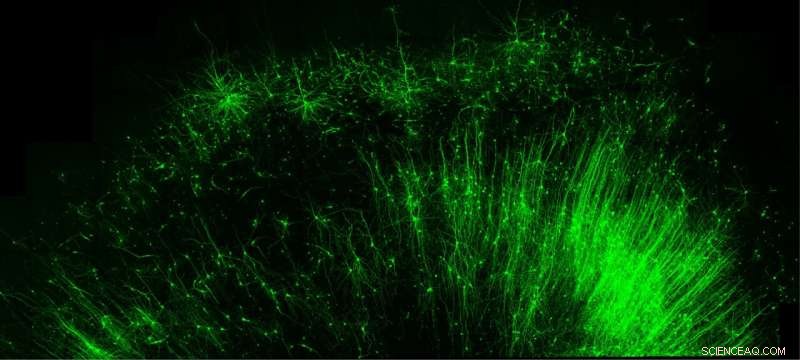

Contrassegnare e illuminare solo le cellule "freno" inibitorie (verdi) nel tessuto cerebrale umano è solo una delle tante cose che il nuovo strumento della Duke University, CellREADR, può fare. Credito:Derek Southwell, Duke University

I ricercatori della Duke University hanno sviluppato uno strumento di editing basato sull'RNA che prende di mira le singole cellule, piuttosto che i geni. È in grado di prendere di mira con precisione qualsiasi tipo di cellula e di aggiungere selettivamente qualsiasi proteina di interesse.

I ricercatori hanno affermato che lo strumento potrebbe consentire di modificare cellule e funzioni cellulari molto specifiche per gestire la malattia.

Utilizzando una sonda a base di RNA, un team guidato dal neurobiologo Z. Josh Huang, Ph.D. e ricercatore post-dottorato Yongjun Qian, Ph.D. hanno dimostrato che possono introdurre nelle cellule etichette fluorescenti per etichettare tipi specifici di tessuto cerebrale; un interruttore on/off sensibile alla luce per silenziare o attivare neuroni di loro scelta; e persino un enzima autodistruggente per espellere con precisione alcune cellule ma non altre. L'opera appare il 5 ottobre su Nature .

Il loro sistema di monitoraggio e controllo cellulare selettivo si basa sull'enzima ADAR, che si trova nelle cellule di ogni animale. Sebbene questi siano i primi giorni per CellREADR (Cell access through RNA sensing by Endogenous ADAR), le possibili applicazioni sembrano essere infinite, ha affermato Huang, così come il suo potenziale per funzionare in tutto il regno animale.

"Siamo entusiasti perché questo fornisce una tecnologia semplificata, scalabile e generalizzabile per monitorare e manipolare tutti i tipi di cellule in qualsiasi animale", ha detto Huang. "Potremmo effettivamente modificare tipi specifici di funzione cellulare per gestire le malattie, indipendentemente dalla loro predisposizione genetica iniziale", ha affermato. "Non è possibile con le attuali terapie o medicine."

CellREADR è una stringa personalizzabile di RNA composta da tre sezioni principali:un sensore, un segnale di stop e una serie di progetti.

In primo luogo, il team di ricerca decide quale tipo di cellula specifico vuole studiare e identifica un RNA bersaglio che è prodotto in modo univoco da quel tipo di cellula. La notevole specificità tissutale dello strumento si basa sul fatto che ogni tipo di cellula produce un RNA caratteristico che non si vede in altri tipi di cellule.

Una sequenza di sensori viene quindi progettata come filamento complementare dell'RNA bersaglio. Proprio come i gradini del DNA sono costituiti da molecole complementari che sono intrinsecamente attratte l'una dall'altra, l'RNA ha lo stesso potenziale magnetico per legarsi con un altro pezzo di RNA se ha molecole corrispondenti.

Dopo che un sensore si è fatto strada in una cellula e ha trovato la sua sequenza di RNA bersaglio, entrambi i pezzi si uniscono per creare un pezzo di RNA a doppio filamento. Questo nuovo mashup di RNA attiva l'enzima ADAR per ispezionare la nuova creazione e quindi modificare un singolo nucleotide del suo codice.

The ADAR enzyme is a cell-defense mechanism designed to edit double-strand RNA when it occurs, and is believed to be found in all animal cells.

Knowing this, Qian designed CellREADR's stop sign using the same specific nucleotide ADAR edits in double-stranded RNA. The stop sign, which prevents the protein blueprints from being built, is only removed once CellREADR's sensor docks to its target RNA sequence, making it highly specific for a given cell type.

Once ADAR removes the stop sign, the blueprints can be read by cellular machinery that builds the new protein inside the target cell.

In their paper, Huang and his team put CellREADR through its paces. "I remember two years ago when Yongjun built the first iteration of CellREADR and tested it in a mouse brain," Huang said. "To my amazement, it worked spectacularly on his first try."

The team's careful planning and design paid off as they were then able to demonstrate CellREADR accurately labelled specific brain cell populations in living mice, as well as effectively added activity monitors and control switches where directed. It also worked well in rats, and in human brain tissue collected from epilepsy surgeries.

"With CellREADR, we can pick and choose populations to study and really begin to investigate the full range of cell types present in the human brain," said co-author Derek Southwell, M.D., Ph.D., a neurosurgeon and assistant professor in the department of neurosurgery at Duke.

Southwell hopes CellREADR will improve his and others' understanding of the wiring diagram for human brain circuits and the cells within them, and in doing so, help advance new therapies for neurological disorders, such as a promising new method to treat drug-resistant epilepsy he is piloting.

Huang and Qian are especially hopeful about CellREADR's potential as a "programmable RNA medicine" to possibly cure diseases—since that's what drew them both to science in the first place. They have applied for a patent on the technology.

"When I majored in pharmacology as an undergraduate, I was very naïve," Qian said. "I thought you could do a lot of things, like cure cancer, but actually it's very difficult. However, now I think, yes maybe we can do it." + Esplora ulteriormente