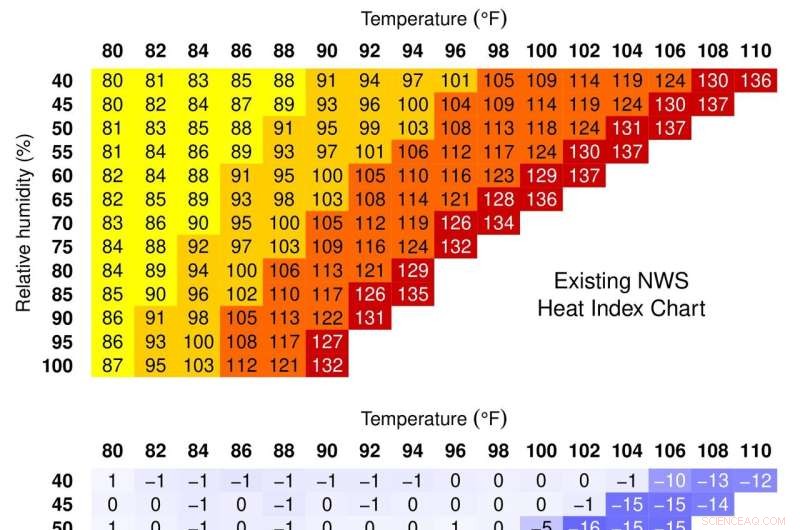

La tabella dell'indice di calore a lungo utilizzata (in alto) sottostima la temperatura apparente per le condizioni di calore e umidità più estreme che si verificano oggi (al centro). La versione corretta (in basso) è accurata per l'intera gamma di temperature e umidità che gli esseri umani incontreranno con il cambiamento climatico. Credito:David Romps e Yi-Chuan Lu, UC Berkeley

Se hai guardato l'indice di calore durante le ondate di caldo appiccicose di questa estate e hai pensato:"Sicuramente fa più caldo", potresti avere ragione.

Un'analisi degli scienziati del clima presso l'Università della California, a Berkeley, rileva che la temperatura apparente, o indice di calore, calcolato dai meteorologi e dal National Weather Service (NWS) per indicare quanto fa caldo, tenendo conto dell'umidità, sottostima la percezione temperatura per i giorni più torridi che stiamo vivendo, a volte di oltre 20 gradi Fahrenheit.

La scoperta ha implicazioni per coloro che soffrono queste ondate di calore, poiché l'indice di calore è una misura di come il corpo affronta il calore quando l'umidità è alta e la sudorazione diventa meno efficace nel raffreddarci. Sudorazione e vampate di calore, dove il sangue viene deviato verso i capillari vicini alla pelle per dissipare il calore, e lo spargimento di vestiti sono i modi principali con cui gli esseri umani si adattano alle temperature calde.

Un indice di calore più alto significa che il corpo umano è più stressato durante queste ondate di calore di quanto i funzionari della sanità pubblica possano realizzare, affermano i ricercatori. Il NWS attualmente considera un indice di calore superiore a 103 pericoloso e superiore a 125 estremamente pericoloso.

"Il più delle volte, l'indice di calore che il National Weather Service ti sta dando è il valore giusto. È solo in questi casi estremi che ottengono il numero sbagliato", ha affermato David Romps, professore di terra e planetario della UC Berkeley scienza. "Il punto in cui conta è quando inizi a mappare l'indice di calore sugli stati fisiologici e ti rendi conto, oh, queste persone sono stressate da una condizione di flusso sanguigno cutaneo molto elevato in cui il corpo sta per esaurire i trucchi per compensare per questo tipo di calore e umidità. Quindi, siamo più vicini a quel limite di quanto pensassimo di essere prima."

Romps e lo studente laureato Yi-Chuan Lu hanno dettagliato la loro analisi in un documento accettato dalla rivista Lettere di ricerca ambientale e pubblicato online il 12 agosto.

L'indice di calore è stato ideato nel 1979 da un fisico tessile, Robert Steadman, che ha creato semplici equazioni per calcolare quella che ha chiamato la relativa "afa" delle condizioni calde e umide, nonché calde e aride, durante l'estate. Lo vedeva come un complemento al fattore vento freddo comunemente usato in inverno per stimare quanto fa freddo.

Il suo modello ha preso in considerazione il modo in cui gli esseri umani regolano la loro temperatura interna per ottenere il comfort termico in diverse condizioni esterne di temperatura e umidità, modificando consapevolmente lo spessore degli indumenti o regolando inconsciamente la respirazione, la traspirazione e il flusso sanguigno dal nucleo del corpo alla pelle.

Nel suo modello, la temperatura apparente in condizioni ideali - una persona di taglia media all'ombra con acqua illimitata - è quanto si sentirebbe caldo se l'umidità relativa fosse a un livello confortevole, che Steadman riteneva essere una pressione di vapore di 1.600 pascal .

For example, at 70% relative humidity and 68 F—which is often taken as average humidity and temperature—a person would feel like it's 68 F. But at the same humidity and 86 F, it would feel like 94 F.

The heat index has since been adopted widely in the United States, including by the NWS, as a useful indicator of people's comfort. But Steadman left the index undefined for many conditions that are now becoming increasingly common. For example, for a relative humidity of 80%, the heat index is not defined for temperatures above 88 F or below 59 F. Today, temperatures routinely rise above 90 F for weeks at a time in some areas, including the Midwest and Southeast.

To account for these gaps in Steadman's chart, meteorologists extrapolated into these areas to get numbers, Romps said, that are correct most of the time, but not based on any understanding of human physiology.

"There's no scientific basis for these numbers," Romps said.

He and Lu set out to extend Steadman's work so that the heat index is accurate at all temperatures and all humidities between zero and 100%.

"The original table had a very short range of temperature and humidity and then a blank region where Steadman said the human model failed," Lu said. "Steadman had the right physics. Our aim was to extend it to all temperatures so that we have a more accurate formula."

One condition under which Steadman's model breaks down is when people perspire so much that sweat pools on the skin. At that point, his model incorrectly had the relative humidity at the skin surface exceeding 100%, which is physically impossible.

"It was at that point where this model seems to break, but it's just the model telling him, hey, let sweat drip off the skin. That's all it was," Romps said. "Just let the sweat drop off the skin."

That and a few other tweaks to Steadman's equations yielded an extended heat index that agrees with the old heat index 99.99% of the time, Romps said, but also accurately represents the apparent temperature for regimes outside those Steadman originally calculated. When he originally published his apparent temperature scale, he considered these regimes too rare to worry about, but high temperatures and humidities are becoming increasingly common because of climate change.

Romps and Lu had published the revised heat index equation earlier this year. In the most recent paper, they apply the extended heat index to the top 100 heat waves that occurred between 1984 and 2020. The researchers find mostly minor disagreements with what the NWS reported at the time, but also some extreme situations where the NWS heat index was way off.

One surprise was that seven of the 10 most physiologically stressful heat waves over that time period were in the Midwest—mostly in Illinois, Iowa and Missouri—not the Southeast, as meteorologists assumed. The largest discrepancies between the NWS heat index and the extended heat index were seen in a wide swath, from the Great Lakes south to Louisiana.

During the July 1995 heat wave in Chicago, for example, which killed at least 465 people, the maximum heat index reported by the NWS was 135 F, when it actually felt like 154 F. The revised heat index at Midway Airport, 141 F, implies that people in the shade would have experienced blood flow to the skin that was 170% above normal. The heat index reported at the time, 124 F, implied only a 90% increase in skin blood flow. At some places during the heat wave, the extended heat index implies that people would have experienced an increase of 820% above normal skin blood flow.

"I'm no physiologist, but a lot of things happen to the body when it gets really hot," Romps said. "Diverting blood to the skin stresses the system because you're pulling blood that would otherwise be sent to internal organs and sending it to the skin to try to bring up the skin's temperature. The approximate calculation used by the NWS, and widely adopted, inadvertently downplays the health risks of severe heat waves."

Physiologically, the body starts going haywire when the skin temperature rises to equal the body's core temperature, typically taken as 98.6 F. After that, the core temperature begins to increase. The maximum sustainable core temperature is thought to be 107 F—the threshold for heat death. For the healthiest of individuals, that threshold is reached at a heat index of 200 F.

Luckily, humidity tends to decrease as temperature increases, so Earth is unlikely to reach those conditions in the next few decades. Less extreme—though still deadly—conditions are nevertheless becoming common around the globe.

"A 200 F heat index is an upper bound of what is survivable," Romps said. "But now that we've got this model of human thermoregulation that works out at these conditions, what does it actually mean for the future habitability of the United States and the planet as a whole? There are some frightening things we are looking at." + Esplora ulteriormente