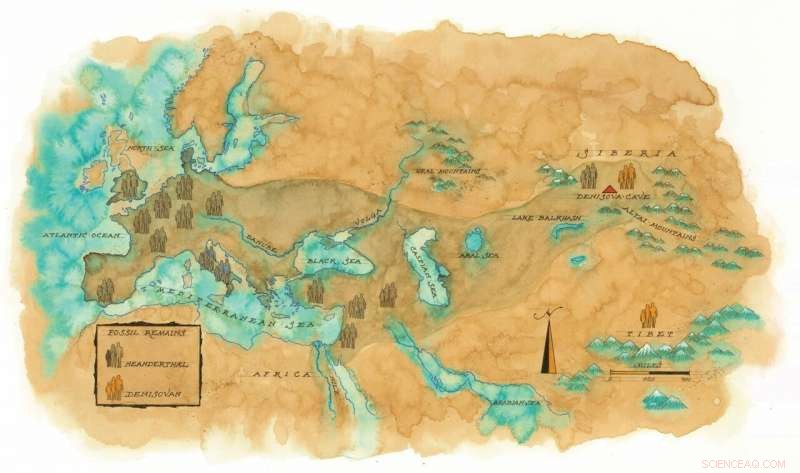

Joshua Akey, un professore del Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, utilizza un metodo di ricerca che chiama archeologia genetica per trasformare il modo in cui stiamo imparando a conoscere il nostro passato. Le prove fossili illustrano la diffusione di due specie di ominidi estinte da tempo, Neanderthal e Denisova. Gli esseri umani moderni portano i geni di queste specie, indicando che i nostri antenati diretti incontrarono e si accoppiarono con umani arcaici. Credito:Michael Francis Reagan

Per la maggior parte della nostra storia evolutiva, per la maggior parte del tempo che gli umani anatomicamente moderni sono stati sulla Terra, abbiamo condiviso il pianeta con altre specie di umani. È stato solo negli ultimi 30, 000 anni, il semplice battito di un occhio evolutivo, che gli umani moderni hanno occupato il pianeta come unico rappresentante del lignaggio degli ominidi.

Ma portiamo con noi prove di queste altre specie. In agguato all'interno del nostro genoma ci sono tracce di materiale genetico di una varietà di antichi umani che non esistono più. Queste tracce rivelano una lunga storia di mescolanze, come i nostri diretti antenati incontrarono e si accoppiarono con umani arcaici. Poiché utilizziamo tecnologie sempre più complesse per studiare queste connessioni genetiche, stiamo imparando non solo su questi esseri umani estinti, ma anche sul quadro più ampio di come ci siamo evoluti come specie.

Joshua Akey, un professore del Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, sta guidando gli sforzi per comprendere questo quadro più ampio. Chiama il suo metodo di ricerca archeologia genetica, e sta trasformando il modo in cui impariamo a conoscere il nostro passato. "Possiamo scavare diversi tipi di esseri umani non dalla sporcizia e dai fossili ma direttamente dal DNA, " Egli ha detto.

Combinando la sua esperienza in biologia ed evoluzione darwiniana con metodi computazionali e statistici, Akey studia le connessioni genetiche tra gli esseri umani moderni e due specie di ominidi estinti:Neanderthal, i classici "uomini delle caverne" della paleoantropologia; e Denisova, un umano arcaico scoperto di recente. La ricerca di Akey divulga una complessa storia della mescolanza dei primi esseri umani, indicativo di diversi millenni di movimenti di popolazione in tutto il mondo.

"C'è spesso un divario tra i ricercatori che escono e raccolgono campioni esotici e i ricercatori che fanno teoria e analisi dei dati davvero creative, e ha fatto entrambe le cose, " disse Kelley Harris, un ex collega di Akey che ora è assistente professore di scienze del genoma all'Università di Washington.

Come molti di noi, Akey è stato a lungo interessato a come si è evoluta la specie umana. "Le persone vogliono conoscere il loro passato, " disse. "Ma ancora di più, vogliamo sapere cosa significa essere umani".

Questa curiosità ha seguito Akey durante tutta la sua scuola. Durante il suo lavoro di laurea presso l'Università del Texas Health Science Center a Houston alla fine degli anni '90, ha osservato come gli esseri umani contemporanei in diverse parti del mondo fossero geneticamente imparentati l'uno con l'altro, e ha utilizzato metodi di sequenziamento genico precoci per cercare di comprendere queste relazioni.

I sequenziatori genici sono dispositivi che determinano l'ordine delle quattro basi chimiche (A, T, C e G) che costituiscono la molecola di DNA. Determinando l'ordine di queste basi, gli analisti possono identificare le informazioni genetiche codificate in un filamento di DNA.

Dagli anni '90, però, la tecnologia di sequenziamento genico è progredita notevolmente. Una nuova tecnologia nota come sequenziamento di nuova generazione è entrata in uso intorno al 2010 e ha permesso ai ricercatori di studiare un numero molto elevato di sequenze genetiche nel genoma umano. Ci sono voluti 10 anni per sequenziare il primo genoma umano, ma queste nuove macchine ottengono dati sull'intera sequenza del genoma da migliaia di individui in poche ore. "Quando la tecnologia di sequenziamento di nuova generazione ha iniziato a diventare la forza dominante nella genetica, "Akey ha detto, "questo ha cambiato completamente l'intero campo. È difficile sopravvalutare quanto sia stata drammatica questa tecnologia".

La scala dei dati che ora possono essere analizzati ha permesso ai ricercatori di affrontare tutta una serie di nuove domande che non sarebbero state possibili con la tecnologia precedente.

Joshua Akey e il suo team utilizzano tecnologie di sequenziamento genetico per rivelare nuove informazioni sui lignaggi umani arcaici e sulla nostra storia evolutiva. Credito:Sameer A. Khan/Fotobuddy

One of these questions is the relationship between modern humans and archaic humans, such as Neanderthals. Infatti, this question fostered a vigorous debate about whether modern humans carried genes from Neanderthals. Per molti anni, the opinions of researchers—both pro and con—ticked back and forth like a metronome.

Gradualmente, però, a few researchers—including geneticists Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute in Germany and his colleague Richard (Ed) Green of the University of California-Santa Cruz—began to demonstrate strong evidence that, infatti, there had been gene flow from Neanderthals to modern humans. In a 2010 paper, these researchers estimated that people of non-African ancestry had about 2% Neanderthal ancestry.

Neanderthals lived in a wide geographical swath across Europe, the Near East and Central Asia before dying out around 30, 000 anni fa. They lived alongside anatomically modern humans, who evolved in Africa some 200, 000 anni fa. The archaeological record shows that Neanderthals were adept at making stone tools and developed a number of physical traits that uniquely adapted them to cold, dark climates, such as broad noses, thick body hair and large eyes.

Following on the heels of Pääbo and Green's Neanderthal research, Akey and a colleague, Benjamin Vernot, published a paper in Science looking at recovering Neanderthal sequences from the genome of modern humans. Geneticist David Reich of Harvard University published a similar paper in Nature, e, insieme, the two papers provided the first data employing the modern genome to investigate our link with Neanderthals.

Using the genetic variation in contemporary populations to learn about things that happened in the past involves scrutinizing the modern human genome for gene sequences that display traits expected to have been inherited from a different type of human. Akey and his colleagues then take those sequences and compare them to the Neanderthal genome, looking for a match.

Using this technique, Akey has been able to uncover a rich human legacy of genetic interconnections on a scale previously unconceived. As stated, while the available evidence suggests that non-Africans carry about 2% of Neanderthal genes, Africans, who were once believed not to have any connections with Neanderthals, actually have approximately 0.5% Neanderthal genes. Researchers have further discovered that the Neanderthal genome has contributed to several diseases seen in modern human populations, come il diabete, arthritis and celiac disease. By the same token, some genes inherited from Neanderthals have proven beneficial or neutral, such as genes for hair and skin color, sleep patterns and even mood.

Akey has also discovered genetic fingerprints that suggest our human ancestry contains species about which we know nothing or very little. The Denisovans are a case in point. An archaic form of human, they coexisted with anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals and interbred with both before going extinct. The first evidence of their existence came in 2008 when a finger bone was discovered in Denisova Cave in the remote Altai Mountains of southern Siberia. At first the bone was assumed to be Neanderthal because the cave contained evidence of these species. Di conseguenza, it sat in a museum drawer in Leipzig, Germania, for many years before it was analyzed. But when it was, the researchers were dumbfounded. It wasn't a Neanderthal—it was a hitherto unknown type of ancient human. "The Denisovans are the first species ever identified directly from their DNA and not from fossil data, " Akey said.

Da quel tempo, continued genetic work—much of it conducted by Akey and his colleagues—has established that the closest living relatives of Denisovans are modern Melanesians, the inhabitants of the Melanesian islands of the western Pacific—places such as New Guinea, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and Fiji. These populations carry between 4% and 6% of Denisovan genes, though they also carry Neanderthal genes.

Examples like this highlight one of the main features of our human lineage, Akey said, that admixture has been a defining feature of our history. "Throughout human history there's always been admixture, " Akey said. "Populations split and they come back together."

While there remains a lot of debate about the Denisovans, Akey believes they most likely were closely related to Neanderthals, perhaps an eastern version who split off from the latter sometime around 300, 000 or 400, 000 anni fa. Recentemente, genetic analysis of fossils from Denisova Cave has uncovered evidence of an offspring between a Neanderthal woman and a Denisovan male. The offspring was a female who lived approximately 90, 000 anni fa. By looking at this genetic trail, Akey and other researchers have been able to piece together a fascinating story of human evolution—one that is promising to rewrite our understanding of early human origins.

But there's so much more to discover, Akey said. "Even though we have sequenced probably 100, 000 genomes already, and we have pretty sophisticated tools for looking at that variation, the more we think about how to interpret genetic variation, the more we find these hidden stories in our DNA, " Egli ha detto.