diamine, non è raro trovare frammenti di meteorite che non si disintegrino, ma gli scienziati di solito alzano le spalle e rompono mortaio e pestello. "Xin aveva una mente molto aperta, ha detto, 'Non ho intenzione di schiacciare questi sassi per ridurli in sabbia, questo è interessante'", dice Heck. Invece, i ricercatori hanno escogitato un piano per capire cosa fossero questi ciottoli e perché erano così resistenti alla rottura.

"We did CT scans to see how the pebbles compared to the other rocks making up the meteorite," says Heck. "What was striking is that these components were all squished— normally, they'd be spherical— and they all had the same orientation. They were all deformed in the same direction, by one process." Something had happened to the pebbles that didn't happen to the rest of the rock around them.

Pebbles ejected off the surface of asteroid Bennu were observed frequently by NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. This observation inspired this study. Credit:NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona/Lockheed Martin.

"This was exciting, we were very curious about what it meant," says Yang.

The scientists had a clue, though, from the 2019 OSIRIS-REx findings. From there, they put together a hypothesis, which they supported with physical models. The asteroid underwent a high-speed collision, and the area of impact got deformed. That deformed rock eventually broke apart due to the huge temperature differences the asteroid experiences when it rotates, since the side facing the sun is more than 300° F warmer than the side facing away. "This constant thermal cycling makes the rock brittle, and it breaks apart into gravel," says Heck.

These pebbles are then ejected from the asteroid's surface. "We don't yet know what the process is that ejects the pebbles," says Heck— they might be dislodged by smaller impacts other space collisions, or they might just get released by the thermal stress the asteroid undergoes. But once the pebbles are disturbed, Heck says, "you don't need much to eject something— the escape velocity is very low." A recent study of Bennu revealed that its surface is loosely bound and behaves like popcorn in a bucket.

Sampling of the Aguas Zarcas meteorite at the Field Museum of Natural History. Credit:Drew Carhart, Field Museum

The pebbles then entered a very slow orbit around the asteroid, and eventually, they fell back down to its surface further away where there was no deformation. Then, Heck and Yang say, the asteroid underwent another collision, the loose mixed pebbles on the surface got transformed into a solid rock. "It basically packed everything together, and this loose gravel became a cohesive rock," says Heck. The same impact may have dislodged the new rock, sending it careening into space. Eventually, that chunk fell to Earth as the Aguas Zarcas meteorite, carrying evidence of the pebble mixing.

This could explain the pebbles present in Aguas Zarcas, making the meteorite the first physical evidence of the geological process observed by OSIRIS-REx on Bennu. "It provides a new way of explaining the way that minerals on the surfaces of asteroids get mixed," says Yang.

That's a big deal, Heck says, because for a long time, scientists assumed that the main way that the minerals on the surfaces of asteroids get rearranged is through big crashes, which don't happen very often. "From OSIRIS-REx we know that these particle ejection events are much more frequent than these high-velocity impacts," says Heck, "so they probably play a more important role in determining the makeup of asteroids and meteorites."

Aguas Zarcas is the first meteorite to show signs of this behavior, but it's probably not the only one. "We would expect this in other meteorites," says Heck. "People just haven't looked for it yet." + Esplora ulteriormente