Joshi Festival nella tribù Kalash in Pakistan, 14 maggio 2011. Credit:Shutterstock/Maharani afifah

Apro gli occhi al suono di una voce mentre l'aereo a elica bimotore della Pakistan Airlines vola attraverso la catena montuosa dell'Hindu Kush, a ovest del possente Himalaya. Stiamo navigando a 27.000 piedi, ma le montagne intorno a noi sembrano preoccupantemente vicine e la turbolenza mi ha svegliato durante un viaggio di 22 ore nel luogo più remoto del Pakistan:le valli Kalash della regione di Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa.

Alla mia sinistra, una passeggera sconvolta sta pregando in silenzio. Alla mia immediata destra siede la mia guida, traduttrice e amico Taleem Khan, un membro della tribù politeista Kalash che conta circa 3.500 persone. Questo era l'uomo che mi stava parlando mentre mi stavo svegliando. Si china di nuovo e chiede, questa volta in inglese:"Buongiorno, fratello. Stai bene?"

"Prúst," (sto bene) rispondo, mentre divento più consapevole di ciò che mi circonda.

Non sembra che l'aereo stia discendendo; piuttosto, sembra che il terreno ci venga incontro. E dopo che l'aereo ha colpito la pista e i passeggeri sono sbarcati, il capo della stazione di polizia di Chitral è lì per salutarci. Ci viene assegnata una scorta di polizia per la nostra protezione (quattro agenti che operano su due turni), poiché in questa parte del mondo ci sono minacce molto reali per ricercatori e giornalisti.

Solo allora possiamo intraprendere la seconda tappa del nostro viaggio:un giro in jeep di due ore verso le valli del Kalash su una strada sterrata che ha alte montagne da un lato e un dislivello di 200 piedi nel fiume Bumburet dall'altro. I colori intensi e la vivacità della location vanno vissuti per essere compresi.

L'obiettivo di questo viaggio di ricerca, condotto dal Durham University Music and Science Lab, è scoprire come la percezione emotiva della musica possa essere influenzata dal background culturale degli ascoltatori ed esaminare se ci sono aspetti universali delle emozioni trasmesse dalla musica . Per aiutarci a capire questa domanda, volevamo trovare persone che non fossero state esposte alla cultura occidentale.

I villaggi che saranno la nostra base operativa sono sparsi in tre valli al confine tra il nord-ovest del Pakistan e l'Afghanistan. Ospitano un certo numero di tribù, sebbene sia a livello nazionale che internazionale siano conosciute come le valli Kalash (dal nome della tribù Kalash). Nonostante la loro popolazione relativamente piccola, i loro costumi unici, la religione politeista, i rituali e la musica li distinguono dai loro vicini.

La strada da Chitral alla valle centrale di Kalash. Credito:George Athanasopoulos, autore fornito

Nel campo

Ho condotto ricerche in località come Papua Nuova Guinea, Giappone e Grecia. La verità è che il lavoro sul campo è spesso costoso, potenzialmente pericoloso e talvolta anche pericoloso per la vita.

Ma per quanto sia difficile condurre esperimenti di fronte a barriere linguistiche e culturali, la mancanza di una fornitura elettrica stabile per caricare le nostre batterie sarebbe uno degli ostacoli più difficili da superare in questo viaggio. I dati possono essere raccolti solo con l'assistenza e la disponibilità della popolazione locale. Le persone che abbiamo incontrato hanno letteralmente fatto il possibile per noi (in realtà, 16 miglia in più) in modo da poter ricaricare la nostra attrezzatura nella città più vicina con l'energia. Ci sono poche infrastrutture in questa regione del Pakistan. La centrale idroelettrica locale fornisce 200 W per ogni famiglia di notte, ma è soggetta a malfunzionamenti a causa di relitti dopo ogni pioggia, causandone l'interruzione del funzionamento ogni due giorni.

Una volta superati i problemi tecnici, eravamo pronti per iniziare la nostra indagine musicale. Quando ascoltiamo la musica, dipendiamo fortemente dalla nostra memoria della musica che abbiamo ascoltato nel corso della nostra vita. Le persone in tutto il mondo usano diversi tipi di musica per scopi diversi. E le culture hanno i loro modi consolidati di esprimere temi ed emozioni attraverso la musica, così come hanno sviluppato preferenze per determinate armonie musicali. Le tradizioni culturali modellano quali armonie musicali trasmettono felicità e, fino a un certo punto, quanta dissonanza armonica viene apprezzata. Pensa, ad esempio, all'umore felice di Here Comes the Sun dei Beatles e confrontalo con l'infausta durezza della colonna sonora di Bernard Herrmann per la famigerata scena della doccia in Psycho di Hitchcock.

Quindi, poiché la nostra ricerca mirava a scoprire come la percezione emotiva della musica può essere influenzata dal background culturale degli ascoltatori, il nostro primo obiettivo era individuare i partecipanti che non fossero esposti in modo schiacciante alla musica occidentale. Questo è più facile a dirsi che a farsi, a causa dell'effetto generale della globalizzazione e dell'influenza che gli stili musicali occidentali hanno sulla cultura mondiale. Un buon punto di partenza è stato cercare luoghi privi di una stabile fornitura di elettricità e di pochissime stazioni radio. Ciò di solito significherebbe una connessione Internet scarsa o assente con accesso limitato alle piattaforme musicali online o, in effetti, qualsiasi altro mezzo per accedere alla musica globale.

Uno dei vantaggi della nostra posizione prescelta era che la cultura circostante non era orientata all'occidente, ma piuttosto in una sfera culturale completamente diversa. La cultura punjabi è la corrente principale in Pakistan, poiché i punjabi sono il gruppo etnico più numeroso. Ma la cultura Khowari domina nelle valli di Kalash. Meno del 2% parla l'urdu, la lingua franca del Pakistan, come lingua madre. Il popolo Kho (una tribù vicina ai Kalash), conta circa 300.000 persone e faceva parte del Regno di Chitral, uno stato principesco che fece parte prima del Raj britannico, e poi della Repubblica islamica del Pakistan fino al 1969. Il mondo occidentale è visto dalle comunità lì come qualcosa di "diverso", "estraneo" e "non nostro".

Il secondo obiettivo era individuare le persone la cui musica consiste in una tradizione esecutiva consolidata e autoctona in cui l'espressione delle emozioni attraverso la musica è eseguita in modo paragonabile a quello occidentale. Questo perché, anche se stavamo cercando di sfuggire all'influenza della musica occidentale sulle pratiche musicali locali, era comunque importante che i nostri partecipanti capissero che la musica potrebbe potenzialmente trasmettere emozioni diverse.

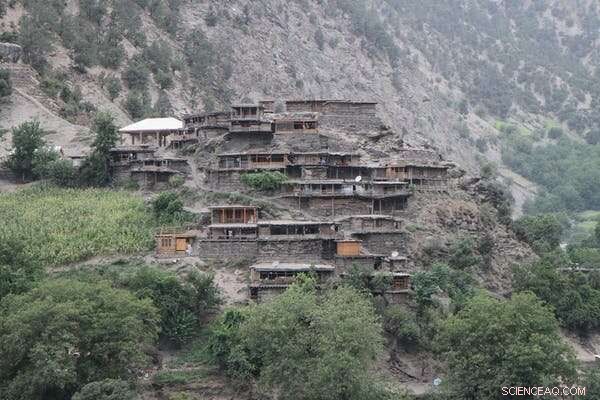

Abitazioni in legno nella valle del Rumbur, una delle tre valli abitate dal popolo Kalash nel distretto di Chitral, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Credito:Shutterstock/knovakov

Infine, avevamo bisogno di un luogo in cui le nostre domande potessero essere poste in un modo che consentisse a partecipanti di culture diverse di valutare l'espressione emotiva nella musica sia occidentale che non occidentale.

Per i Kalash, la musica non è un passatempo; è un identificatore culturale. È un aspetto inseparabile della pratica sia rituale che non rituale, della nascita e della vita. When someone dies, they are sent off to the sounds of music and dancing, as their life story and deeds are retold.

Meanwhile, the Kho people view music as one of the "polite" and refined arts. They use it to highlight the best aspects of their poetry. Their evening gatherings, typically held after dark in the homes of prominent members of the community, are comparable to salon gatherings in Enlightenment Europe, in which music, poetry and even the nature of the act and experience of thought are discussed. I was often left to marvel at how regularly men, who seemingly could bend steel with their piercing gaze, were moved to tears by a simple melody, a verse, or the silence which followed when a particular piece of music had just ended.

It was also important to find people who understood the concept of harmonic consonance and dissonance—that is, the relative attractiveness and unattractiveness of harmonies. This is something which can be easily done by observing whether local musical practices include multiple, simultaneous voices singing together one or more melodic lines. After running our experiments with British participants, we came to the Kalash and Kho communities to see how non-western populations perceive these same harmonies.

Our task was simple:expose our participants from these remote tribes to voice and music recordings which varied in emotional intensity and context, as well as some artificial music samples we had put together.

Major and minor

A mode is the language or vocabulary that a piece of music is written in, while a chord is a set of pitches which sound together. The two most common modes in western music are major and minor. Here Comes the Sun by The Beatles is a song in a major scale, using only major chords, while Call Out My Name by the Weeknd is a song in a minor scale, which uses only minor chords. In western music, the major scale is usually associated with joy and happiness, while the minor scale is often associated with sadness.

Right away we found that people from the two tribes were reacting to major and minor modes in a completely different manner to our UK participants. Our voice recordings, in Urdu and German (a language very few here would be familiar with), were perfectly understood in terms of their emotional context and were rated accordingly. But it was less than clear cut when we started introducing the musical stimuli, as major and minor chords did not seem to get the same type of emotional reaction from the tribes in northwest Pakistan as they do in the west.

We began by playing them music from their own culture and asked them to rate it in terms of its emotional context; a task which they performed excellently. Then we exposed them to music which they had never heard before, ranging from West Coast Jazz and classical music to Moroccan Tuareg music and Eurovision pop songs.

While commonalities certainly exist—after all, no army marches to war singing softly, and no parent screams their children to sleep—the differences were astounding. How could it be that Rossini's humorous comic operas, which have been bringing laughter and joy to western audiences for almost 200 years, were seen by our Kho and Kalash participants to convey less happiness than 1980s speed metal?

We were always aware that the information our participants provided us with had to be placed in context. We needed to get an insider perspective on their train of thought regarding the perceived emotions.

Essentially, we were trying to understand the reasons behind their choices and ratings. After countless repetitions of our experiments and procedures and making sure that our participants had understood the tasks that we were asking them to do, the possibility started to emerge that they simply did not prefer the consonance of the most common western harmonies.

Not only that, but they would go so far as to dismiss it as sounding "foreign." Indeed, a recurring trope when responding to the major chord was that it was "strange" and "unnatural," like "European music." That it was "not our music."

What is natural and what is cultural?

Once back from the field, our research team met up and together with my colleagues Dr. Imre Lahdelma and Professor Tuomas Eerola we started interpreting the data and double checking the preliminary results by putting them through extensive quality checks and number crunching with rigorous statistical tests. Our report on the perception of single chords shows how the Khalash and Kho tribes perceived the major chord as unpleasant and negative, and the minor chord as pleasant and positive.

To our astonishment, the only thing the western and the non-western responses had in common was the universal aversion to highly dissonant chords. The finding of a lack of preference for consonant harmonies is in line with previous cross-cultural research investigating how consonance and dissonance are perceived among the Tsimané, an indigenous population living in the Amazon rainforest of Bolivia with limited exposure to western culture. Notably, however, the experiment conducted on the Tsimané did not include highly dissonant harmonies in the stimuli. So the study's conclusion of an indifference to both consonance and dissonance might have been premature in the light of our own findings.

When it comes to emotional perception in music, it is apparent that a large amount of human emotions can be communicated across cultures at least on a basic level of recognition. Listeners who are familiar with a specific musical culture have a clear advantage over those unfamiliar with it—especially when it comes to understanding the emotional connotations of the music.

But our results demonstrated that the harmonic background of a melody also plays a very important role in how it is emotionally perceived. See, for example, Victor Borge's Beethoven variation on the melody of Happy Birthday, which on its own is associated with joy, but when the harmonic background and mode changes the piece is given an entirely different mood.

Then there is something we call "acoustic roughness," which also seems to play an important role in harmony perception—even across cultures. Roughness denotes the sound quality that arises when musical pitches are so close together that the ear cannot fully resolve them. This unpleasant sound sensation is what Bernard Herrmann so masterfully uses in the aforementioned shower scene in Psycho. This acoustic roughness phenomenon has a biologically determined cause in how the inner ear functions and its perception is likely to be common to all humans.

According to our findings, harmonisations of melodies that are high in roughness are perceived to convey more energy and dominance—even when listeners have never heard similar music before. This attribute has an affect on how music is emotionally perceived, particularly when listeners lack any western associations between specific music genres and their connotations.

For example, the Bach chorale harmonization in major mode of the simple melody below was perceived as conveying happiness only to our British participants. Our Kalash and Kho participants did not perceive this particular style to convey happiness to a greater degree than other harmonisations.

The wholetone harmonization below, on the other hand, was perceived by all listeners—western and non-western alike—to be highly energetic and dominant in relation to the other styles. Energy, in this context, refers to how music may be perceived to be active and "awake," while dominance relates to how powerful and imposing a piece of music is perceived to be.

Carl Orff's O Fortuna is a good example of a highly energetic and dominant piece of music for a western listener, while a soft lullaby by Johannes Brahms would not be ranked high in terms of dominance or energy. At the same time, we noted that anger correlated particularly well with high levels of roughness across all groups and for all types of real (for example, the Heavy Metal stimuli we used) or artificial music (such as the wholetone harmonization below) that the participants were exposed to.

So, our results show both with single, isolated chords and with longer harmonisations that the preference for consonance and the major-happy, minor-sad distinction seems to be culturally dependent. These results are striking in the light of tradition handed down from generation to generation in music theory and research. Western music theory has assumed that because we perceive certain harmonies as pleasant or cheerful this mode of perception must be governed by some universal law of nature, and this line of thinking persists even in contemporary scholarship.

Indeed, the prominent 18th century music theorist and composer Jean-Philippe Rameau advocated that the major chord is the "perfect" chord, while the later music theorist and critic Heinrich Schenker concluded that the major is "natural" as opposed to the "artificial" minor.

But years of research evidence now shows that it is safe to assume that the previous conclusions of the "naturalness" of harmony perception were uninformed assumptions, and failed even to attempt to take into account how non-western populations perceive western music and harmony.

Just as in language we have letters that build up words and sentences, so in music we have modes. The mode is the vocabulary of a particular melody. One erroneous assumption is that music consists of only the major and minor mode, as these are largely prevalent in western mainstream pop music.

In the music of the region where we conducted our research, there are a number of different, additional modes which provide a wide range of shades and grades of emotion, whose connotation may change not only by core musical parameters such as tempo or loudness, but also by a variety of extra-musical parameters (performance setting, identity, age and gender of the musicians).

For example, a video of the late Dr. Lloyd Miller playing a piano tuned in the Persian Segah dastgah mode shows how so many other modes are available to express emotion. The major and minor mode conventions that we consider as established in western tonal music are but one possibility in a specific cultural framework. They are not a universal norm.

Why is this important?

Research has the potential to uncover how we live and interact with music, and what it does to us and for us. It is one of the elements that makes the human experience more whole. Whatever exceptions exist, they are enforced and not spontaneous, and music, in some form, is present in all human cultures. The more we investigate music around the world and how it affects people, the more we learn about ourselves as a species and what makes us feel .

Our findings provide insights, not only into intriguing cultural variations regarding how music is perceived across cultures, but also how we respond to music from cultures which are not our own. Can we not appreciate the beauty of a melody from a different culture, even if we are ignorant to the meaning of its lyrics? There are more things that connect us through music than set us apart.

When it comes to musical practices, cultural norms can appear strange when viewed from an outsider's perspective. For example, we observed a Kalash funeral where there was lots of fast-paced music and highly-energetic dancing. A western listener might wonder how it is possible to dance with such vivacity to music which is fast, rough and atonal—at a funeral.

But at the same time, a Kalash observer might marvel at the sombreness and quietness of a western funeral:was the deceased a person of so little importance that no sacrifices, honorary poems, praise songs and loud music and dancing were performed in their memory? As we assess the data captured in the field a world away from our own, we become more aware of the way music shapes the stories of the people who make it, and how it is shaped by culture itself.

After we had said our goodbyes to our Kalash and Kho hosts, we boarded a truck, drove over the dangerous Lowari Pass from Chitral to Dir, and then traveled to Islamabad and on to Europe. And throughout the trip, I had the words of a Khowari song in my mind:"The old path, I burn it, it is warm like my hands. In the young world, you will find me."