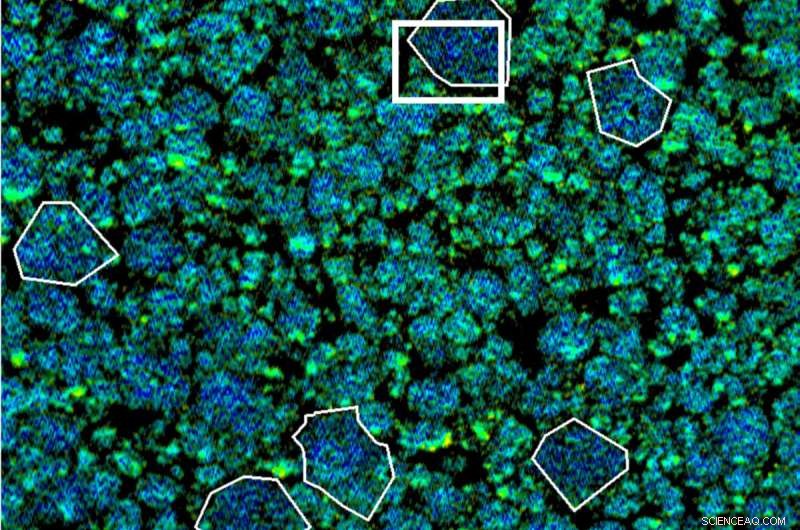

Le misurazioni dettagliate dei raggi X presso l'Advanced Light Source hanno aiutato un team di ricerca co-guidato da Berkeley Lab, SLAC e Stanford University a rivelare come l'ossigeno filtra dai miliardi di nanoparticelle che compongono gli elettrodi delle batterie agli ioni di litio. Credito:Berkeley Lab

In un periodo di tre mesi, l'auto media negli Stati Uniti produce una tonnellata di anidride carbonica. Moltiplicalo per tutte le auto a benzina sulla Terra, e che aspetto ha? Un problema insormontabile.

Ma i nuovi sforzi di ricerca dicono che c'è speranza se ci impegniamo a zero emissioni nette di carbonio entro il 2050 e sostituiamo i veicoli che consumano gas con veicoli elettrici, tra molte altre soluzioni di energia pulita.

Per aiutare la nostra nazione a raggiungere questo obiettivo, scienziati come William Chueh e David Shapiro stanno lavorando insieme per elaborare nuove strategie per progettare batterie più sicure a lunga distanza realizzate con materiali sostenibili e abbondanti per la Terra.

Chueh è professore associato di scienza dei materiali e ingegneria presso la Stanford University con l'obiettivo di riprogettare la moderna batteria dal basso verso l'alto. Si affida a strumenti all'avanguardia presso le strutture degli utenti scientifici del Dipartimento dell'Energia degli Stati Uniti come Advanced Light Source (ALS) di Berkeley Lab e Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light Source di SLAC, strutture di sincrotrone che generano fasci luminosi di raggi X, per svelare la dinamica molecolare dei materiali delle batterie al lavoro.

Per quasi un decennio, Chueh ha collaborato con Shapiro, uno scienziato senior presso l'ALS e uno dei principali esperti di sincrotrone, e insieme, il loro lavoro ha portato a nuove straordinarie tecniche che rivelano per la prima volta come funzionano i materiali delle batterie in azione, in tempo reale , a scale senza precedenti invisibili ad occhio nudo.

Discutono del loro lavoro pionieristico in questa sessione di domande e risposte.

D:Cosa ti ha interessato alla ricerca sulla batteria/l'accumulo di energia?

Chueh:Il mio lavoro è quasi interamente guidato dalla sostenibilità. Sono stato coinvolto nella ricerca sui materiali energetici quando ero uno studente laureato nei primi anni 2000, stavo lavorando sulla tecnologia delle celle a combustibile. Quando sono entrato a far parte di Stanford nel 2012, mi è apparso ovvio che l'accumulo di energia scalabile ed efficiente è fondamentale.

Oggi sono molto entusiasta di vedere che la transizione energetica lontano dai combustibili fossili sta diventando una realtà e che viene implementata su scala incredibile.

Ho tre obiettivi:in primo luogo, sto facendo una ricerca fondamentale che getti le basi per consentire la transizione energetica, soprattutto in termini di sviluppo dei materiali. In secondo luogo, sto formando scienziati e ingegneri di livello mondiale che usciranno nel mondo reale per risolvere questi problemi. E poi, terzo, prendo la scienza fondamentale e la traduco in un uso pratico attraverso l'imprenditorialità e il trasferimento tecnologico.

Quindi spero che questo ti dia una visione completa di ciò che mi guida e di ciò che penso serva per fare la differenza:sono la conoscenza, le persone e la tecnologia.

Shapiro:Il mio background è nell'ottica e nella diffusione coerente dei raggi X, quindi quando ho iniziato a lavorare all'ALS nel 2012, le batterie non erano davvero sul mio radar. Mi è stato assegnato il compito di sviluppare nuove tecnologie per la microscopia a raggi X ad alta risoluzione spaziale, ma questo ha portato rapidamente alle applicazioni e al tentativo di capire cosa stanno facendo i ricercatori del Berkeley Lab e oltre e quali sono le loro esigenze.

All'epoca, intorno al 2013, c'era molto lavoro all'ALS utilizzando varie tecniche che sfruttavano la sensibilità chimica dei raggi X morbidi per studiare le trasformazioni di fase nei materiali delle batterie, in particolare il litio ferro fosfato (LiFePO4) tra gli altri.

Sono rimasto davvero colpito dal lavoro di Will così come da Wanli Yang, Jordi Cabana (un ex scienziato del personale dell'Energy Technologies Area (ETA) del Berkeley Lab che ora è professore associato presso l'Università dell'Illinois a Chicago) e altri il cui lavoro ha anche costruito off of work by ETA researchers Robert Kostecki and Marca Doeff.

I knew nothing about batteries at the time, but the scientific and social impact of this area of research quickly became apparent to me. The synergy of research across Berkeley Lab also struck me as very profound, and I wanted to figure out how to contribute to that. So I started to reach out to people to see what we could do together.

As it turned out, there was a great need to improve the spatial resolution of our battery materials measurements and to look at them during cycling—and Will and I have been working on that for nearly a decade now.

Q:Will, as a battery scientist, what would you say is the biggest challenge to making better batteries?

Chueh:Batteries have on the order of 10 metrics that you have to co-optimize at the same time. It's easy to make a battery that's good on maybe five out of the 10, but to make a battery that's good in every metric is very immensely challenging.

For example, let's say you want a battery that is energy dense so you can drive an electric car for 500 miles per charge. You may want a battery that charges in 10 minutes. And you may want a battery that lasts 20 years. You also want a battery that never explodes. But it's hard to meet all of these metrics at once.

What we're trying to do is understand how we can create a single battery technology that is safe, long-lasting, and can be charged in 10 minutes.

And those are the fundamental insights that our experiments at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source are trying to do:To uncover those unexplained tradeoffs so that we can go beyond today's design rules, which would enable us to identify new materials and new mechanisms so that we can free ourselves from those restrictions.

Q:What unique capabilities does the ALS offer that have helped to push the boundaries of battery or energy storage research?

Chueh:In order to understand what's going on, we need to see it. We need to make observations. A key philosophy of my group is to embrace the dynamics and the heterogeneity of battery materials. A battery material is not like a rock. It's not static. You are charging and discharging it every day for your phones and every week for your electric cars. You're not going to understand how a car works by not driving it.

The second part is that heterogeneous battery materials are extremely length spanning. A battery cell is typically a few centimeters tall, but in order to understand what's going on inside the battery—and I have beautiful images for this—you want to see all the way down to the nanoscale and to the atomic scale. That's about 10 orders of magnitude of length.

What the Advanced Light Source empowers scientists like me to be able to do is to embrace the heterogeneity and dynamics of a battery in very unprecedented ways:We can measure very slow processes. We can measure very fast processes. We can measure things at the scale of many hundreds of microns (millionths of a meter). We can measure things at the nanoscale (billionth of a meter). All with one amazing tool at Berkeley Lab.

Shapiro:Scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) is a very popular synchrotron-based method. Most synchrotrons around the world have at least one STXM instrument while the ALS has three—and a fourth is on the way through the ALS Upgrade (ALS-U) project.

I think a few things make our program unique. First, we have a portfolio of instruments with specializations. One is optimized for light element spectroscopy so an element like oxygen, which is a critical ingredient in battery chemistry, can be precisely characterized.

Another instrument specializes in mapping chemical composition at very high spatial resolution. We have the highest spatial resolution X-ray microscopy in the world. This is very powerful for zooming in on the chemical reactions happening within a battery's individual nanoparticles and interfaces.

Our third instrument specializes in "operando" measurements of battery chemistry, which you need in order to really understand the physical and chemical evolution that occurs during battery cycling.

We have also worked hard to develop synergies with other facilities at Berkeley Lab. For instance, our high-resolution microscope uses the same sample environments as the electron microscopes at the Molecular Foundry, Berkeley Lab's nanoscience user facility—so it has become feasible to probe the same active battery environment with both X-rays and electrons. Will has used this correlative approach to study relationships between chemical states and structural strain in battery materials. This has never been done before at the length scales we have access to, and it provides new insight.

Q:How will the ALS Upgrade project advance next-gen energy storage technologies? What will the upgraded ALS offer battery/energy-storage researchers that will be unique to Berkeley Lab?

Shapiro:The upgraded ALS will be unique for a few reasons as far as microscopy is concerned. First, it will be the brightest soft X-ray source in the world, providing 100 times more X-rays on th sample than what we have today. Scanning microscopy techniques will benefit from such high brightness.

This is both a huge opportunity and a huge challenge. We can use this brightness to measure the data we get today—but doing this 100 times faster is the challenging part.

Such new capabilities will give us a much more statistically accurate look at battery structure and function by expanding to larger length scales and smaller time scales. Alternatively, we could also measure data at the same rate as today but with about three times finer spatial resolution, taking us from about 10 nanometers to just a few nanometers. This is a very important length scale for materials science, but today it's just not accessible by X-ray microscopy.

Another thing that will make the upgraded ALS unique is its proximity to expertise at the Molecular Foundry; other science areas such as the Energy Technologies Area; and current and future energy research hubs based at Berkeley Lab. This synergy will continue to drive energy storage research.

Chueh:In battery research, one of the challenges we have right now is that we have so many interesting problems to solve, but it takes hours and days to do just one measurement. The ALS-U project will increase the throughput of experiments and allow us to probe materials at higher resolution and smaller scales. Altogether, that adds up to enabling new science. Years ago, I contributed to making the case for ALS-U, so I couldn't be prouder to be part of that—I'm very excited to see the upgraded ALS come online so we can take advantage of its exciting new capabilities to do science that we cannot do today.