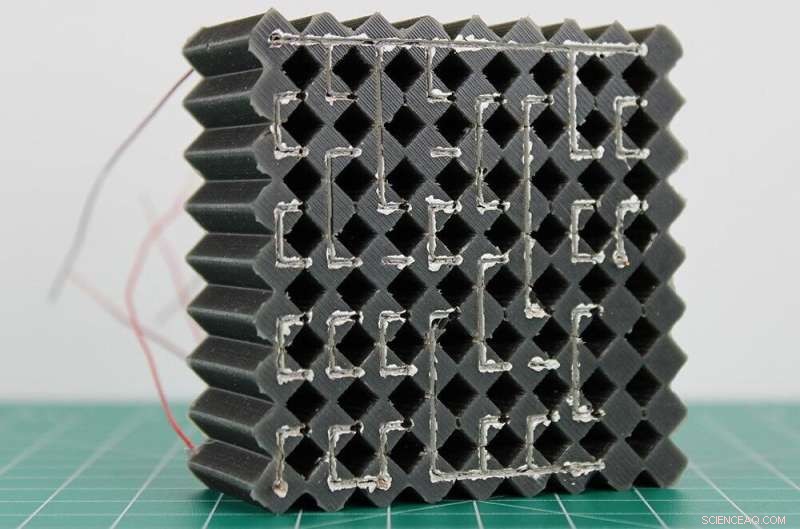

Un materiale per circuiti integrati meccanici può eseguire attività di calcolo come un computer senza bisogno del computer. Qui, il materiale di esempio esegue operazioni aritmetiche, confronta i numeri e converte le informazioni digitali in un display a LED. Credito:Charles El Helou/Penn State

Qualcuno ti tocca la spalla. I recettori tattili organizzati nella tua pelle inviano un messaggio al tuo cervello, che elabora le informazioni e ti indirizza a guardare a sinistra, nella direzione del tocco. Ora, i ricercatori della Penn State e della US Air Force hanno sfruttato questa elaborazione di informazioni meccaniche e l'hanno integrata in materiali ingegnerizzati che "pensano".

L'opera, pubblicata oggi su Natura , si basa su una nuova alternativa riconfigurabile ai circuiti integrati. I circuiti integrati sono in genere composti da più componenti elettronici alloggiati su un unico materiale semiconduttore, solitamente silicio, e gestiscono tutti i tipi di elettronica moderna, inclusi telefoni, automobili e robot. I circuiti integrati sono la realizzazione da parte degli scienziati dell'elaborazione delle informazioni simile al ruolo del cervello nel corpo umano. Secondo il ricercatore principale Ryan Harne, James F. Will Career Development Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering presso Penn State, i circuiti integrati sono il costituente fondamentale necessario per il calcolo scalabile di segnali e informazioni, ma non sono mai stati realizzati dagli scienziati in una composizione diversa dal silicio semiconduttori.

La scoperta del suo team ha rivelato l'opportunità per quasi tutto il materiale intorno a noi di agire come un proprio circuito integrato:essere in grado di "pensare" a ciò che sta accadendo intorno ad esso.

"Abbiamo creato il primo esempio di un materiale ingegneristico in grado di percepire, pensare e agire simultaneamente su sollecitazioni meccaniche senza richiedere circuiti aggiuntivi per elaborare tali segnali", ha affermato Harne. "Il materiale polimerico morbido agisce come un cervello in grado di ricevere stringhe digitali di informazioni che vengono quindi elaborate, dando luogo a nuove sequenze di informazioni digitali in grado di controllare le reazioni".

Il materiale meccanico morbido e conduttivo contiene circuiti riconfigurabili in grado di realizzare logiche combinatorie:quando il materiale riceve stimoli esterni, traduce l'input in informazioni elettriche che vengono poi elaborate per creare segnali in uscita. Il materiale potrebbe utilizzare la forza meccanica per calcolare aritmetica complessa, come hanno dimostrato Harne e il suo team, o rilevare frequenze radio per comunicare segnali luminosi specifici, tra gli altri potenziali esempi di traduzione. Le possibilità sono vaste, ha detto Harne, perché i circuiti integrati possono essere programmati per fare così tanto.

"Abbiamo scoperto come utilizzare la matematica e la cinematica, come si muovono i singoli componenti di un sistema, nelle reti meccanico-elettriche", ha detto Harne. "Questo ci ha permesso di realizzare una forma fondamentale di intelligenza nei materiali ingegneristici, facilitando l'elaborazione delle informazioni completamente scalabile intrinseca al sistema dei materiali morbidi."

I materiali dei circuiti integrati meccanici realizzati con materiali in gomma conduttivi e non conduttivi rilevano e reagiscono al modo in cui le forze vengono applicate ad essi. Credito:Charles El Helou/Penn State

According to Harne, the material uses a similar "thinking" process as humans and has potential applications in autonomous search-and-rescue systems, in infrastructure repairs and even in bio-hybrid materials that can identify, isolate and neutralize airborne pathogens.

"What makes humans smart is our means to observe and think about information we receive through our senses, reflecting on the relationship between that information and how we can react," Harne said.

While our reactions may seem automatic, the process requires nerves in the body to digitize the sensory information so that electrical signals can travel to the brain. The brain receives this informational sequence, assesses it and tells the body to react accordingly.

For materials to process and think about information in a similar way, they must perform the same intricate internal calculations, Harne said. When the researchers subject their engineered material to mechanical information—applied force that deforms the material—it digitizes the information to signals that its electrical network can advance and assess.

The process builds on the team's previous work developing a soft, mechanical metamaterial that could "think" about how forces are applied to it and respond via programmed reactions, detailed in Nature Communications last year. This earlier material was limited to only logic gates operating on binary input-output signals, according to Harne, and had no way to compute high-level logical operations that are central to integrated circuits.

The researchers were stuck, until they rediscovered a 1938 paper published by Claude E. Shannon, who later became known as the "father of information theory." Shannon described a way to create an integrated circuit by constructing mechanical-electrical switching networks that follow the laws of Boolean mathematics—the same binary logic gates Harne used previously.

"Ultimately, the semi-conductor industry did not adopt this method of making integrated circuits in the 1960s, opting instead to use a direct-assembly approach," Harne said. "Shannon's mathematically grounded design philosophy was lost to the sands of time, so, when we read the paper, we were astounded that our preliminary work exactly realized Shannon's vision."

However, Shannon's work was hypothetical, produced nearly 30 years before integrated circuits were developed, and did not address how to scale the networks.

"We made considerable modifications to Shannon's design philosophy in order for our mechanical-electrical networks to comply to the reality of integrated circuit assembly rules," Harne said. "We leapt off our core logic gate design philosophy from the 2021 research and fully synchronized the design principles to those articulated by Shannon to ultimately yield mechanical integrated circuit materials—the effective brain of artificial matter."

The researchers are now evolving the material to process visual information like it does physical signals.

"We are currently translating this to a means of 'seeing' to augment the sense of 'touching' we have presently created," Harne said. "Our goal is to develop a material that demonstrates autonomous navigation through an environment by seeing signs, following them and maneuvering out of the way of adverse mechanical force, such as something stepping on it."

Other authors of the paper include Charles El Helou, doctoral student in mechanical engineering at Penn State, and Benjamin Grossman, Christopher E. Tabor and Philip R. Buskohl from the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory. + Esplora ulteriormente