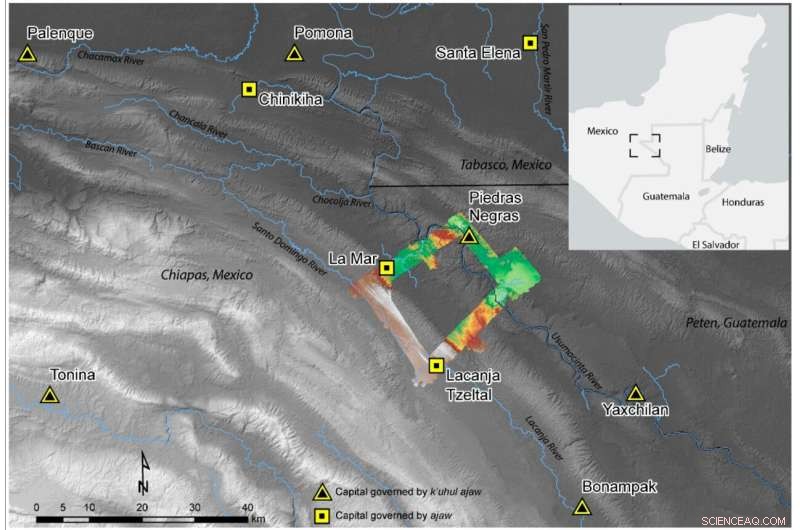

Il team di ricerca ha esaminato una piccola area nelle pianure Maya occidentali situata all'odierno confine tra Messico e Guatemala, mostrata nel contesto qui. Credito:Andrew Scherer/Brown University

Molti credono che il cambiamento climatico e il degrado ambientale abbiano causato la caduta della civiltà Maya, ma una nuova indagine mostra che alcuni regni Maya avevano pratiche agricole sostenibili e rese alimentari elevate per secoli.

Per anni, esperti in scienze del clima ed ecologia hanno sostenuto le pratiche agricole degli antichi Maya come ottimi esempi di cosa non fare.

"C'è una narrazione che descrive i Maya come persone impegnate in uno sviluppo agricolo incontrollato", ha affermato Andrew Scherer, professore associato di antropologia alla Brown University. "La narrazione dice:la popolazione è cresciuta troppo, l'agricoltura è aumentata e poi tutto è andato in pezzi".

Ma un nuovo studio, scritto da Scherer, studenti della Brown e studiosi di altre istituzioni, suggerisce che quella narrazione non racconta tutta la storia.

Utilizzando droni e lidar, una tecnologia di telerilevamento, un team guidato da Scherer e Charles Golden della Brandeis University ha esaminato una piccola area nelle pianure Maya occidentali situata all'odierno confine tra Messico e Guatemala. L'indagine lidar di Scherer - e, in seguito, il rilevamento con gli stivali sul terreno - hanno rivelato estesi sistemi di irrigazione sofisticata e terrazzamenti all'interno e all'esterno delle città della regione, ma nessun enorme boom demografico all'altezza. I risultati dimostrano che tra il 350 e il 900 d.C., alcuni regni Maya vivevano comodamente, con sistemi agricoli sostenibili e senza dimostrata insicurezza alimentare.

"È emozionante parlare delle popolazioni davvero numerose che i Maya mantenevano in alcuni luoghi; sopravvivere così a lungo con una tale densità è stata una testimonianza dei loro risultati tecnologici", ha detto Scherer. "Ma è importante capire che quella narrazione non si traduce in tutta la regione Maya. Le persone non sono sempre state in vita. Alcune aree che avevano un potenziale di sviluppo agricolo non sono mai state nemmeno occupate".

I risultati del gruppo di ricerca sono stati pubblicati sulla rivista Remote Sensing .

Quando il team di Scherer ha intrapreso l'indagine sul lidar, non stava necessariamente tentando di sfatare le ipotesi di lunga data sulle pratiche agricole Maya. Piuttosto, la loro motivazione principale era quella di saperne di più sulle infrastrutture di una regione relativamente poco studiata. Mentre alcune parti dell'area Maya occidentale sono ben studiate, come il famoso sito di Palenque, altre sono meno conosciute, a causa della fitta chioma tropicale che ha nascosto a lungo antiche comunità alla vista. È stato solo nel 2019, infatti, che Scherer e colleghi hanno scoperto il regno di Sak T'zi", che gli archeologi stavano cercando di trovare per decenni.

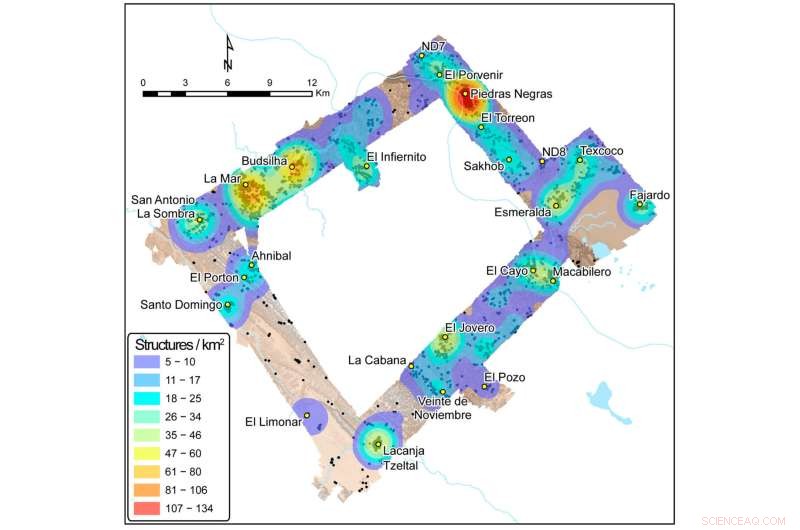

Le scansioni Lidar dell'area di ricerca hanno rivelato la densità relativa delle strutture a Piedras Negras, La Mar e Lacanjá Tzeltal, fornendo suggerimenti sulle rispettive popolazioni e sui bisogni alimentari di queste città. Credito:Brown University

Il team ha scelto di esaminare un rettangolo di terra che collega tre regni Maya:Piedras Negras, La Mar e Sak Tz'i", la cui capitale politica era centrata sul sito archeologico di Lacanjá Tzeltal. Nonostante fosse a circa 15 miglia di distanza l'uno dall'altro come il in linea d'aria, questi tre centri urbani avevano dimensioni della popolazione e potere di governo molto diversi, ha affermato Scherer.

"Oggi, il mondo ha centinaia di stati-nazione diversi, ma non sono davvero uguali l'uno all'altro in termini di influenza che hanno nel panorama geopolitico", ha detto Scherer. "This is what we see in the Maya empire as well."

Scherer explained that all three kingdoms were governed by an ajaw, or a lord—positioning them as equals, in theory. But Piedras Negras, the largest kingdom, was led by a k'uhul ajaw, a "holy lord," a special honorific not claimed by the lords of La Mar and Sak Tz'i." La Mar and Sak Tz'i' weren't exactly equal peers, either:While La Mar was much more populous than the Sak T'zi' capital Lacanjá Tzeltal, the latter was more independent, often switching alliances and never appearing to be subordinate to other kingdoms, suggesting it had greater political autonomy.

The lidar survey showed that despite their differences, these three kingdoms boasted one major similarity:Agriculture that yielded a food surplus.

"What we found in the lidar survey points to strategic thinking on the Maya's part in this area," Scherer said. "We saw evidence of long-term agricultural infrastructure in an area with relatively low population density—suggesting that they didn't create some crop fields late in the game as a last-ditch attempt to increase yields, but rather that they thought a few steps ahead."

In all three kingdoms, the lidar revealed signs of what the researchers call "agricultural intensification"—the modification of land to increase the volume and predictability of crop yields. Agricultural intensification methods in these Maya kingdoms, where the primary crop was maize, included building terraces and creating water management systems with dams and channeled fields. Penetrating through the often-dense jungle, the lidar showed evidence of extensive terracing and expansive irrigation channels across the region, suggesting that these kingdoms were not only prepared for population growth but also likely saw food surpluses every year.

"It suggests that by the late Classic Period, around 600 to 800 A.D., the area's farmers were producing more food than they were consuming," Scherer said. "It's likely that much of the surplus food was sold at urban marketplaces, both as produce and as part of prepared foods like tamales and gruel, and used to pay tribute, a tax of sorts, to local lords."

Scherer said he hopes the study provides scholars with a more nuanced view of the ancient Maya—and perhaps even offers inspiration for members of the modern-day agricultural sector who are looking for sustainable ways to grow food for an ever-growing global population. Today, he said, significant parts of the region are being cleared for cattle ranching and palm oil plantations. But in areas where people still raise corn and other crops, they report that they have three harvests a year—and it's likely that those high yields may be due in part to the channeling and other modifications that the ancient Maya made to the landscape.

"In conversations about contemporary climate or ecological crises, the Maya are often brought up as a cautionary tale:"They screwed up; we don't want to repeat their mistakes,'" Scherer said. "But maybe the Maya were more forward-thinking than we give them credit for. Our survey shows there's a good argument to be made that their agricultural practices were very much sustainable."