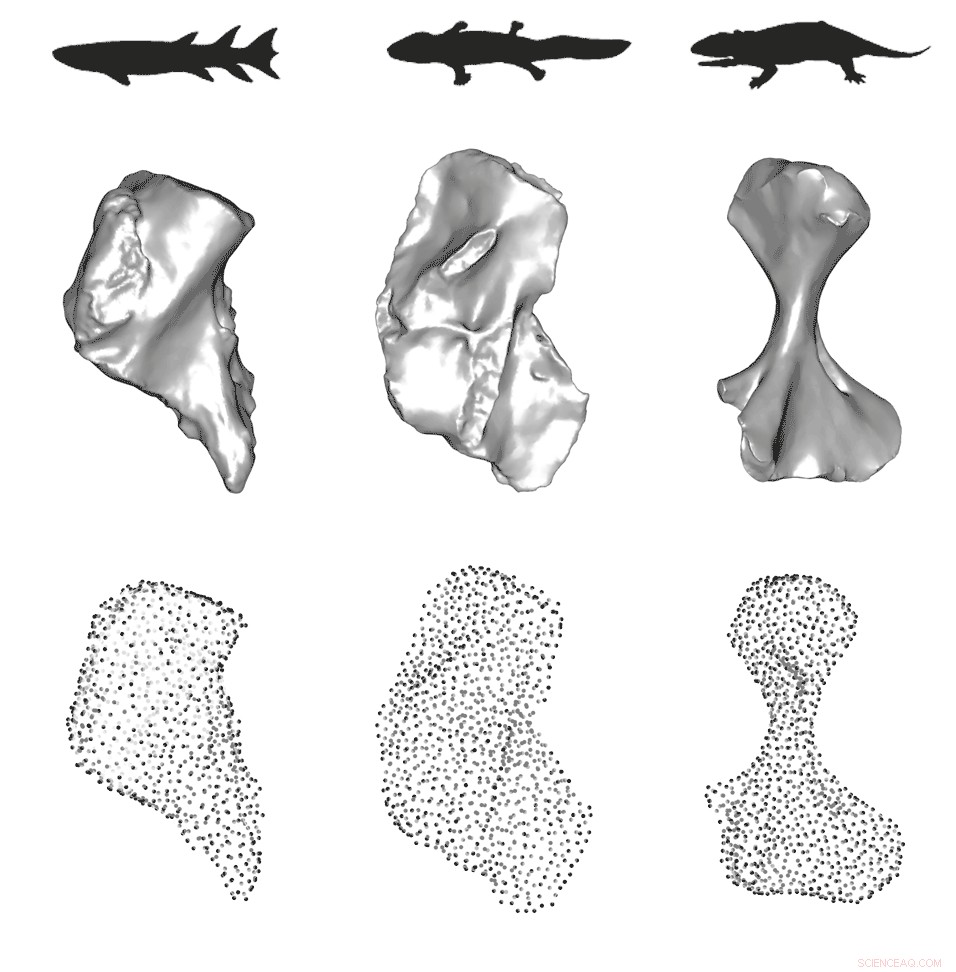

Tre fasi principali dell'evoluzione della forma dell'omero:dall'omero a blocchi dei pesci acquatici, all'omero a forma di L dei tetrapodi di transizione, e l'omero ritorto dei tetrapodi terrestri. Colonne (da sinistra a destra) =pesce acquatico, tetrapodi di transizione, e tetrapodi terrestri. Righe =In alto:sagome di animali estinti; Al centro:fossili di omero 3D; In basso:punti di riferimento utilizzati per quantificare la forma. Credito:Blake Dickson

La transizione acqua-terra è una delle più importanti e stimolanti transizioni nell'evoluzione dei vertebrati. E la questione di come e quando i tetrapodi sono passati dall'acqua alla terra è stata a lungo fonte di meraviglia e dibattito scientifico.

Le prime idee ipotizzavano che il prosciugamento delle pozze d'acqua di pesci spiaggiati a terra e che l'essere fuori dall'acqua fornisse la pressione selettiva per evolvere più appendici simili a arti per tornare all'acqua. Negli anni '90, gli esemplari scoperti di recente hanno suggerito che i primi tetrapodi conservassero molte caratteristiche acquatiche, come branchie e una pinna caudale, e che gli arti possono essersi evoluti nell'acqua prima che i tetrapodi si adattassero alla vita sulla terra. C'è, però, ancora incertezza su quando avvenne la transizione acqua-terra e su come fossero realmente i primi tetrapodi terrestri.

Un articolo pubblicato il 25 novembre in Natura affronta queste domande utilizzando dati fossili ad alta risoluzione e mostra che sebbene questi primi tetrapodi fossero ancora legati all'acqua e avessero caratteristiche acquatiche, avevano anche adattamenti che indicano una certa capacità di muoversi sulla terraferma. Sebbene, potrebbero non essere stati molto bravi a farlo, almeno per gli standard odierni.

L'autore principale Blake Dickson, dottorato di ricerca '20 presso il Dipartimento di Biologia Organismica ed Evoluzionistica dell'Università di Harvard, e l'autrice senior Stephanie Pierce, Thomas D. Cabot Professore Associato nel Dipartimento di Biologia Organismica ed Evoluzionistica e curatore di paleontologia dei vertebrati nel Museo di Zoologia Comparata dell'Università di Harvard, ha esaminato 40 modelli tridimensionali di omeri fossili (osso del braccio) di animali estinti che collegano la transizione acqua-terra.

"Poiché la documentazione fossile della transizione verso la terra nei tetrapodi è così scarsa, siamo andati a una fonte di fossili che potrebbe rappresentare meglio l'intera transizione dall'essere un pesce completamente acquatico a un tetrapode completamente terrestre, " disse Dickson.

Due terzi dei fossili provenivano dalle collezioni storiche conservate presso il Museum of Comparative Zoology di Harvard, che provengono da tutto il mondo. Per colmare le lacune mancanti, Pierce ha contattato i colleghi con campioni chiave dal Canada, Scozia, e Australia. Di importanza per lo studio sono stati i nuovi fossili scoperti di recente dai coautori Dr. Tim Smithson e Professor Jennifer Clack, Università di Cambridge, UK, nell'ambito del progetto TW:eed, un'iniziativa progettata per comprendere la prima evoluzione dei tetrapodi terrestri.

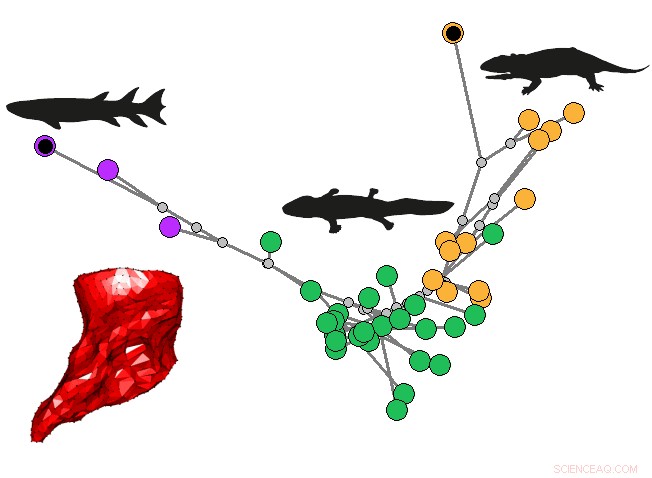

Il percorso evolutivo e la forma cambiano da un omero di pesce acquatico a un omero tetrapode terrestre. Credito:Blake Dickson.

I ricercatori hanno scelto l'osso dell'omero perché non solo è abbondante e ben conservato nei reperti fossili, ma è presente anche in tutti i sarcopterigi, un gruppo di animali che comprende pesci celacanto, pesce polmonato, e tutti i tetrapodi, compresi tutti i loro rappresentanti fossili. "Ci aspettavamo che l'omero avrebbe portato un forte segnale funzionale mentre gli animali passavano dall'essere un pesce perfettamente funzionante a essere tetrapodi completamente terrestri, e che potremmo usarlo per prevedere quando i tetrapodi hanno iniziato a muoversi sulla terraferma, " disse Pierce. "Abbiamo scoperto che l'abilità terrestre sembra coincidere con l'origine degli arti, che è davvero emozionante."

L'omero ancora la gamba anteriore al corpo, ospita molti muscoli, e deve resistere a molto stress durante il movimento basato sugli arti. A causa di ciò, contiene una grande quantità di informazioni funzionali critiche relative al movimento e all'ecologia di un animale. Researchers have suggested that evolutionary changes in the shape of the humerus bone, from short and squat in fish to more elongate and featured in tetrapods, had important functional implications related to the transition to land locomotion. This idea has rarely been investigated from a quantitative perspective—that is, until now.

When Dickson was a second-year graduate student, he became fascinated with applying the theory of quantitative trait modeling to understanding functional evolution, a technique pioneered in a 2016 study led by a team of paleontologists and co-authored by Pierce. Central to quantitative trait modeling is paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson's 1944 concept of the adaptive landscape, a rugged three-dimensional surface with peaks and valleys, like a mountain range. On this landscape, increasing height represents better functional performance and adaptive fitness, and over time it is expected that natural selection will drive populations uphill towards an adaptive peak.

Dickson and Pierce thought they could use this approach to model the tetrapod transition from water to land. They hypothesized that as the humerus changed shape, the adaptive landscape would change too. Ad esempio, fish would have an adaptive peak where functional performance was maximized for swimming and terrestrial tetrapods would have an adaptive peak where functional performance was maximized for walking on land. "We could then use these landscapes to see if the humerus shape of earlier tetrapods was better adapted for performing in water or on land" said Pierce.

"We started to think about what functional traits would be important to glean from the humerus, " said Dickson. "Which wasn't an easy task as fish fins are very different from tetrapod limbs." In the end, they narrowed their focus on six traits that could be reliably measured on all of the fossils including simple measurements like the relative length of the bone as a proxy for stride length and more sophisticated analyses that simulated mechanical stress under different weight bearing scenarios to estimate humerus strength.

"If you have an equal representation of all the functional traits you can map out how the performance changes as you go from one adaptive peak to another, " Dickson explained. Using computational optimization the team was able to reveal the exact combination of functional traits that maximized performance for aquatic fish, terrestrial tetrapods, and the earliest tetrapods. Their results showed that the earliest tetrapods had a unique combination of functional traits, but did not conform to their own adaptive peak.

"What we found was that the humeri of the earliest tetrapods clustered at the base of the terrestrial landscape, " said Pierce. "indicating increasing performance for moving on land. But these animals had only evolved a limited set of functional traits for effective terrestrial walking."

The researchers suggest that the ability to move on land may have been limited due to selection on other traits, like feeding in water, that tied early tetrapods to their ancestral aquatic habitat. Once tetrapods broke free of this constraint, the humerus was free to evolve morphologies and functions that enhanced limb-based locomotion and the eventual invasion of terrestrial ecosystems

"Our study provides the first quantitative, high-resolution insight into the evolution of terrestrial locomotion across the water-land transition, " said Dickson. "It also provides a prediction of when and how [the transition] happened and what functions were important in the transition, at least in the humerus."

"Andando avanti, we are interested in extending our research to other parts of the tetrapod skeleton, " Pierce said. "For instance, it has been suggested that the forelimbs became terrestrially capable before the hindlimbs and our novel methodology can be used to help test that hypothesis."

Dickson recently started as a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Animal Locomotion lab at Duke University, but continues to collaborate with Pierce and her lab members on further studies involving the use of these methods on other parts of the skeleton and fossil record.