In questo lunedì, 10 dicembre 2018, foto, Robe, un diciottenne dipendente dalla tecnologia della California, lascia un fienile dopo aver aiutato a nutrire gli animali al Rise Up Ranch fuori Garofano rurale, Wash. Il ranch è un punto di partenza per clienti come Robel che vengono a reSTART Life, un programma residenziale per adolescenti e adulti che hanno seri problemi con un uso eccessivo di tecnologia, compresi i videogiochi. L'organizzazione, iniziata una decina di anni fa, inoltre sta aggiungendo servizi ambulatoriali a causa della forte domanda. (Foto AP/Martha Irvine)

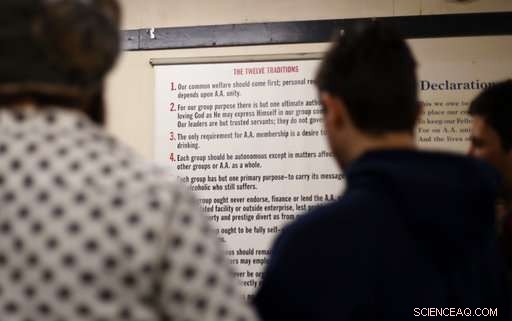

I giovani si siedono su sedie in cerchio in una piccola sala riunioni nella periferia di Seattle e si presentano prima di parlare. È molto simile a qualsiasi altro incontro in 12 fasi, ma con una svolta.

"Ciao, Il mio nome è, " ognuno inizia. Poi qualcosa come, "e sono un drogato di Internet e della tecnologia."

Gli otto che si sono riuniti qui sono assaliti da un livello di ossessione tecnologica che è diverso da quello di quelli di noi a cui piace dire che siamo dipendenti dai nostri telefoni o da un'app o da qualche nuovo spettacolo su un servizio di video in streaming. Per loro, la tecnologia ostacola il funzionamento quotidiano e la cura di sé. Stiamo parlando di bocciati, non riesco a trovare un lavoro, tipi di problemi che vivono in un buco nero, con la depressione, ansia e talvolta pensieri suicidi fanno parte del mix.

C'è Cristiano, uno studente universitario di 20 anni del Wyoming che ha un trauma cranico. Sua madre lo ha esortato a cercare aiuto perché stava "curando" la sua depressione con videogiochi e marijuana.

Seth, un 28enne del Minnesota, ha usato videogiochi e un sacco di cose per cercare di intorpidire la sua vergogna dopo che un'auto che stava guidando si è schiantata, ferendo gravemente il fratello.

Noi s, 21, un Eagle Scout e uno studente universitario del Michigan, giocava ai videogiochi 80 ore a settimana, fermandosi a mangiare solo ogni due o tre giorni. Ha perso 25 libbre e ha fallito le sue lezioni.

Dall'altra parte della città c'è un altro giovane che ha partecipato a questo incontro, prima che il suo programma di lavoro cambiasse, e il suo lavoro lo mette direttamente a rischio della tentazione.

Si occupa della manutenzione del cloud per un'azienda tecnologica suburbana di Seattle. Per un dipendente dalla tecnologia che si autodefinisce, è come lavorare nella fossa dei leoni, lavorando per la stessa industria che vende i giochi, video e altri contenuti online che a lungo sono stati il suo vizio.

In questo lunedì, 10 dicembre 2018, foto, Robe, un diciottenne dipendente dalla tecnologia della California, sinistra, aiuta Hilarie Cash a caricare il fieno per nutrire i cavalli al Rise Up Ranch fuori Garofano rurale, Wash. Il ranch è un punto di partenza per clienti come Robel che vengono a reSTART Life, un programma residenziale per adolescenti e adulti che hanno seri problemi con un uso eccessivo di tecnologia, compresi i videogiochi. L'organizzazione, iniziata una decina di anni fa, inoltre sta aggiungendo servizi ambulatoriali a causa della forte domanda. Cash è uno psicologo, direttore clinico e co-fondatore di reSTART. (Foto AP/Martha Irvine)

"Sono come un alcolizzato che lavora in un bar, "si lamenta il 27enne.

___

"Le droghe del passato sono ora riconfezionate. Abbiamo un nuovo nemico, " Cosette Rae dice della raffica di tecnologia. Un ex sviluppatore nel mondo della tecnologia, dirige un centro di riabilitazione dell'area di Seattle chiamato reSTART Life, uno dei pochi programmi residenziali della nazione specializzato nella dipendenza dalla tecnologia.

Uso di quella parola—dipendenza—quando si tratta di dispositivi, contenuti online e simili, è ancora dibattuto nel mondo della salute mentale. Ma molti professionisti concordano sul fatto che l'uso della tecnologia è sempre più intrecciato con i problemi di coloro che cercano aiuto.

Una revisione della ricerca mondiale dell'American Academy of Pediatrics ha rilevato che l'uso eccessivo dei soli videogiochi è un problema serio per ben il 9% dei giovani. Quest'estate, l'Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità ha anche aggiunto "disturbo da gioco" alla sua lista di afflizioni. Una diagnosi simile viene presa in considerazione negli Stati Uniti.

Può essere un argomento tabù in un settore che spesso affronta critiche per l'utilizzo di "design persuasivo, " Sfruttare intenzionalmente concetti psicologici per rendere la tecnologia ancora più allettante. Ecco perché il 27enne che lavora presso l'azienda tecnologica ha parlato a condizione che la sua identità non venga rivelata. Teme che parlare possa danneggiare la sua carriera nascente.

"Rimango nel settore tecnologico perché credo davvero che la tecnologia possa aiutare altre persone, "dice il giovane. Vuole fare del bene.

Ma mentre i suoi colleghi si stringono nelle vicinanze, parlando con entusiasmo dei loro ultimi exploit di videogiochi, si mette le cuffie, sperando di bloccare il frequente argomento di conversazione in questa parte del mondo incentrata sulla tecnologia.

In questo 9 dicembre, foto 2018, un tossicodipendente tecnologico di 27 anni posa per un ritratto di fronte a un negozio di videogiochi in un centro commerciale a Everett, Wash. Ha chiesto di rimanere anonimo perché lavora nel settore tecnologico e teme che parlare degli aspetti negativi dell'uso eccessivo di tecnologia possa danneggiare la sua carriera. "Se arriviamo a un punto nel settore tecnologico in cui posso usare il mio nome e mostrare la mia faccia in casi come questo, quindi sono arrivato da qualche parte. Sarà un punto di svolta." (AP Photo/Martha Irvine)

Anche lo schermo del computer di fronte a lui potrebbe portarlo fuori strada. Ma lui scava, digitando con determinazione sulla tastiera per concentrarsi nuovamente sul compito da svolgere.

___

I demoni non sono facili da combattere per questo giovane, nato nel 1991, lo stesso anno in cui il World Wide Web è diventato pubblico.

Da bambino, si sedette sulle ginocchia di suo padre mentre giocavano a semplici videogiochi su un computer Mac Classic II. Insieme nella loro casa nella zona di Seattle, hanno navigato in Internet su quello che allora era un nuovo servizio rivoluzionario chiamato Prodigy. Il suono del rimbalzo, quindi i toni acuti della connessione dial-up vengono incisi nella sua memoria.

Dalla prima scuola elementare, ottenne la sua prima console Super Nintendo e si innamorò di "Yoshi's Story, " un gioco in cui il protagonista cercava "frutto fortunato".

Man mano che cresceva, così ha fatto uno dei principali hub tecnologici del mondo. Guidato da Microsoft, è sorto dall'anonimo paesaggio suburbano e dai campi coltivati qui, a breve distanza dalla casa che condivide ancora con sua madre, che si è separata dal marito quando il loro unico figlio aveva 11 anni.

Il ragazzo sognava di far parte di questo boom tecnologico e, in terza media, scrisse una nota a se stesso. "Voglio essere un ingegnere informatico, " legge.

Molto brillante e con la testa piena di fatti e cifre, di solito andava bene a scuola. Si interessò anche alla musica e alla recitazione, ma ricorda come i giochi diventassero sempre più un modo per sfuggire alla vita:il dolore che provava, ad esempio, quando i suoi genitori hanno divorziato o quando la sua prima fidanzata seria gli ha spezzato il cuore all'età di 14 anni. Quella relazione è ancora la sua più lunga.

In questo lunedì, Dec. 10, 2018, foto, Psychologist Hilarie Cash walks on a forest path at a rehab center for adolescents in a rural area outside Redmond, Wash. The complex is part of reSTART Life, a residential program for adolescents and adults who have serious issues with excessive tech use, including video games. Disconnecting from tech and getting outside is part of the rehabilitation process. The organization, which began about a decade ago, also is adding outpatient services due to high demand. Cash is chief clinical officer and a co-founder at reSTART. (Foto AP/Martha Irvine)

"Hey, do you wanna go out?" friends would ask.

"No, man, I got plans. I can't do it this weekend. Scusate, " was his typical response, if he answered at all.

"And then I'd just go play video games, " he says of his adolescent "dark days, " exacerbated by attention deficit disorder, depression and major social anxiety.

Anche adesso, if he thinks he's said something stupid to someone, his words are replaced with a verbal tick - "Tsst, tsst"—as he replays the conversation in his head.

"There's always a catalyst and then it usually bubbles up these feelings of avoidance, " he says. "I go online instead of dealing with my feelings."

He'd been seeing a therapist since his parents' divorce. But attending college out of state allowed more freedom and less structure, so he spent even more time online. His grades plummeted, forcing him to change majors, from engineering to business.

Infine, he graduated in 2016 and moved home. Ogni giorno, he'd go to a nearby restaurant or the library to use the Wi-Fi, claiming he was looking for a job but having no luck.

Anziché, he was spending hours on Reddit, an online forum where people share news and comments, or viewing YouTube videos. Qualche volta, he watched online porn.

In questo 8 dicembre, foto 2018, young men gather to talk after a 12-step meeting for Internet &Tech Addiction Anonymous in Bellevue, Wash. The meeting is run much like other 12-step meetings for addicts, but the focus is video games, devices and internet content that has become a life-harming distraction. The Seattle area has become a hub for treatment of extreme tech use. (Foto AP/Martha Irvine)

Anche adesso, his mom doesn't know that he lied. "I still need to apologize for that, " lui dice, quietly.

___

The apologies will come later, in Step 9 of his 12-step program, which he found with the help of a therapist who specializes in tech addiction. He began attending meetings of the local group called Internet &Tech Addiction Anonymous in the fall of 2016 and landed his current job a couple months later.

For a while now, he's been stuck on Step 4—the personal inventory—a challenge to take a deep look at himself and the source of his problems. "It can be overwhelming, " lui dice.

The young men at the recent 12-step meeting understand the struggle.

"I had to be convinced that this was a 'thing, '" says Walker, a 19-year-old from Washington whose parents insisted he get help after video gaming trashed his first semester of college. He and others from the meeting agreed to speak only if identified by first name, as required by the 12-step tenets.

That's where facilities like reSTART come in. They share a group home after spending several weeks in therapy and "detoxing" at a secluded ranch. One recent early morning at the ranch outside Carnation, Washington, an 18-year-old from California named Robel was up early to feed horses, goats and a couple of farm cats—a much different routine than staying up late to play video games. He and other young men in the house also cook meals for one another and take on other chores.

Infine, they write "life balance plans, " committing to eating well and regular sleep and exercise. They find jobs and new ways to socialize, and many eventually return to college once they show they can maintain "sobriety" in the real world. They make "bottom line" promises to give up video games or any other problem content, as well as drugs and alcohol, if those are issues. They're also given monitored smartphones with limited function—calls, texts and emails and access to maps.

In questo lunedì, Dec. 10, 2018, foto, Jason, a 24-year-old tech addict from New York state, works on a laptop in Bellevue, Lavare., at the headquarters of reSTART Life, a residential program for adolescents and adults who have serious issues with excessive tech use, including video games. Jason came to reSTART several months ago because excessive use of video games had become a problem. "I knew I'd have to change or I'd end up killing myself, " said Jason, who is now living independently, has a job and is able to use some technology. He plans to start his first pre-med class, biologia, a gennaio. (Foto AP/Martha Irvine)

"It's more like an eating disorder because they have to learn to use tech, " just as anorexics need to eat, says Hilarie Cash, chief clinical officer and another co-founder at reSTART, which opened nearly a decade ago. They've since added an adolescent program and will soon offer outpatient services because of growing demand.

The young tech worker, who grew up just down the road, didn't have the funds to go to such a program—it's not covered by insurance, because tech addiction is not yet an official diagnosis.

But he, pure, has apps on his phone that send reports about what he's viewing to his 12-step sponsor, a fellow tech addict named Charlie, a 30-year-old reSTART graduate.

A casa, the young man also persuaded his mom to get rid of Wi-Fi to lessen the temptation. Mom struggles with her own addiction—over-eating—so she's tried to be as supportive as she can.

It hasn't been easy for her son, who still relapses every month or two with an extended online binge. He's managed to keep his job. But sometimes, he wishes he could be more like his co-workers, who spend a lot of their leisure time playing video games and seem to function just fine.

"Deep down, I think there's a longing to be one of those people, " Charlie says.

That's true, the young man concedes. He still has those days when he's tired, upset or extremely bored—and he tests the limits.

He tells himself he's not as bad as other addicts. Charlie knows something's up when his calls or texts aren't returned for several days, or even weeks.

In questo 8 dicembre, 2018, foto, young men gather to talk after a 12-step meeting for Internet &Tech Addiction Anonymous in Bellevue, Wash. The meeting is run much like other 12-step meetings for addicts, but the focus is video games, devices and internet content that has become a life-harming distraction. The Seattle area has become a hub for treatment of extreme tech use. (Foto AP/Martha Irvine)

"Quindi, " the young man says, "I discover very quickly that I am actually an addict, and I do need to do this."

Having Charlie to lean on helps. "He's a role model, " lui dice.

"He has a place of his own. He has a dog. He has friends."

That's what he wants for himself.

© 2018 The Associated Press. Tutti i diritti riservati.