Credito:Shutterstock

Quando abbiamo collegato minuscoli dispositivi di localizzazione simili a uno zaino a cinque gazze australiane per uno studio pilota, non ci aspettavamo di scoprire un comportamento sociale completamente nuovo che raramente si vede negli uccelli.

Il nostro obiettivo era saperne di più sul movimento e le dinamiche sociali di questi uccelli altamente intelligenti e testare questi nuovi dispositivi durevoli e riutilizzabili. Invece, gli uccelli ci hanno superato in astuzia.

Come spiega il nostro nuovo documento di ricerca, le gazze hanno iniziato a mostrare prove di comportamenti cooperativi di "salvataggio" per aiutarsi a vicenda a rimuovere il localizzatore.

Anche se sappiamo che le gazze sono creature intelligenti e sociali, questa è stata la prima istanza di cui siamo a conoscenza che ha mostrato questo tipo di comportamento apparentemente altruistico:aiutare un altro membro del gruppo senza ottenere una ricompensa immediata e tangibile.

Test di nuovi fantastici dispositivi

Come scienziati accademici, siamo abituati agli esperimenti che vanno male in un modo o nell'altro. Sostanze scadute, apparecchiature difettose, campioni contaminati, un'interruzione di corrente non pianificata:tutto ciò può far tornare indietro di mesi (o addirittura anni) la ricerca attentamente pianificata.

Per quelli di noi che studiano gli animali, e in particolare il comportamento, l'imprevedibilità fa parte della descrizione del lavoro. Questo è il motivo per cui spesso richiediamo studi pilota.

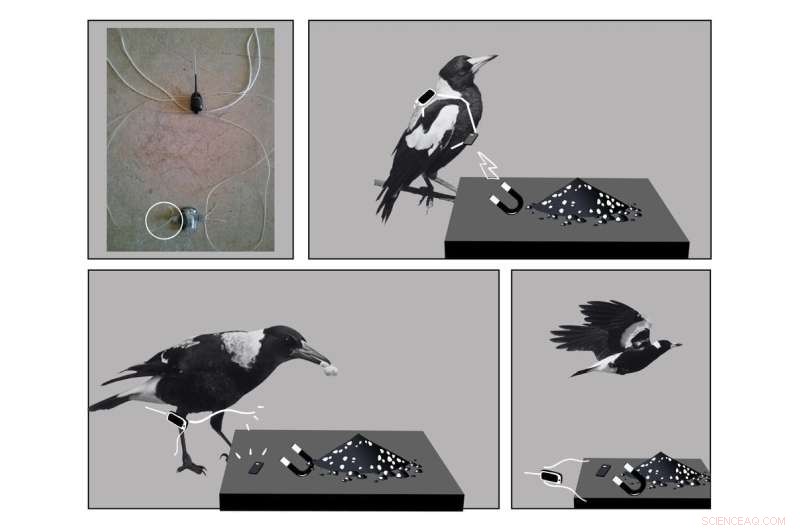

Uno dei tracker che abbiamo attaccato a cinque gazze, che pesa meno di un grammo. Credito:Dominique Potvin, autore fornito

Il nostro studio pilota è stato uno dei primi nel suo genere:la maggior parte dei tracker sono troppo grandi per adattarsi a uccelli di dimensioni medio-piccole e quelli che tendono ad avere una capacità molto limitata per l'archiviazione dei dati o la durata della batteria. Inoltre tendono ad essere monouso.

Un nuovo aspetto della nostra ricerca è stato il design dell'imbracatura che conteneva il tracker. Abbiamo ideato un metodo che non richiedesse di catturare nuovamente gli uccelli per scaricare dati preziosi o riutilizzare i piccoli dispositivi.

Abbiamo addestrato un gruppo di gazze locali a recarsi in una "stazione" di alimentazione a terra all'aperto che potrebbe caricare in modalità wireless la batteria del localizzatore, scaricare dati o rilasciare il localizzatore e l'imbracatura utilizzando un magnete.

L'imbracatura era resistente, con un solo punto debole in cui il magnete poteva funzionare. Per rimuovere l'imbracatura, era necessario quel magnete o delle ottime forbici. Siamo rimasti entusiasti del design, poiché ha aperto molte possibilità di efficienza e ha consentito la raccolta di molti dati.

We wanted to see if the new design would work as planned, and discover what kind of data we could gather. How far did magpies go? Did they have patterns or schedules throughout the day in terms of movement, and socialising? How did age, sex or dominance rank affect their activities?

All this could be uncovered using the tiny trackers—weighing less than one gram—we successfully fitted five of the magpies with. All we had to do was wait, and watch, and then lure the birds back to the station to gather the valuable data.

It was not to be

Many animals that live in societies cooperate with one another to ensure the health, safety and survival of the group. In fact, cognitive ability and social cooperation has been found to correlate. Animals living in larger groups tend to have an increased capacity for problem solving, such as hyenas, spotted wrasse, and house sparrows.

Australian magpies are no exception. As a generalist species that excels in problem solving, it has adapted well to the extreme changes to their habitat from humans.

Australian magpies generally live in social groups of between two and 12 individuals, cooperatively occupying and defending their territory through song choruses and aggressive behaviors (such as swooping). These birds also breed cooperatively, with older siblings helping to raise young.

During our pilot study, we found out how quickly magpies team up to solve a group problem. Within ten minutes of fitting the final tracker, we witnessed an adult female without a tracker working with her bill to try and remove the harness off of a younger bird.

Within hours, most of the other trackers had been removed. By day 3, even the dominant male of the group had its tracker successfully dismantled.

We don't know if it was the same individual helping each other or if they shared duties, but we had never read about any other bird cooperating in this way to remove tracking devices.

Our new tracker design was innovative, allowing a magnet to release the harness. Credit:Dominique Potvin, Author provided

The birds needed to problem solve, possibly testing at pulling and snipping at different sections of the harness with their bill. They also needed to willingly help other individuals, and accept help.

The only other similar example of this type of behavior we could find in the literature was that of Seychelles warblers helping release others in their social group from sticky Pisonia seed clusters. This is a very rare behavior termed "rescuing."

Saving magpies

So far, most bird species that have been tracked haven't necessarily been very social or considered to be cognitive problem solvers, such as waterfowl and raptors. We never considered the magpies may perceive the tracker as some kind of parasite that requires removal.

Tracking magpies is crucial for conservation efforts, as these birds are vulnerable to the increasing frequency and intensity of heatwaves under climate change.

In a study published this week, Perth researchers showed the survival rate of magpie chicks in heatwaves can be as low as 10%.

Importantly, they also found that higher temperatures resulted in lower cognitive performance for tasks such as foraging. This might mean cooperative behaviors become even more important in a continuously warming climate.

Just like magpies, we scientists are always learning to problem solve. Now we need to go back to the drawing board to find ways of collecting more vital behavioral data to help magpies survive in a changing world.