Il presidente degli Stati Uniti Donald Trump ha fatto false affermazioni sulla diffusa frode elettorale durante le elezioni presidenziali del 2020. I ricercatori di UNSW Psychology hanno ora trovato un modo per non essere ingannati con le cosiddette "notizie false" da un'unica fonte. Credito:Shutterstock

Se più persone ti dicessero che qualcosa è vero, penseresti che tenderesti a crederci.

Non secondo uno studio del 2019 della Yale University che ha scoperto che le persone credono a un'unica fonte di informazioni che si ripete attraverso molti canali (un "falso consenso"), proprio come più persone dicono loro qualcosa sulla base di molte fonti originali indipendenti (un 'vero consenso').

La scoperta ha mostrato come la disinformazione può essere rafforzata e ha avuto conseguenze per decisioni importanti che prendiamo sulla base dei consigli che riceviamo da luoghi come i governi e i media su informazioni come vaccinazioni, indossare maschere durante la pandemia o persino per chi votiamo in un'elezione .

La scoperta dell'"illusione del consenso" del 2019 ha affascinato il ricercatore post-dottorato della School of Psychology dell'UNSW Science, Saoirse Connor Desai, che ha testato la scoperta dell'illusione e ha trovato un modo per evitare che le persone vengano ingannate con le cosiddette "notizie false" da un unica fonte.

Lo studio del suo team è stato pubblicato su Cognition .

"Abbiamo scoperto che l'illusione può essere ridotta quando forniamo alle persone informazioni su come le fonti originali hanno utilizzato le prove per arrivare alle loro conclusioni", afferma il dottor Connor Desai.

Dice che la scoperta è particolarmente rilevante per le migliori pratiche di comunicazione scientifica, ad es. in che modo i responsabili politici o i media presentano alle persone prove o ricerche scientifiche esperte.

Ad esempio, oltre l'80% dei blog che negano il cambiamento climatico ripetono affermazioni di una sola persona che afferma di essere un "esperto di orso polare".

"Potresti avere una situazione in cui una proposta sanitaria fuorviante viene ripetuta attraverso più canali, il che potrebbe influenzare le persone a fare affidamento su tali informazioni più di quanto dovrebbero, perché pensano che ci siano prove a sostegno o pensano che ci sia un consenso", dice il dottor Connor Desai.

"Ma la nostra scoperta mostra che se riesci a spiegare alle persone da dove provengono le tue informazioni e come le fonti originali sono arrivate alle loro conclusioni, ciò rafforza la loro capacità di identificare un 'vero consenso'".

Il dottor Connor Desai afferma che la scoperta dello studio di Yale è stata sorprendente per lei, "perché sembrava essere un atto d'accusa alla capacità umana di distinguere tra vero consenso e falso consenso".

"Lo studio originale ha mostrato che le persone sono abitualmente pessime in questo. Ci sono state molte situazioni in cui non sono mai state in grado di distinguere tra il vero e il falso consenso", afferma.

"È problematico perché se le persone ascoltano le affermazioni false o fuorvianti di una singola persona ripetute attraverso canali diversi, potrebbero ritenere che l'affermazione sia più valida di quanto non sia."

Dr. Connor Desai says an example of this is multiple independent experts agreeing that Ivermectin should not be used to treat COVID-19 (true consensus), versus a single group or individual saying that people should use it as an anti-viral drug (false consensus).

How the study was conducted

The aim of the UNSW study was to understand why people believe false information when it's repeated.

"Our main goal was to establish whether one reason that people are equally convinced by true and false consensus is that they assume that different sources share data or methodologies," Dr. Connor Desai says.

"Do they understand there is potentially more evidence when you have multiple experts saying the same thing?"

The UNSW researchers conducted several experiments.

The first experiment replicated the 2019 Yale study, which saw participants given a variety of articles about a fictional tax policy which took positive, negative, or neutral stances, and then asked to what extent they agreed the proposal would improve the economy.

It replicated the "illusion of consensus" where people are equally convinced by one piece of evidence as they are by many pieces of evidence but added a new condition where they told people who saw a "true consensus" that the sources had used different data and methods to arrive at their conclusions.

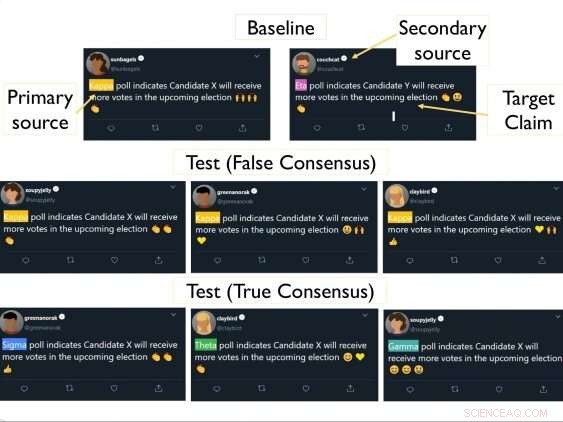

An example of the made up Twitter posts used in the study.

The result was a reduction in the illusion of consensus.

"People were more convinced by true consensus than false consensus."

In another experiment, 200 participants were given information about an election in a fictional foreign democratic country.

They were shown fictional Twitter posts from news outlets that said which candidates would get more votes in the election:some sourced the same or different pollsters to predict a candidate would win, while another tweet said a different contender would win.

But in the true consensus Twitter posts, they gave people a scenario in which it was clear that different primary sources worked independently and used different data to arrive at their conclusions.

"We expected that many people would be more familiar with such polls and would realize that looking at multiple different polls would be a better way of predicting the election result than just seeing a single poll multiple times," Dr. Connor Desai says.

After reading the tweets, participants rated which candidate would win based on the polling predictions.

"It seemed that people were more convinced by a true consensus than a false consensus when they understood the pollsters had gathered evidence independently of one another," Professor of Cognitive Psychology in the School of Psychology, Brett Hayes says.

"Our results suggest that people do see claims endorsed by multiple sources as stronger when they believe these sources really are independent of one another."

The researchers later replicated and extended the tweet study with 365 more participants.

"This time we had a condition where the tweets came from individual people who showed their endorsement of the polls using emojis," Dr. Connor Desai says.

"Regardless of whether the tweets came from news outlets, or individual tweeters, people were more convinced by true than false consensus when the relationship between sources was unambiguous."

False consensus not completely discounted

But the researchers also found the participants didn't completely discount false consensus.

"There are at least two possible explanations for this effect," Dr. Connor Desai said.

"The first is that such repetition simply increases the familiarity of the claim—enhancing its memory representation, and this is sufficient to increase confidence.

"The second is that people may make inferences about why a claim is repeated because the source believed it was the most reputable or provided the strongest evidence.

"For instance, if different news channels all cite the same expert you might think that they're citing the same person because they are the most qualified to talk about whatever it is they're talking about."

Dr. Connor Desai plans to next look at why some communication strategies are more effective than others, and if repeating information is always effective.

"Is there a point where there's too much consensus, and people become suspicious?" she says.

"Can you correct a 'false consensus' by pointing out that it's often better to get information from multiple independent sources? These are the kinds of strategies we wish to look into."